Justice Needs and Satisfaction in Nigeria 2024

An update on the justice gap and a deeper understanding of the evolution of legal problems

August, 2024

Explore Data of Countries

Find out how people in different countries around the world experience justice. What are the most serious problems people face? How are problems being resolved? Find out the answers to these and more.

*GP – general population; *HCs – host communities; IDPs* – internally displaced persons

Explore guidelines for solving and preventing justice problems. They recommend interventions, which can support lawyers, paralegals and other practitioners in their work.

Justice Services

Innovation is needed in the justice sector. What services are solving justice problems of people? Find out more about data on justice innovations.

The Gamechangers

The 7 most promising categories of justice innovations, that have the potential to increase access to justice for millions of people around the world.

Justice Innovation Labs

Explore solutions developed using design thinking methods for the justice needs of people in the Netherlands, Nigeria, Uganda and more.

Creating an enabling regulatory and financial framework where innovations and new justice services develop

Rules of procedure, public-private partnerships, creative sourcing of justice services, and new sources of revenue and investments can help in creating an enabling regulatory and financial framework.

Forming a committed coalition of leaders

A committed group of leaders can drive change and innovation in justice systems and support the creation of an enabling environment.

Problems

Find out how specific justice problems impact people, how their justice journeys look like, and more.

An update on the justice gap and a deeper understanding of the evolution of legal problems

August, 2024

Photo by: Tolu Owoeye, via Shutterstock

In April 2023, HiiL launched its Justice Needs and Satisfaction (JNS) Nigeria 2023. Based on survey interviews with 6,573 Nigerians from all over the country, the report provides a unique people-centred picture of the justice landscape in Nigeria. It shows that legal problems are a common experience for Nigerians and that the majority of these problems are dealt with outside the formal justice system. The report highlights the scale of the justice gap in Nigeria and is a call to action for the implementation of people-centred justice policies.

But what happened afterwards to the people we interviewed during that first wave of data collection? Did they manage to resolve the legal problems they were dealing with at the time? If so, were they able to move on with their lives after they managed to resolve their most serious problems? Or did they encounter new legal problems?

In order to find answers to these questions, in January 2024 a team of enumerators travelled all over Nigeria once more to talk to the same people we interviewed for the JNS Nigeria 2023. For this second wave of data collection, we managed to conduct interviews with 4,912 people, or around 75% of the initial sample. For a more detailed explanation of the methodology and the panel, click here.

The first round of interviews for the study (which informed the JNS Nigeria 2023 report, which provides a more detailed explanation of the full methodology and the original panel recruited for this study) were conducted in November and December 2023. At that time, enumerators from Communication & Marketing Research Group Limited (CMRG) interviewed 6,573 Nigerian adults from all six geopolitical zones.

After publication of the report, we organised a meeting with the reference group (consisting of justice experts and key stakeholders from various Nigerian organisations who have guided HiiL throughout this project) in October 2023 to discuss the second wave of the study. Based on their input and suggestions, we finalised the questionnaire used for the second round of panel interviews. After training the enumerators (many of whom were involved in the first wave of data collection), fieldwork took place in January 2024, just over a year after the first wave of data collection.

Using contact details collected during the first interviews, we were able to relocate 4,912 people from the original panel. This is around 75% of the original sample, which is just above the average retention rate for longitudinal studies. The majority of ‘lost’ respondents could simply not be found anymore; a very small minority did no longer want to participate in the study.

Importantly, there are no major significant differences between the people who were interviewed again and those who dropped out of the study. Older people, people with secondary education or higher, and people who reported one or more legal problems in wave one are slightly more likely to have been interviewed a second time, but the differences are rather small. This means the sample of the second wave of data collection remains representative of the entire Nigerian adult population.

The respondents who were not retained in the second wave of the study were replaced by new respondents with similar demographic characteristics, such as gender, age, and the location where they lived. These new respondents (n = 1,395) were used to ensure accuracy of the findings, but have not been included in the analysis of the current report.

In May 2024, HiiL presented the preliminary study findings to the reference group as part of a triangulation workshop. The reference group provided valuable feedback, interpretations, and explanations, greatly enhancing the final report. A third wave of data collection will take place in January 2025, concluding the current panel study project.

The experiences captured during the second wave of data collection provide new insights, but ultimately confirm what the original report already concluded: business as usual is not enough to close the justice gap in Nigeria. Instead, a transformation is needed that prioritises the Nigerian people through a people-centred approach to justice.

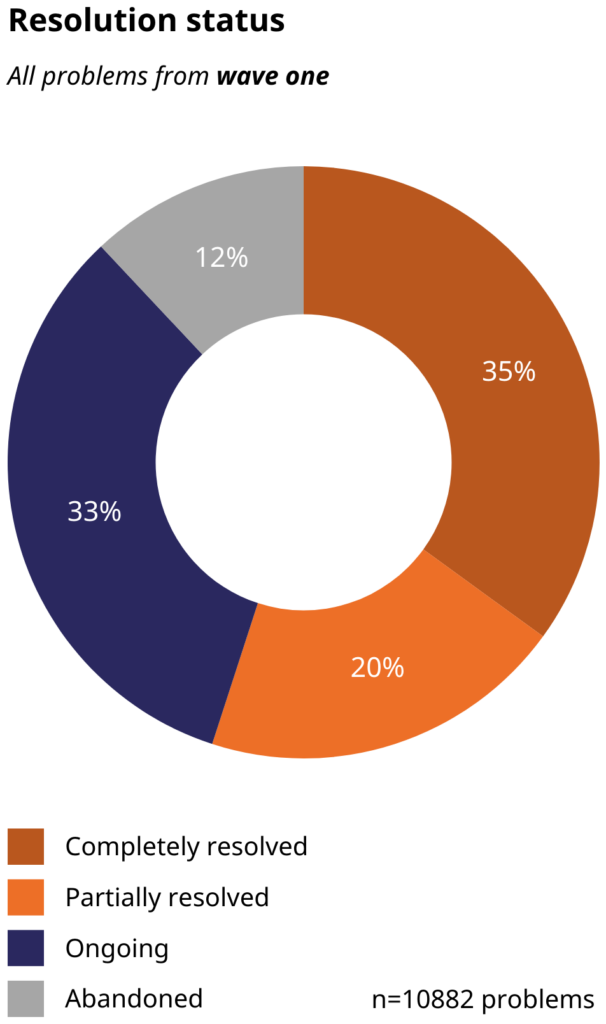

The JNS Nigeria 2023 showed that around 81% of Nigerians had experienced one or more legal problems in the past year, with many people facing multiple problems. Approximately 55% of these problems were either partially or completely resolved and about 82% of these solutions were deemed fair or very fair.

Around 33% of all legal problems were still in the process of being resolved, while 12% had been abandoned, meaning people either ceasing their efforts to find a resolution or never attempting to do so in the first place.

The number of unresolved and unfairly resolved problems together constitute the justice gap: The difference between the demand for justice and the actual justice people get. The number of ongoing problems could be seen as the current demand side of justice: These are the legal problems people for which people are still trying to find a fair resolution.

To understand the evolution of the justice gap and the demand for justice, the second wave of data collection looked at the following types of legal problems:

By measuring the current status of these three types of problems we can assess the justice landscape in Nigeria one year after publication of the JNS report and gain a deeper understanding of the nature and evolution of legal problems.

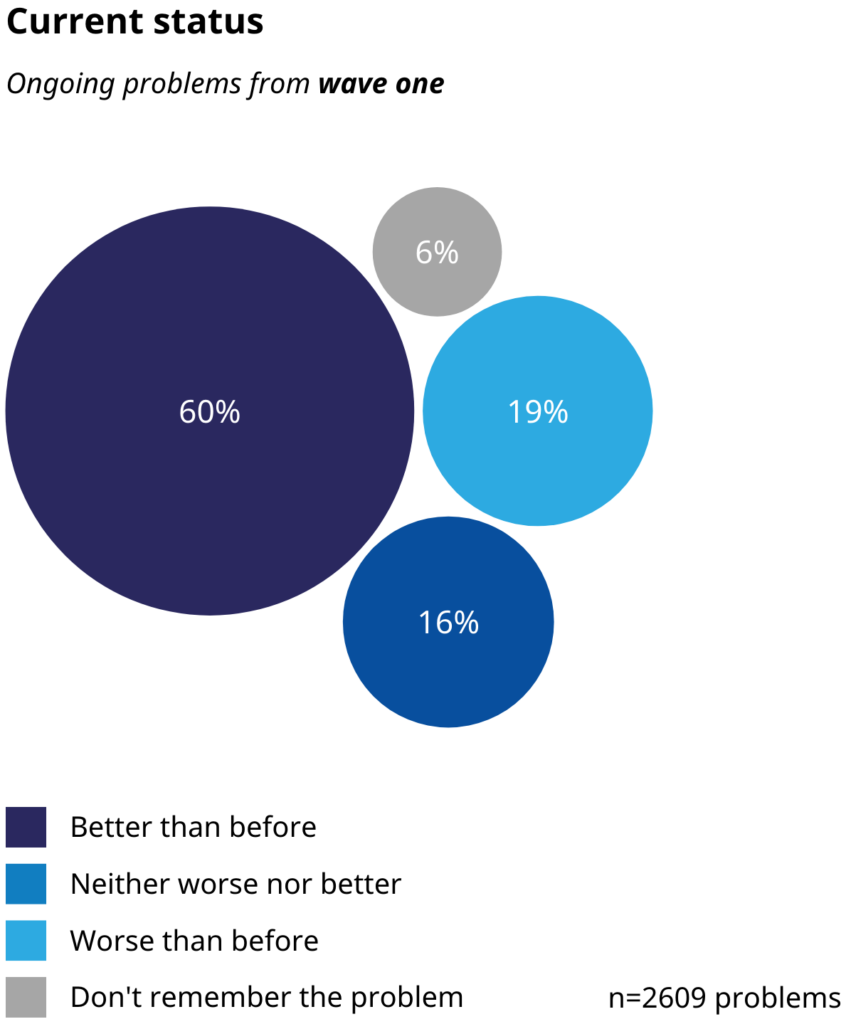

One in three problems reported during the first wave of data collection was still in the process of being resolved at the time of the interview. During the second interview, we therefore asked people how these problems had evolved since the first time we spoke.

