Case study: Land Boundaries Dispute in Kenya

- Audience: HiiL experts, Data practice, Evidence-based work practice, Innovation Practice, JT practice

- Objective: exmplify a real-life example of one of the most frequently occurring legal problems

- Why is it important: JNS data shows that land and particularly boundary disputes is among the most frequent and pressing legal problems.

- What is the learning goal: set a very common legal problem in context and show how it affects people and why people-centred justice is important.

Images and video: Martin Gramatikov

Mike is an assistant county chief in a small rural community around 90 minutes from Nairobi, Kenya. I say “small”, but Mike’s constituency is around 20,000 people. He takes considerable pride that he knows his people, their families and histories. In his wordview, this intimate knowledge is key for being a community leader. Most of his concerns are that many of the young men in the community have lost their way under the influence of alcohol. Mike says, “In the village, even if you are 40, your mom will provide food and shelter.” A growing group of young men use this “social protection”, find odd jobs and mostly hang out around. At noon Mike and I saw a few guys hanging around, seemingly under the influence of alcohol.

A related concern of Mike is that many young women prefer to live alone with their kids instead of enduring erratic and/or abusive husbands. It is now seen as normal in the community for a young woman to expunge quickly a guy who is considered irresponsible. Mike believes that this is a better solution than the prospect of constant struggles, scandals, and, eventually domestic abuse.

Most people from the community are engaged in agriculture, working small plots scattered across the lush landscape. The soil is rich and fertile, offering promising prospects for the residents. According to Chief Mike, hard work, education, and persistence are needed for success in life.

The JNS studies often show that land disputes are the most frequent type of legal problem. During the interview, I asked Mike to tell me about a recent dispute in which he was engaged.

Mike immediately said that the previous day, he had to intervene in a land dispute and took me to a part of his community.

Small houses lined the rough red roads. The plots are relatively narrow – around 25-30 meters but as I discovered later, they are quite long – around 100-120 meters in length. A solid fence and a metal door separate the plots from the street. Behind the front face, however, there are no fences along the length of the plots. Narrow pathways divide the individual plots and serve as a footpath and a border. These pathways are essential for our story on land justice. It is difficult to resist the pun to call these narrow tracks “justice pathways” because of their role in disputes about land.

The house, which might consist of several adjacent buildings, is at the beginning of the plot. There might be a small backyard or an area for animals. The rest of the land is cultivated for different vegetables and crops. In the plot that I visited, there were sections with carrots, corn, beans, and other foodstufs. The owner of plot A called Chief Mike because she wanted to sell it. The lady inherited the plot from her grandfather and was suspicious that the border had shifted and her plot had become smaller. Mike advised the owners of the two plots to call a surveyor. The surveyor did his work shortly and showed where to put wooden polls to mark the true borders.

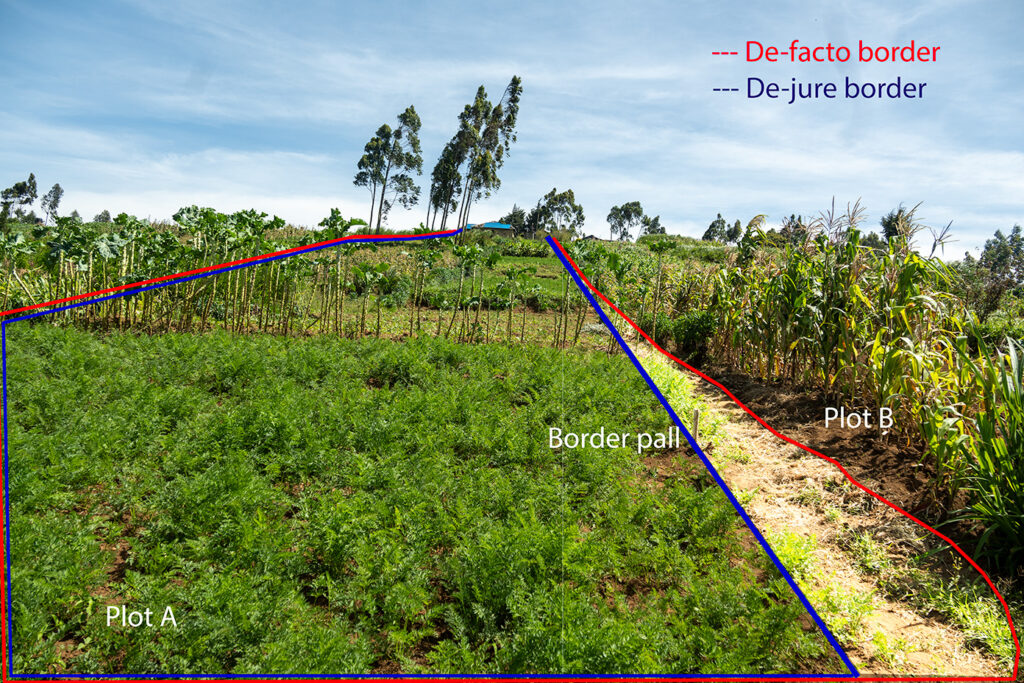

The wooden polls (called beakons in Kenya) clearly show that plot A has been “increased” at the expense of plot B. The picture below clearly shows a small triangle which has been “taken” from the plot B and “given” to plot A. According to Chief Mike, such “cases” happen all the time. He believes that most of the land disputes in his community are precisely of this type.

