I have not been happy at work for a long time. My employer has refused to grant multiple holiday requests. I am not told why these are denied. I want time to go see my family. I am severely stressed and as a result have rising physical complaints.

Fatimah

I have an employment dispute

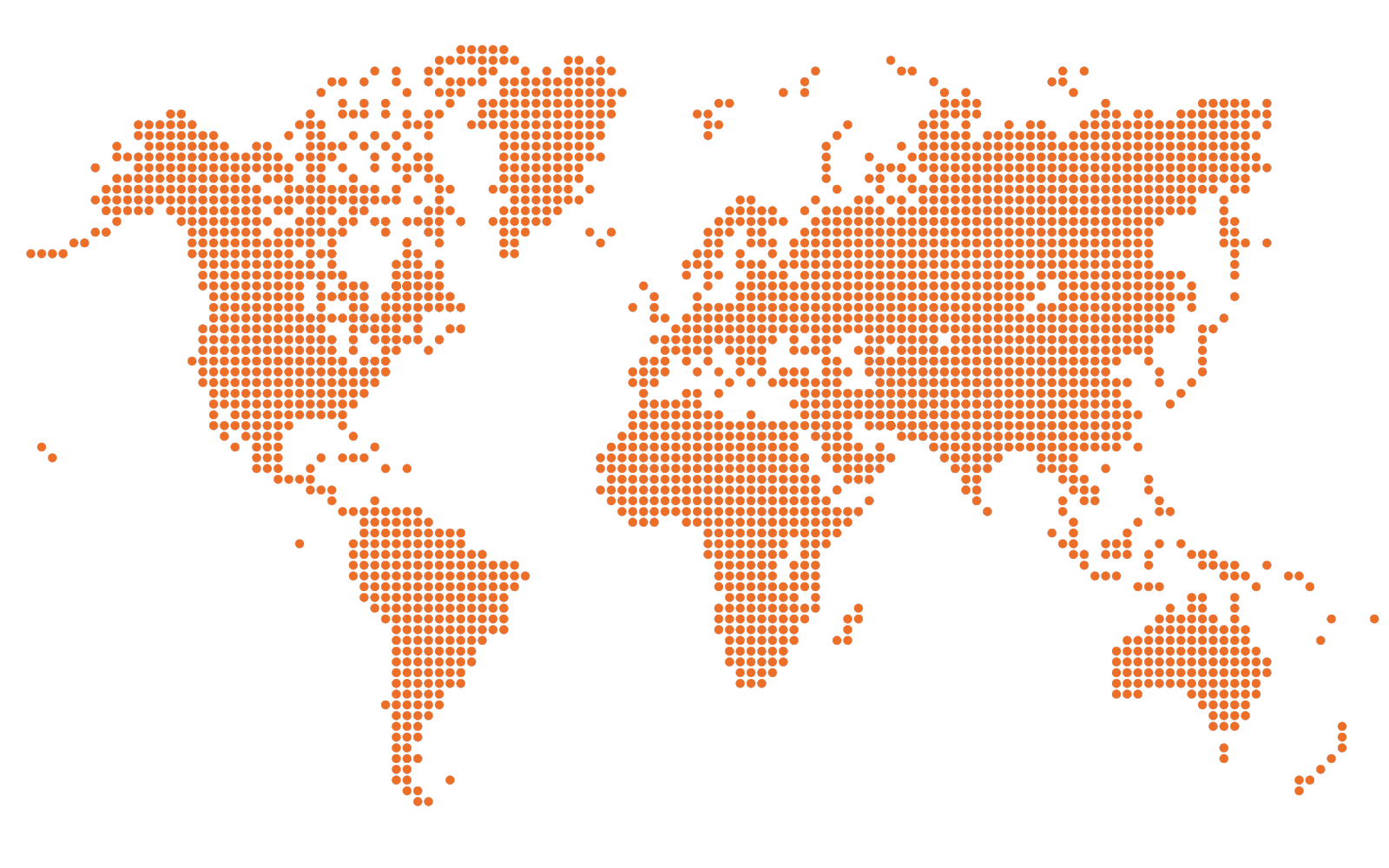

In

Nigeria 2.3M

people experience Employment related problems every year

Only

7%

of the

Employment

problems in

Tunesia

are completely resolved

One third of the people with

Employment

problems in

The Netherlands

found Courts and Lawyers as the most helpful mechanism.

Many suffer in silence against injustices. Fatimah is well within her rights to find a solution for the dispute at work. I would like to know how I can better help – before the plight escalates further.

Amir

I help people like Fatimah