The good news is that in 60% of the cases, people felt that the situation had improved. Around 16% of problems are neither worse nor better, while 19% have become worse. Only 6% of problems could not be remembered, mostly problems that were considered less serious at the first interview.

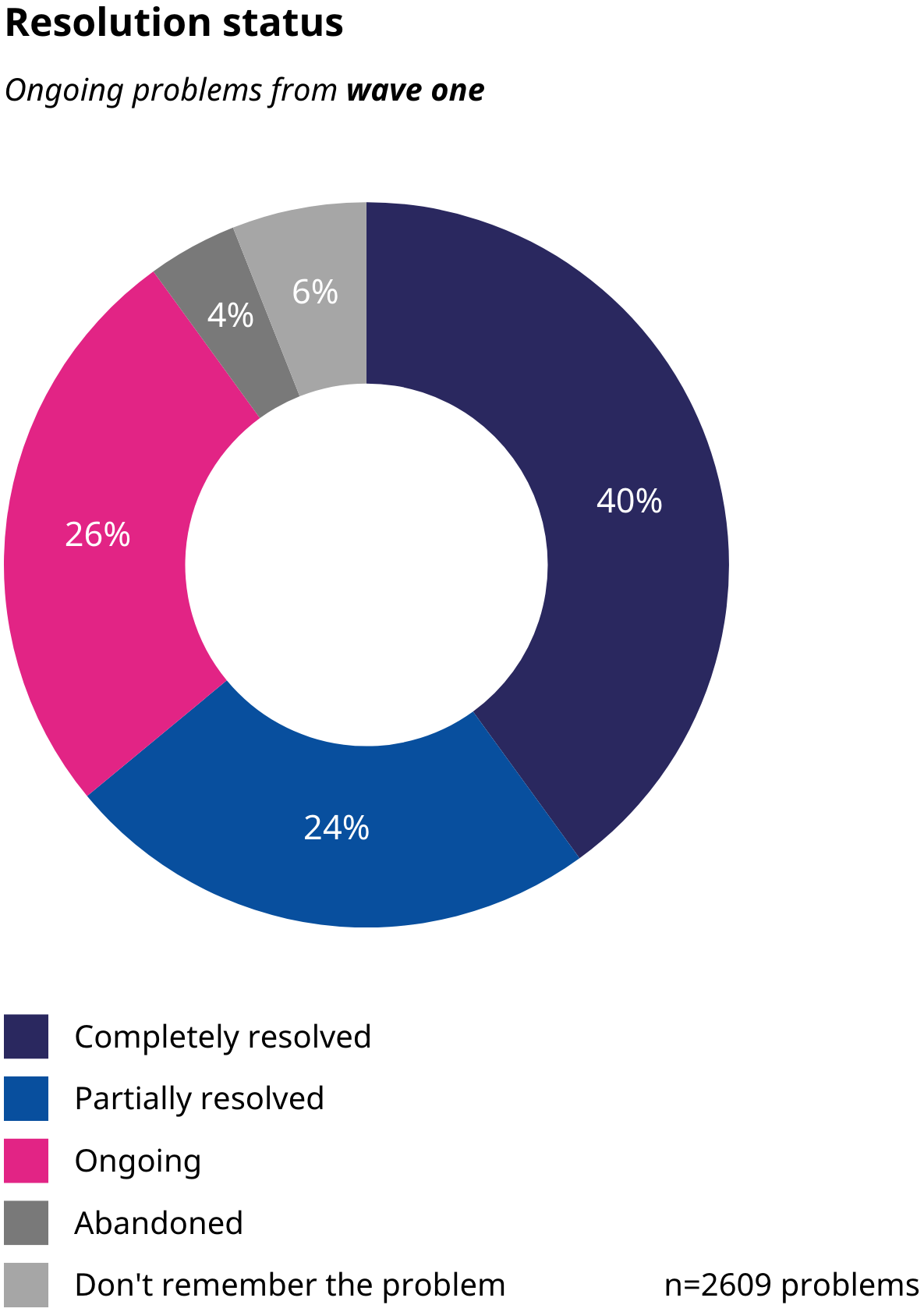

Not surprisingly, the majority of legal problems that are assessed as better than before, have been resolved in the meantime. More than a year after the first interview, around 40% of ongoing problems have been fully resolved and another 24% partially resolved. In other words, almost two out of three ongoing problems found a solution with time, narrowing the justice gap. It means around 77% of all legal problems from the first wave reached a solution within two years, a positive sign for the justice sector in Nigeria.

Around 26% of the ongoing problems from wave one were still in the process of being resolved at the time of the second interview. Even after more than one to two years, these people still are trying to find justice in order to be able to move on with their lives. These are some of the most serious problems people are dealing with, having long lasting negative effects on various aspects of their lives.

Finally, only 4% of ongoing problems from wave one have been abandoned, illustrating once more that Nigerians do not easily give up on finding solutions for their legal problems.