An important aspect of the story is that Chief Mike believes that such issues are not only frequent but they are often caused intentionally. He showed me how people push the boundaries by digging the vegetation that separates the plots. In the images below, he demonstrated how it works. There is a low hedge along the pathway. When you frequently push the plants to the left and dig out the roots, the plants move in the desired direction. This happens very slowly and the actual move happens over months or years. But it is a practice that can shape the boundaries of the land.

Chief Mike pointed out two other ways borders are occasionally “moved”. In the picture above, there are a couple of trees at the end of the plot. Sometimes plots of land are demarcated by trees. When the trees are cut, the boundaries become less clear and can be “adjusted”.

The other way is when rivers or creeks form the boundary. This is exactly the case of the two plots that I wrote about. River beds are fluid and can be altered.

Importance

Seemingly a very small patch of land has been appropriated. It has an economic value, although the economic gain from this patch is not so significant. Chief Mike and the owners of the two plots pointed out that it is not the lost or gained yield of the land but its emotional value. In agricultural societies, land has much more value than its economic worth. The land embodies the relationship to one’s family, community and ancestors. Both owners spoke of the importance of this land which they had inherited and is part of their identity. Another aspect of the emotional value is that one has to live in peace with his neighbours, who are often relatives. The presence of small injustices leaves the impression that big injustices are also possible. Rarely, but tragically, the small border “corrections” could lead to grim consequences.

People-centred justice practices and related lessons

Chief Mike shared that he has developed an intuitive protocol for dealing with such cases. The most important thing is to keep or make people talk. He says:

- In everything that Chief Mike does for his community there is a feeling of belonging to the community. He does not see himself as a first-line bureaucrat but as an critical element of the community. His alegiance is much more to the community than to the administrative, security and justice systems.

- It is very important to know the people and have their trust. Chief Mike never orders parties to come to hearings, provide evidence or comply with decisions. He invites, listens, jokes, discusses solutions.

- Respect is related to trust. Chief Mike aims to respect everyone equally and believes that his neutrality, wisdom and energy earns him respect from the community. This helps him to intervene in disputes and resolve them effectively.

- As a community justice provider Chief Mike works 24/7. People come sometimes at night or during weekends to his office but also to his family house. Physical and social proximity is key for helping people to resolve problems.

- Chief Mike does not see problems as legal, economic or cultural. “Our office cut across all the ministries in Kenya, education, agriculture.” His works to solve people’s problems regardless of their label.

- Knowing the formal and informal justice infrastructure is critical. Chief Mike works upwards and downwards with various state and communal institutons. He does not expect his people to know the pathways; it is important that he knows them.

- When people keep talking, they will find a way. The role of the neutral is to make them feel safe, welcome and to dismantle the many barriers that might stop people from talking.

- Recognising emotions is key for resolving disputes. Emotions might be interpersonal but might span over families, clans or tribes.

- Knowing the root causes of the problems is very important for de-escalating and for achieving sustainable solutions.

- Next, Chief Mike stresses the importance of giving all parties a voice. People need to feel listened to in such situations.

- The neutral third party should refrain from instructing the parties from a power position. Mike says that he avoids directing and refers to soft power.

- He considers remaining neutral as very crucial.

- Chief Mike relentlesly seeks resolutions by agreement. “So it seems to me your main goal is not to find, let’s say, legal truth or to come to the rule, what the rule says, but to achieve an agreement between people.”

- In the last 5 years, Chief Mike has accumulated dispute resolution skills and approaches that help him. He wishes he knew about these tools before and recognises that some of the skills are experiential – you have to go through certain number of dispute resolution sessions to gain insights.

- Getting involved in resolving disputes is stressful. Chief Mike stresses the importance of self-care. “So I pile people’s mistakes. So there is at that time that I’m going to bust. “

- Lastly, Chief Mike stressed the importance of solving not only the dispute but also restoring the relationship between the affected individuals.

Key learnings

- We saw the context and dynamics of one of the most prevalent legal problems – disputes over the boundaries of land plots.

- Seemingly small border inconsistencies cause significant grievances and sometimes escalate out of hand.

- In people’s perspective land has not only economic value; it has considerable emotional and relational value.

- Procedural justice is key. People directly or indirectly involved in the problem want to have a voice and to be treated with dignity and respect, and the third party is neutral and objective.

- Formal and informal systems and approaches can re-enforce themselves. The dispute resolution experience of Mike benefits from the fact that the land is measured and recorded in the cadastre. The formal system benefits from the mediation and facilitation through which the informal justice practitioner applies the objective criteria of the legal rules.

- The major outcome of a land problem is not the proper demarcation of the borders. The most desired result is the restoration of the parties’ relationships.