User-friendly Contracts Policy Brief

Contracts are essential tools for enabling cooperation between people. Although legal professionals are comfortable with such documents, most people find contracts difficult to understand. A growing group of scholars and innovators is trying to make contracting a more positive experience.

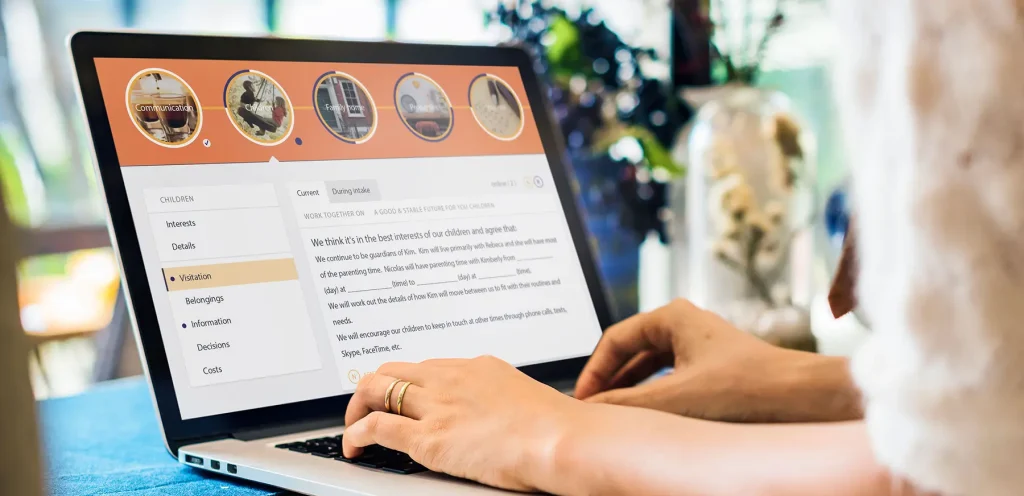

Case: Avodocs

CASE Avodocs Download Photo by Avodocs User-Friendly Contracts – Policy Brief / Case: Avodocs Key fact and figures Year of establishment 2019 Type of justice problems addressed Business Geographical scope USA, Canada, South Africa, Ukraine, Netherlands, Germany, Luxembourg, United Kingdom, Estonia, and Lithuania Legal entity Private company Regulatory embeddedness Independent of the government, no working […]

Case: World Commerce and Contracting

CASE World Commerce and Contracting Download Photo by World Commerce and Contracting User-Friendly Contracts – Policy Brief / Case: World Commerce and Contracting Key fact and figures Year of establishment 1999 Scope of service Professional Membership Association, Research Body, Education, Events, Advocacy Geographical scope Global Legal entity Not for profit organisation Type of justice problems […]

Case: DIYlaw

CASE DIYLaw Download Photo by DIYLaw User-Friendly Contracts – Policy Brief / Case: DIYLaw Key fact and figures Year of establishment 2015 Scope of service Privacy Policy, Non-Disclosure Agreements, Employment Contracts, Tenancy Agreement, Board resolutions Type of justice problems addressed Employment and business Geographical scope West Africa, Canada, USA, UK Legal entity Private company Relationship […]

Case: Comic Contracts

CASE Comic Contracts South Africa Download Photo by Creative ContractsUser-Friendly Contracts – Policy Brief / Case: Comic Contracts Key fact and figures Year of establishment 2017 Scope of service Topics on which contracts are offered: Employment Contracts Outgrower Agreements Photographic Consents Medical Research Consents Financial Services Provider Agreement Funeral Insurance Renters Insurance General Insurance Grant […]