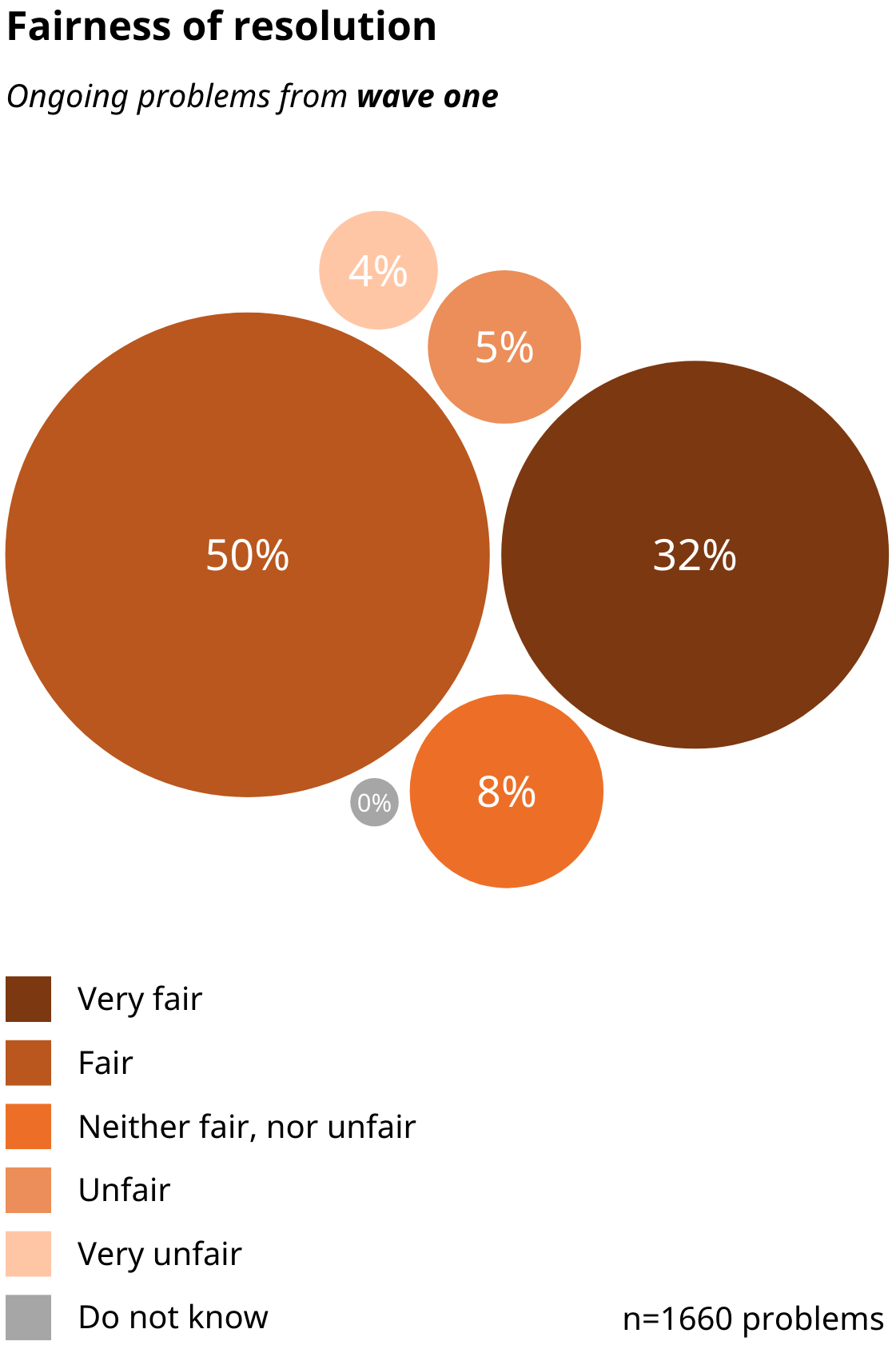

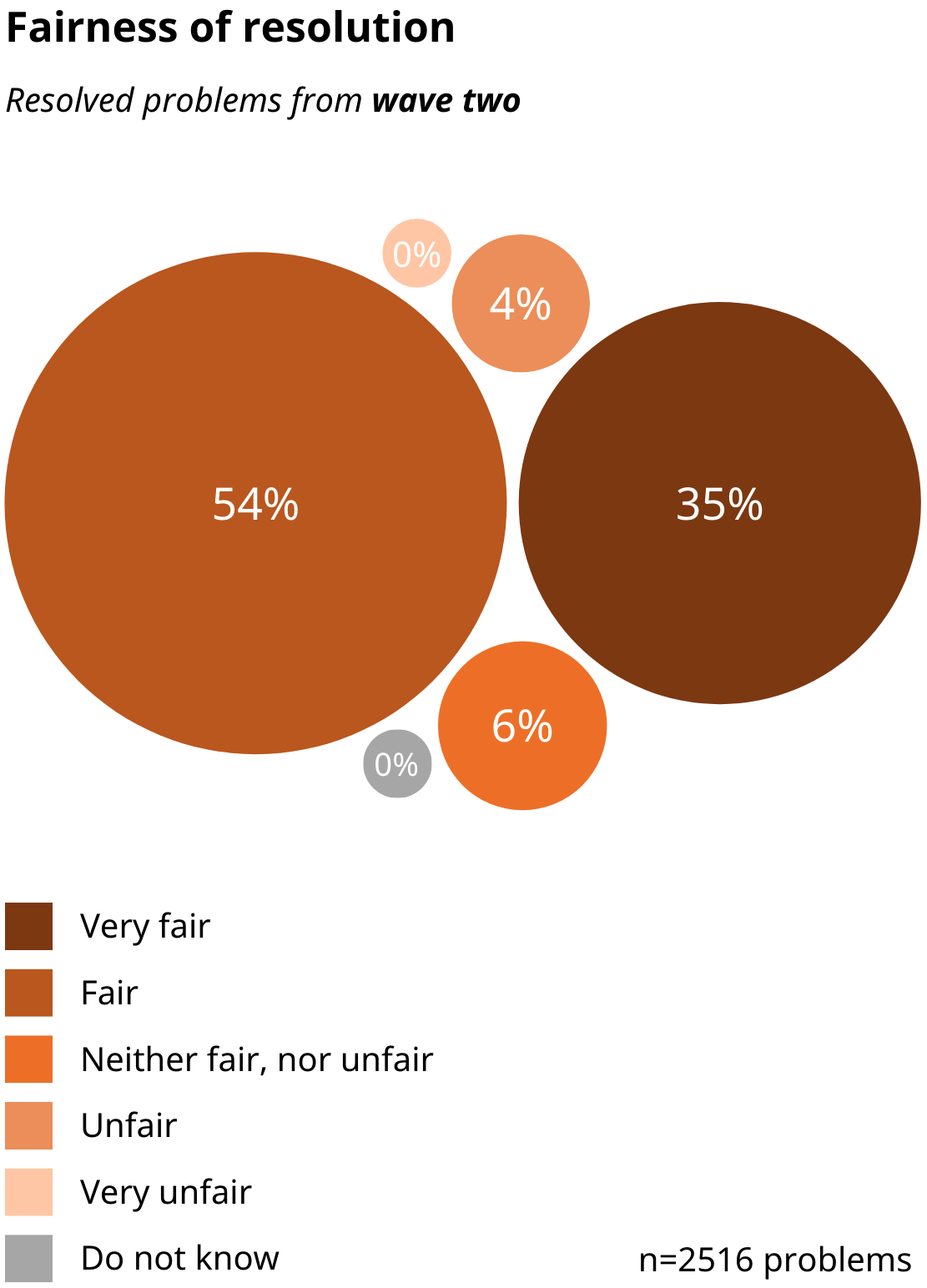

As we already found in the JNS Nigeria 2023, the majority of resolutions are considered fair or even very fair. Around 82% of resolutions are seen as (very) fair, thus highlighting that people who manage to find the justice they are seeking are generally satisfied with the outcomes they get.

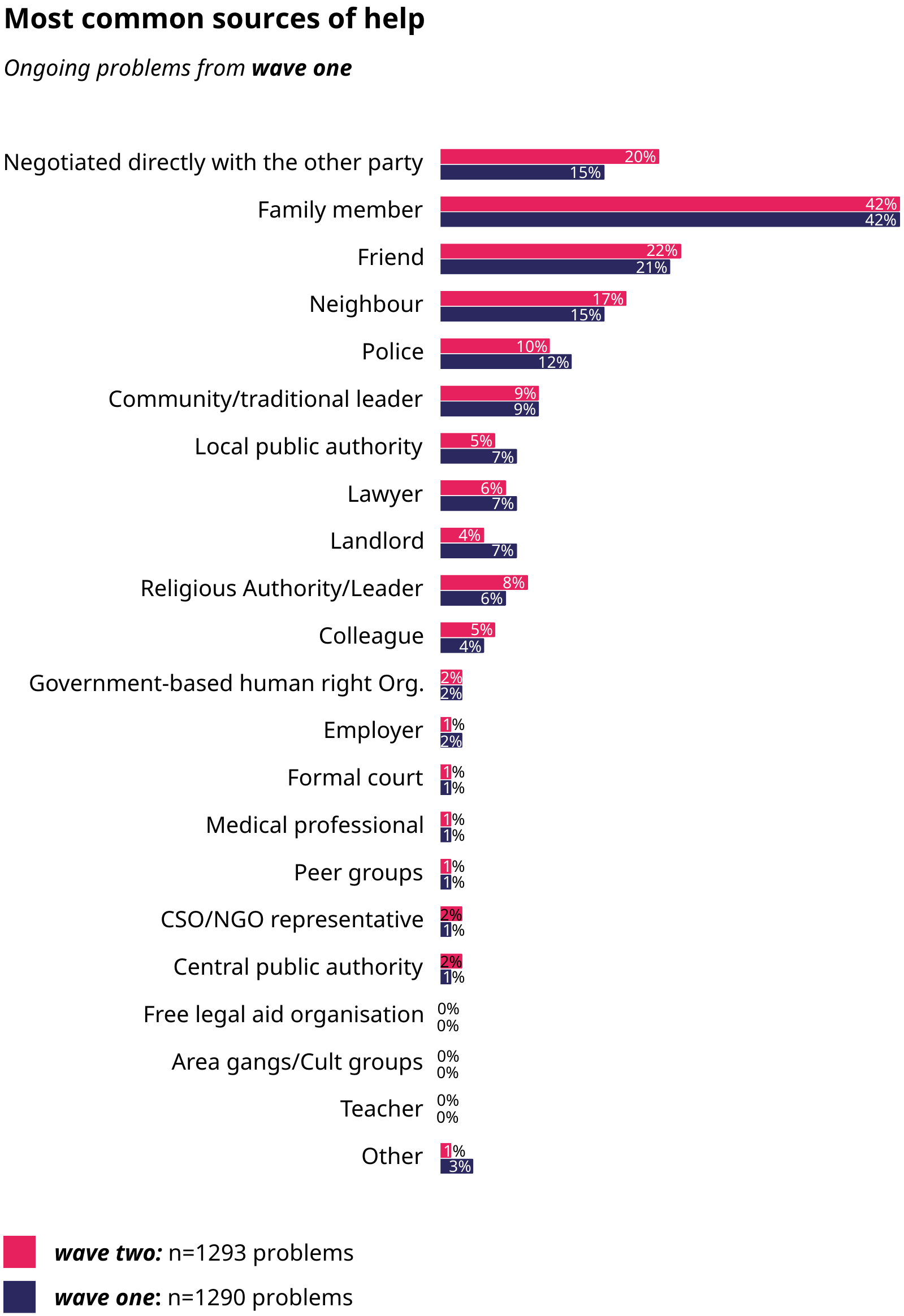

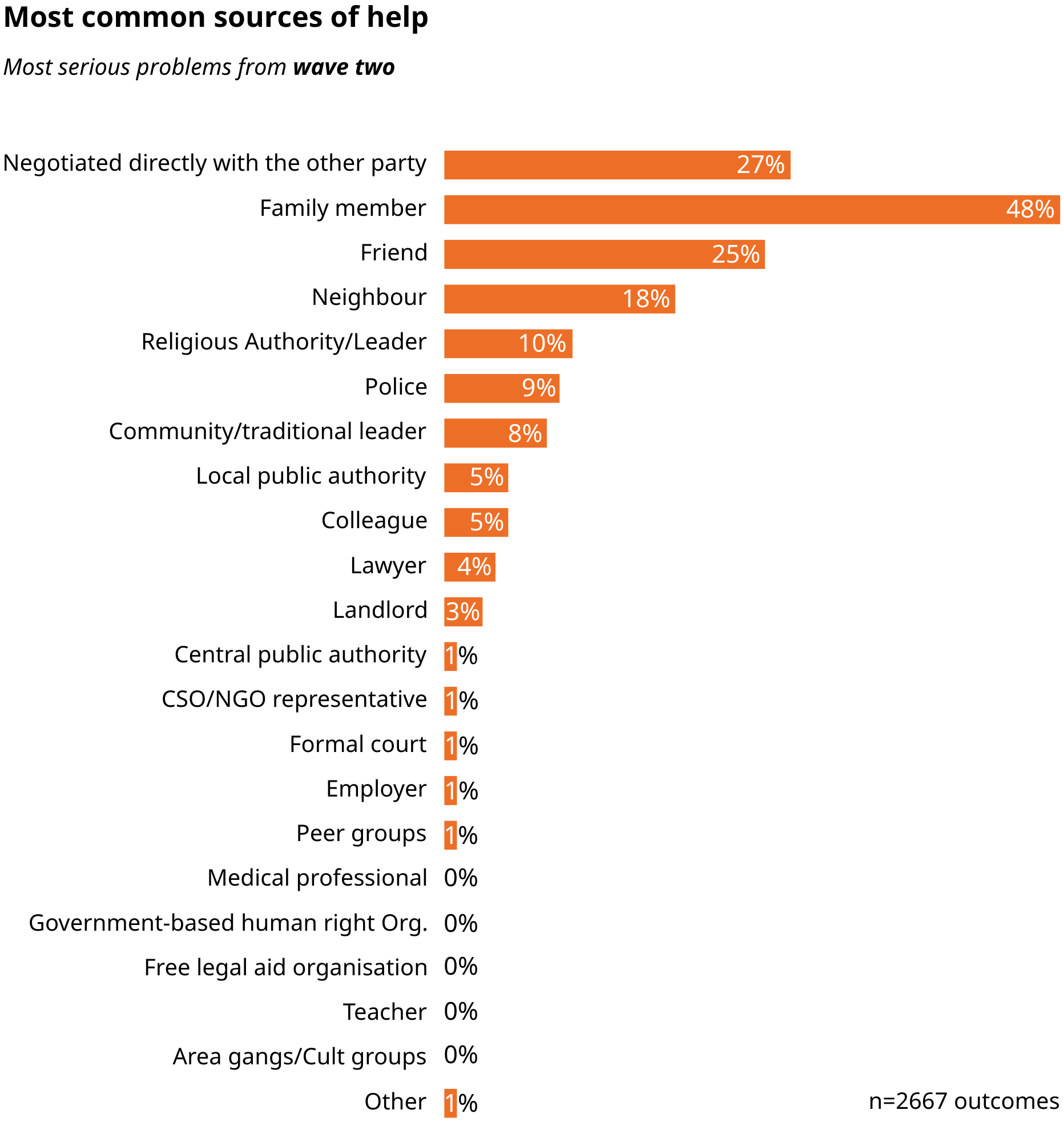

Just like in the first interview, in the second interview we asked people what steps they took to try to resolve their most serious problem. For the most serious ongoing problems from wave one, almost everyone had taken some sort of (additional) action since the first interview. Only 13% of people did not take any action. The other 87% obtained help from a wide variety of sources.

The most common sources of help are nearly identical to what we found in the JNS Nigeria 2023. Social networks (family members, friends, neighbours) play a key role in helping people to resolve their most serious problems. After that, and much less common overall, the most common sources of help are the police and community and religious leaders.

Despite the fact that these are legal problems that have been ongoing for a long period of time and were considered the most serious problem during the first interview, still only 6% of people turned to a lawyer and only 1% went to a formal court. The idea that people first try to solve problems themselves or with help of their personal network and, if that does not work, might opt to engage the formal justice system, is not supported by the data. Instead, these results further confirm that the majority of legal problems in Nigeria, including the most serious ones that are dragging on over longer periods of time, are dealt with outside the formal justice system.

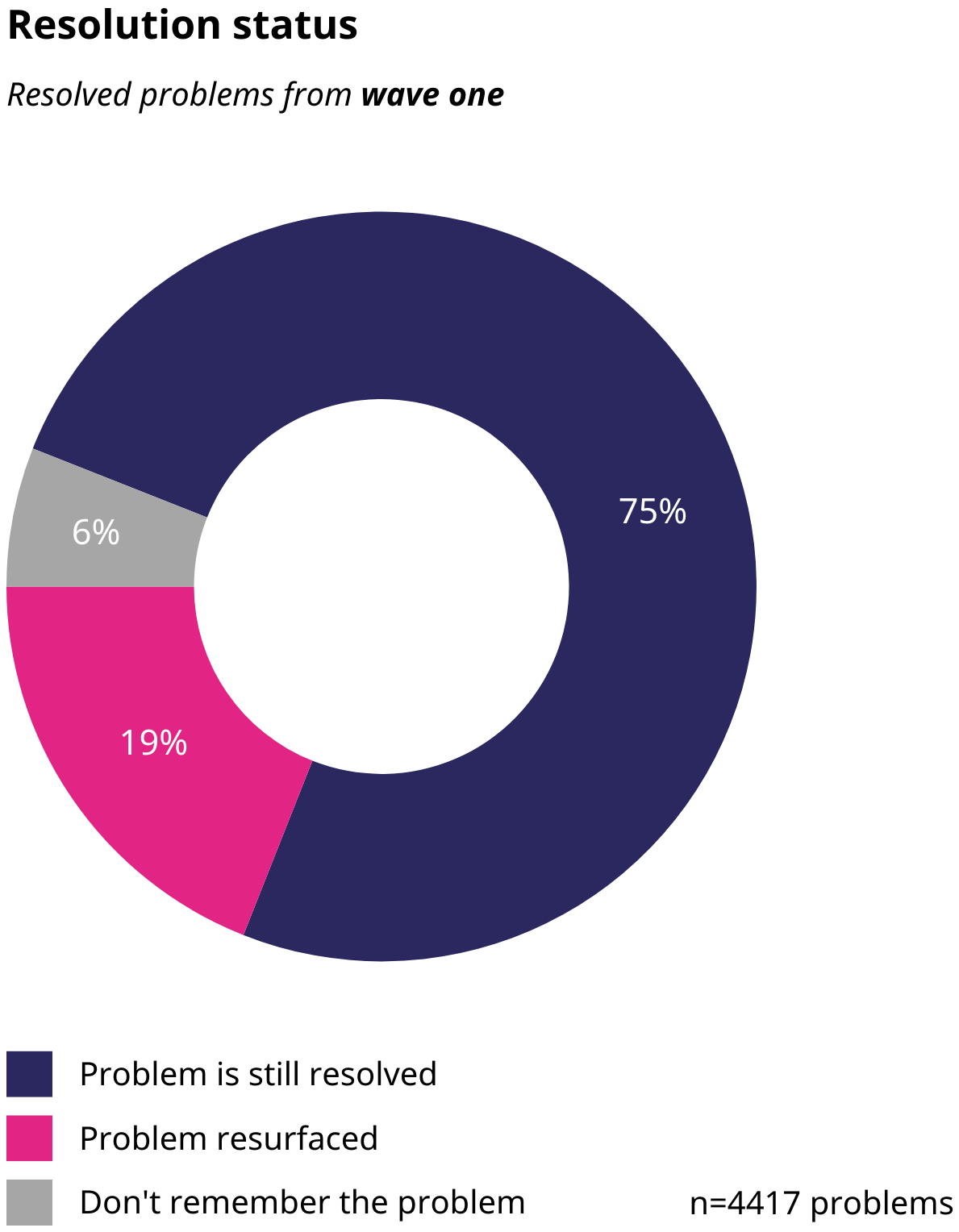

Around 55% of all problems reported in wave one were partially or completely resolved at that time. However, not all resolutions are created equal. Over a year later, three out of four problems are still considered resolved. At the same time, 19% of problems that were initially resolved resurfaced again in the following year, thus widening the justice gap. This constitutes around 11% of all legal problems reported in wave one.

This shows that legal problems are not static and resolutions can be temporary. While the justice gap is dynamic, the overall demand for justice remains relatively stable. The resolution of ongoing legal problems helps to narrow the justice gap with 22%, but resurfacing problems that were considered resolved in turn widen the justice gap with 11%.

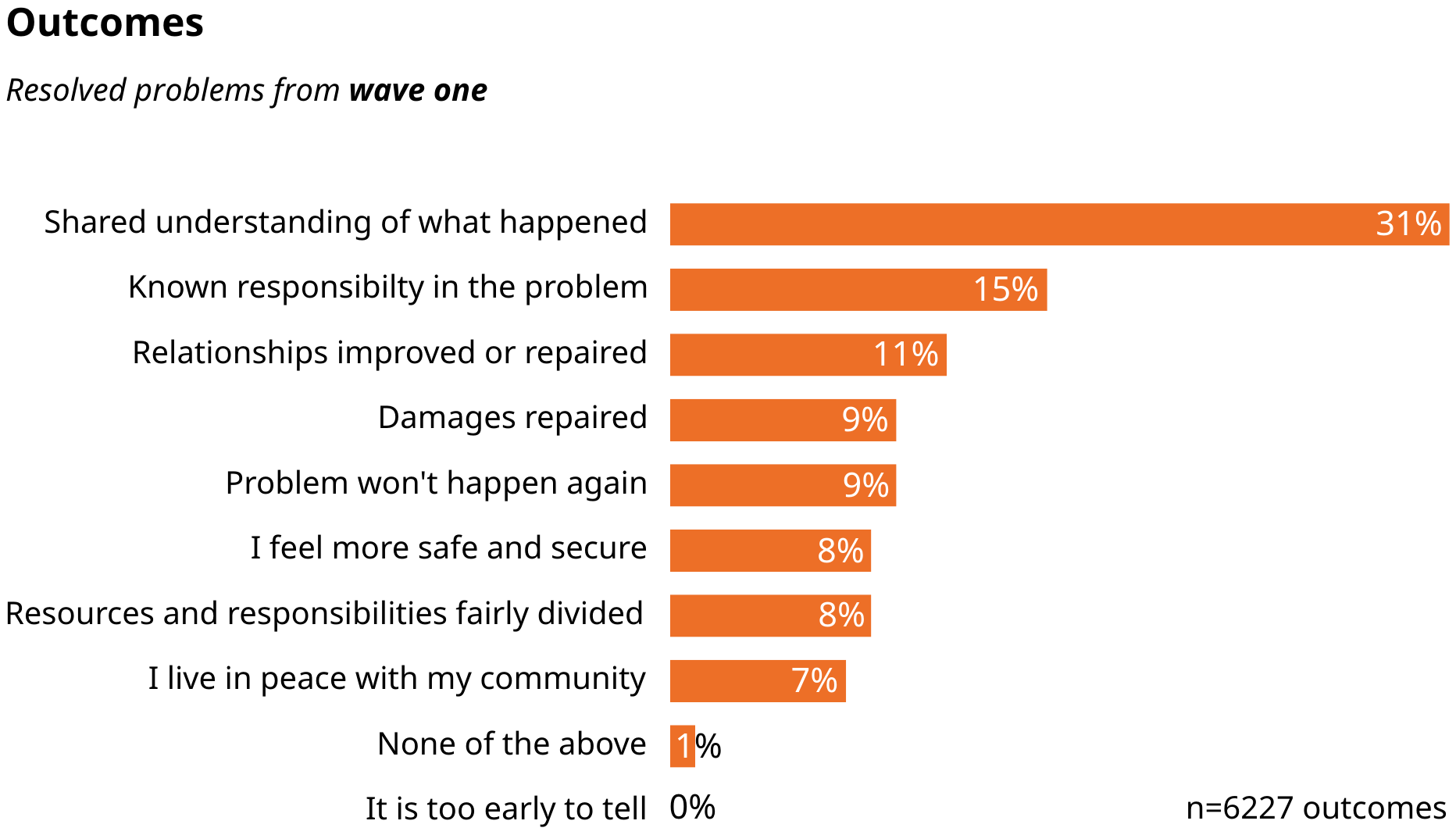

Resolution of legal problems is only one part of justice. Such resolutions ideally lead to positive outcomes in people’s lives. For every resolved problem from wave one that was still resolved during the second interview, we asked people about the outcomes beyond the resolution.

Almost everyone experiences one or more positive outcomes following the resolution of a legal problem. The most common outcome is having a shared understanding of what happened. Almost one in three of the outcomes collected related to this. Next, another knowledge-related outcome appears, related to knowing the responsibilities of the problem. After that, the third most common outcome is improvement or repair of relationships. Less common outcomes are about preventing the problem from happening again and feeling more safe and secure.

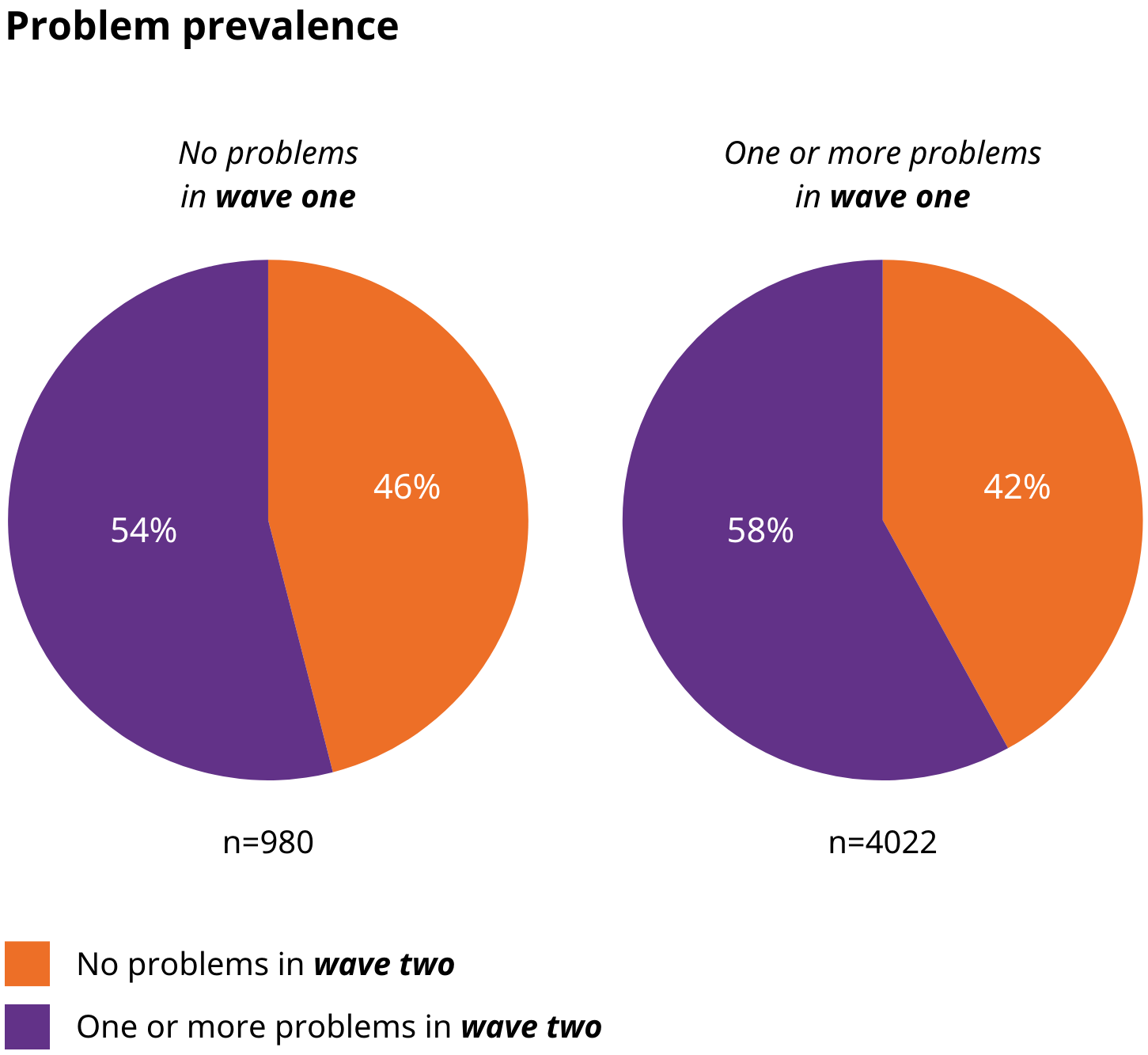

With ongoing problems getting resolved and resolved problems resurfacing, the justice gap in Nigeria is in constant flux. Another complication is the occurrence of new legal problems since wave one of the study. Around 58% of people experienced one or more new legal problems between the first and the second interview. On average they reported 1.44 problems per person.

Both these numbers are lower than those reported during wave one, when 81% of Nigerians reported on average two problems per person. Despite the survey asking about problems that first appeared in the previous twelve months, it is likely that during the first interview more problems were reported that had started more than a year ago and still continued at the time of the interview.

People who reported one or more legal problems during wave one are slightly more likely to report one or more new legal problems in wave two (58% versus 54%). In other words, it seems that experiencing legal problems increases the risk of subsequently experiencing more legal problems. Another explanation could be that certain people are more prone to experience legal problems than others.

More than half of the people who did not report a legal problem during wave one did experience a legal problem in the subsequent year. This means that over a longer period of time even more people encounter legal problems than the 81% reported in the JNS Nigeria 2023. Only 9% of people reported no legal problems during both interviews.

There are large differences between different problem categories. Indeed, most problem categories have no statistically significant effect on the likelihood of experiencing a new legal problem in the year after. Only two problem categories significantly increase the likelihood of experiencing a new legal problem in the following year: land problems and domestic violence. These are among the most serious problem categories in the JNS Nigeria 2023 report. Around 65% of people experiencing a land problem experience another legal problem in the following year; for victims of domestic violence this is 64%. In both cases, this is significantly higher than the average of 58%.

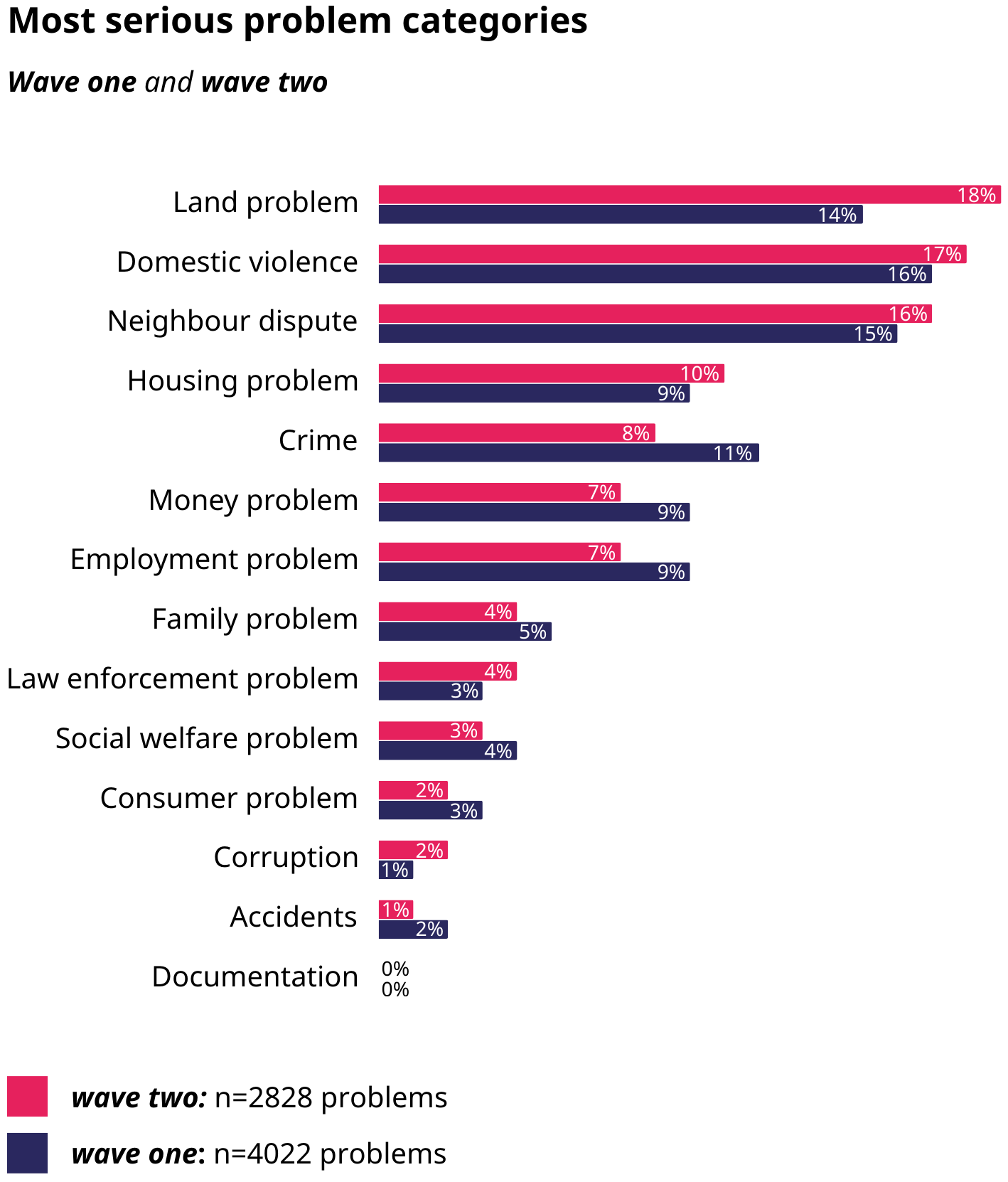

When looking at the most serious problem categories, it is remarkable how similar the new problems are to those in the JNS Nigeria 2023. Although there are some small changes (most notably a decrease in people reporting crimes, money problems, and employment problems and an increase in people reporting land problems), the three most serious problem categories in both interview rounds are exactly the same: domestic violence, land problems, and neighbour disputes.

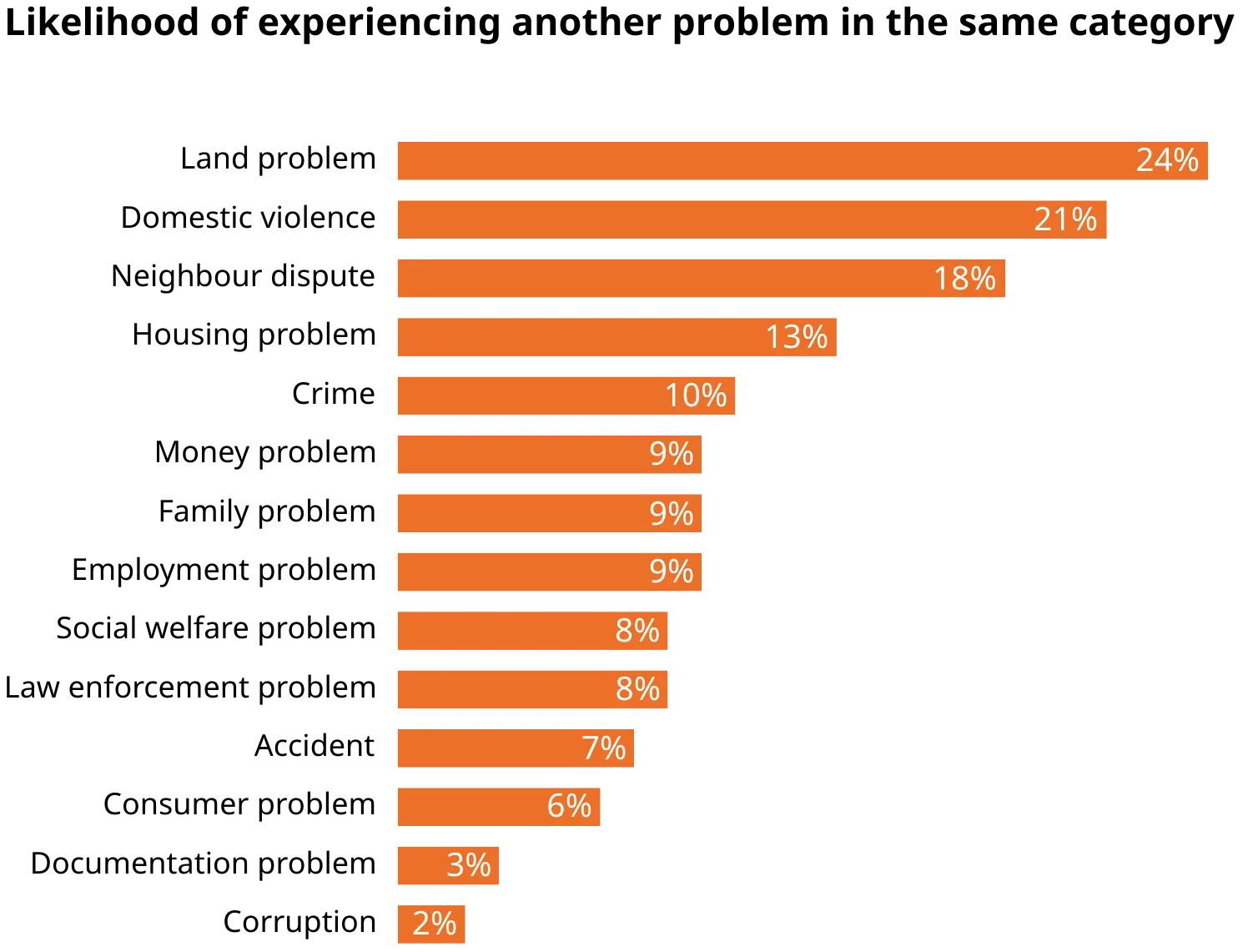

We also looked at how likely it is that people experienced similar legal problems as their most serious problem of the first interview. In other words, how likely is it that people experience land problems or neighbour disputes several times in a row? The data shows that people experiencing a problem in one of the three most serious problem categories are also most likely to experience a new problem in the same category.

Around 24% of people experiencing a land problem end up experiencing another land problem within a year. For victims of domestic violence this is 21%. Besides land problems and domestic violence, neighbour disputes also have a high likelihood of leading to additional neighbour disputes. To what extent these are entirely new problems or a resurfacing of old problems is often hard to distinguish, but it is clear that these problem categories have a high level of ‘stickiness’. This further emphasises the importance of finding durable solutions for these problem categories.

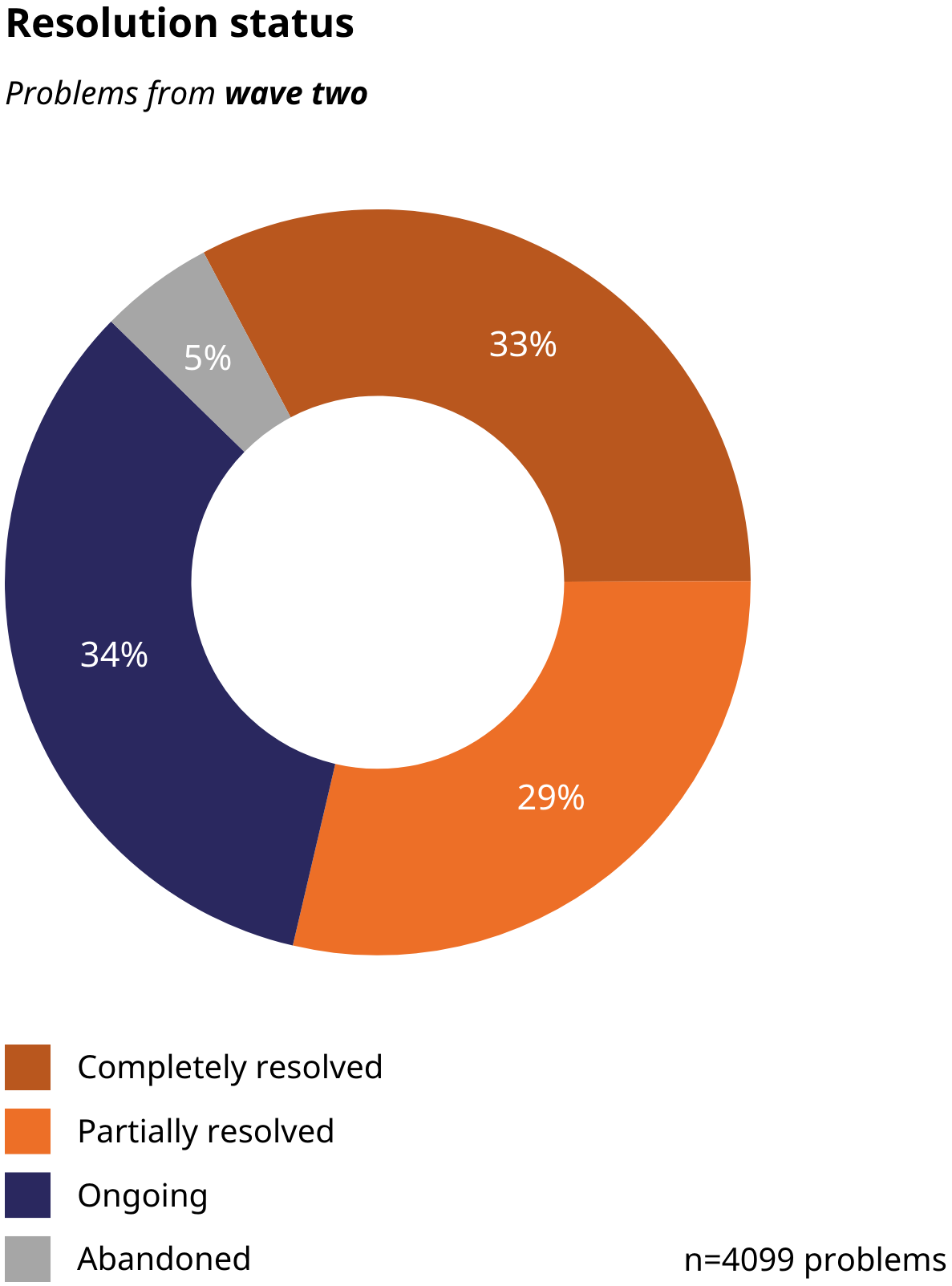

Many of these new problems were quickly resolved: around 62% was already partially or completely resolved at the time of the interview, while 34% of problems are ongoing and 5% have been abandoned. This resolution rate is slightly higher than in the JNS Nigeria 2023, supporting the idea that the first study included more longer-running legal problems.

Once again, the vast majority of these resolutions are assessed as fair or even very fair. It shows that people are generally satisfied with the resolutions they get, even though the majority of these are achieved outside the formal justice system.

As usual, we asked people what they did to try to resolve the most serious problems they reported in wave two. In light of the actions taken to resolve the problems reported in wave one, the results are not surprising. Around 94% took one or more actions and the sources of help they engaged are very familiar.

Social networks play a key role, especially family members. Outside the personal network, the most important actors are different religious and community authorities as well as the police. Lawyers and formal courts only play a marginal role in the provision of justice to ordinary Nigerians.

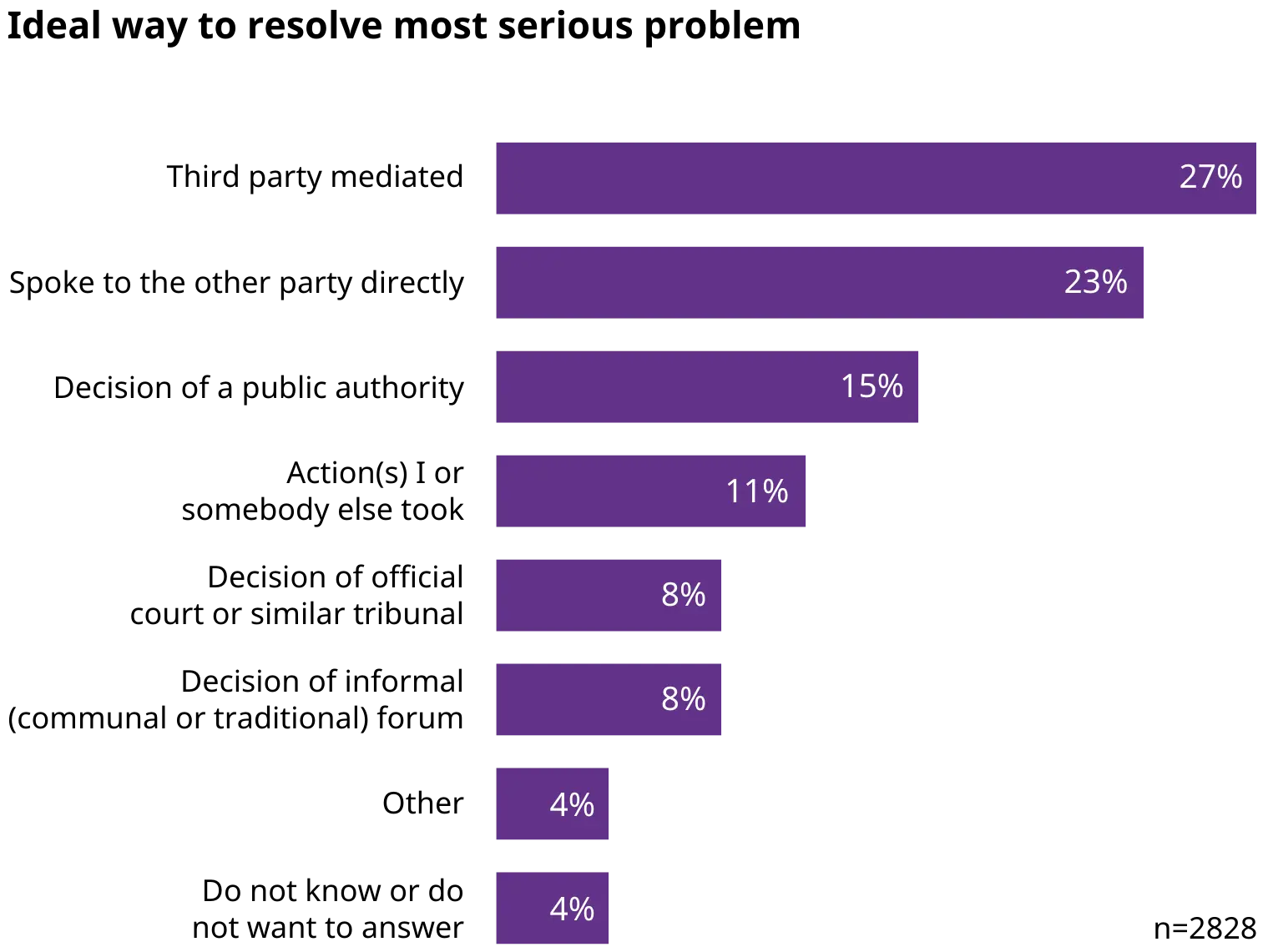

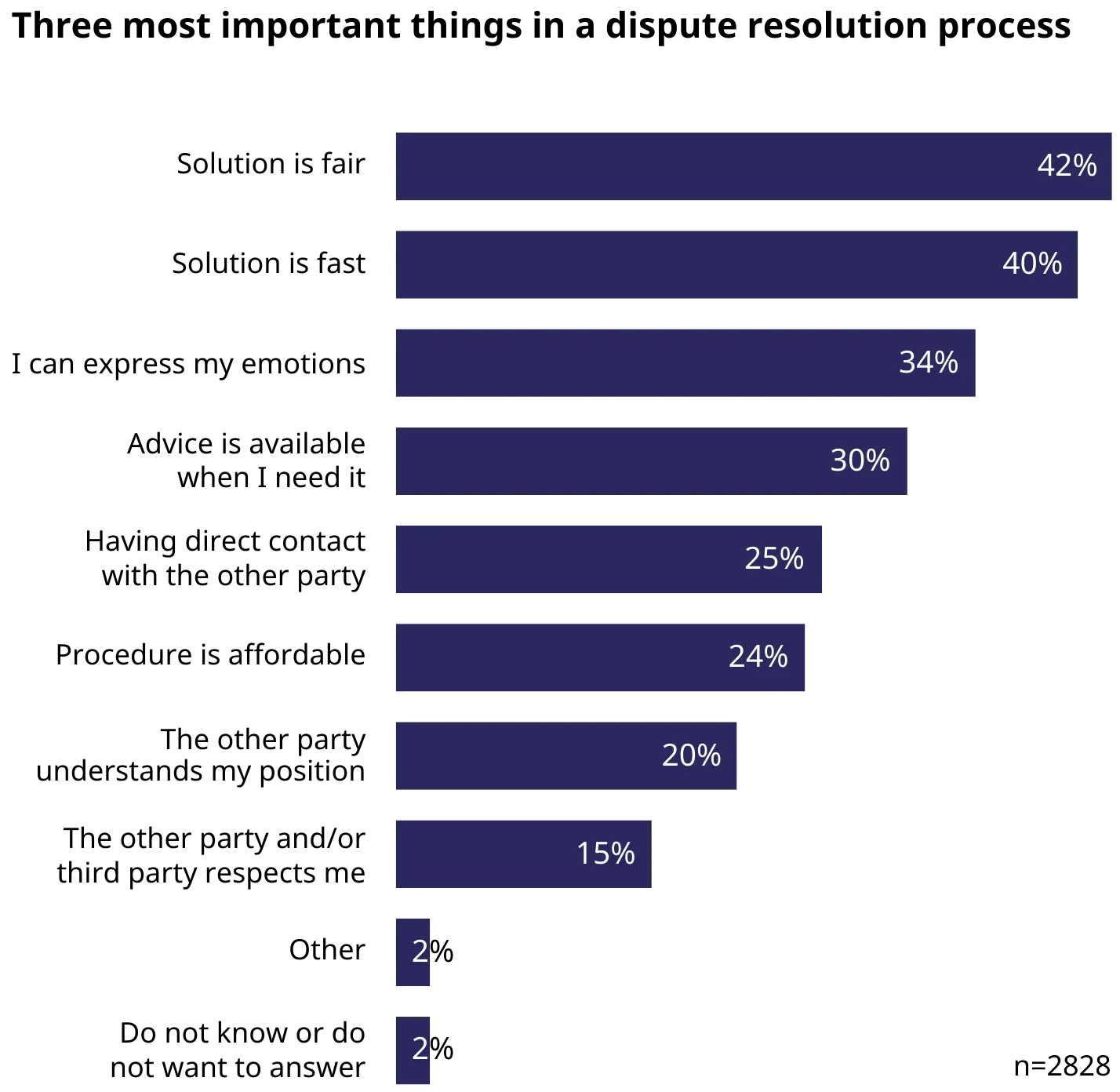

Nigerians experiencing legal problems have a strong desire to resolve these in order to be able to move on with their lives. This is clear from the overwhelming majority of people who take one or more actions to resolve their most serious legal problems and the low percentage of problems that get abandoned. In order to better understand what people seek when trying to resolve their legal problems, we asked people how they ideally would have gone about resolving their most serious problem.

The responses illustrate the wish of people to find amicable solutions without having to go to a formal court. Of course this depends on the nature of the legal problem, but half of the people expressed a preference for either solving the dispute directly with the other party or through mediation from a third party. Decisions of a court or a more informal mechanism are considerably less popular.

Besides their preferred resolution path, we also asked people about the most important elements of a dispute resolution process. The answers to this question reveal that the most important thing for people is a fast and fair solution. After that, the most common answers are the ability to express one’s emotions and the availability for advice when needed. It is interesting that affordability of the process is less of a priority for the majority of people, despite many people struggling to make ends meet. There is no significant difference in this preference between people with less or more financial means.

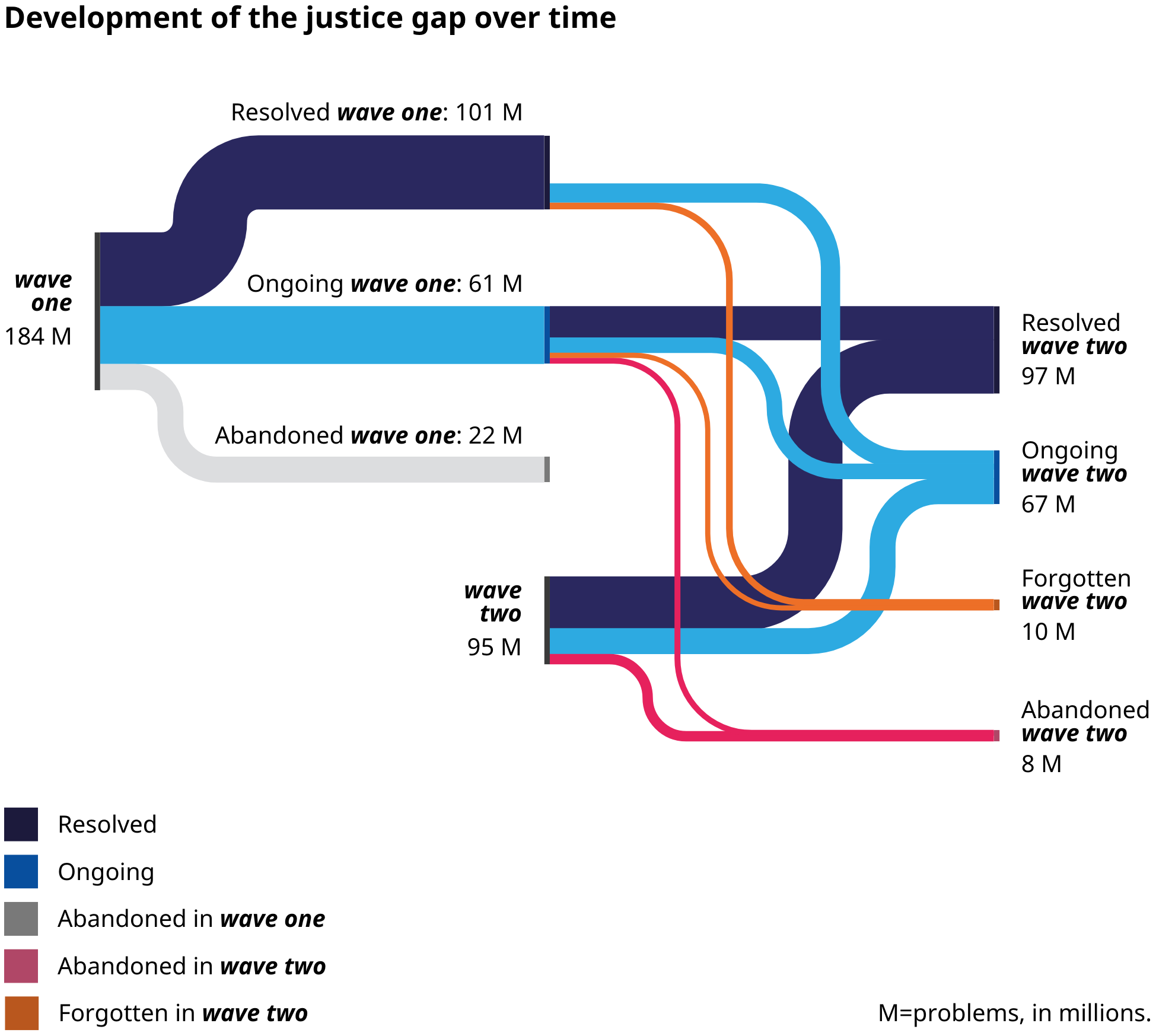

The justice gap in Nigeria is large and dynamic. Many problems get resolved, although this sometimes takes a long time. But these solutions are not always permanent, as legal problems resurface again or people experience similar problems after a while. In the end, as legal problems keep accumulating, the demand for justice in Nigeria is relatively constant and remains high.

In the JNS Nigeria 2023 we estimated that around 61 million legal problems were ongoing, with people still trying to find solutions. One year later, around 26% of these problems remain ongoing. This means around 16 million legal problems from wave one are still in need of a solution.

Besides these ongoing problems from wave one, around 19% of the 101 million legal problems that were considered resolved (or roughly 19 million legal problems) resurfaced again. Combining these two categories suggests around 35 million legal problems from wave one are still (or again) in need of a resolution one year later.

In the second wave of data collection, around 58% of people experienced on average 1.44 new legal problems. This means an estimated 95 million new problems happened in the last year. Although many of these were quickly resolved, around 34% remained ongoing at the time of the interview. This means 32 million new legal problems from wave two are still in the process of being resolved.

Combining the ongoing problems from wave one and wave two results in an estimated 68 million legal problems that are in need of a solution. In other words, the demand for justice in Nigeria is relatively stable over time, remaining consistently very high.

The graph below visualises the development of the justice gap over time. As older problems remain ongoing or resurface again, new legal problems also emerge in the meantime. Despite the high resolution rates, the result is an accumulation of ongoing legal problems and a consistently high demand for justice.

The JNS Nigeria 2023 highlighted land problems, domestic violence, and neighbour disputes as the most serious problem categories. The second wave of data collection confirms these problem categories as the most serious ones. People experiencing problems within these categories are more likely to experience similar problems further down the line, illustrating the importance of finding durable solutions for them.

What should such solutions look like? What Nigerians are saying to policy makers and justice practitioners is that they want fair and fast solutions through a process in which they are able to express their emotions. They also prefer to resolve disputes through direct negotiation or mediation rather than lengthy and complicated legal proceedings in a formal court. In order to close the justice gap and help people move on with their lives, innovative approaches outside the formal justice system are therefore crucial.

Some promising developments are already happening in Nigeria when it comes to people-centred justice programming, but more needs to be done. A national people-centred justice strategy would be a crucial step to make a firm commitment to closing the justice gap.

Table of Contents