Justice Needs and Satisfaction in Tunisia 2024

An update on the justice gap and a deeper understanding of the evolution of legal problems

November, 2024

Explore Data of Countries

Find out how people in different countries around the world experience justice. What are the most serious problems people face? How are problems being resolved? Find out the answers to these and more.

*GP – general population; *HCs – host communities; IDPs* – internally displaced persons

Explore guidelines for solving and preventing justice problems. They recommend interventions, which can support lawyers, paralegals and other practitioners in their work.

Justice Services

Innovation is needed in the justice sector. What services are solving justice problems of people? Find out more about data on justice innovations.

The Gamechangers

The 7 most promising categories of justice innovations, that have the potential to increase access to justice for millions of people around the world.

Justice Innovation Labs

Explore solutions developed using design thinking methods for the justice needs of people in the Netherlands, Nigeria, Uganda and more.

Creating an enabling regulatory and financial framework where innovations and new justice services develop

Rules of procedure, public-private partnerships, creative sourcing of justice services, and new sources of revenue and investments can help in creating an enabling regulatory and financial framework.

Forming a committed coalition of leaders

A committed group of leaders can drive change and innovation in justice systems and support the creation of an enabling environment.

Problems

Find out how specific justice problems impact people, how their justice journeys look like, and more.

An update on the justice gap and a deeper understanding of the evolution of legal problems

November, 2024

Photo by: Tolu Owoeye, via Shutterstock

In March 2023, HiiL launched its Justice Needs and Satisfaction (JNS) Tunisia 2023. Based on survey interviews with 5,008 Tunisians from all over the country, the report provides a unique people-centred picture of the justice landscape in Tunisia. It shows that nearly one in three Tunisian adults experience one or more legal problems every year and very few of these problems are resolved in a satisfactory manner. Only a small percentage of problems reach the formal justice system. The report highlights the scale of the justice gap in Tunisia and is a call to action for the implementation of people-centred justice policies.

But what happened afterwards to the people we interviewed during that first wave of data collection? Did they manage to resolve the legal problems they were dealing with at the time? If so, were they able to move on with their lives after they managed to resolve their most serious problems? Or did they encounter new legal problems?

In order to find answers to these questions, in January 2024 a team of enumerators called the same people we interviewed for the JNS Tunisia 2023. For this second wave of data collection, we managed to conduct interviews with 2,548 people, or around 65% of the people who shared their phone number during the first wave interview. For a more detailed explanation of the methodology and the panel, click here.

The first round of interviews for the study were conducted in October and November 2023. These interviews informed the JNS Tunisia 2023 report, which provides a more detailed explanation of the full methodology and the original panel recruited for this study. At that time, enumerators from One to One for Research and Polling interviewed 5,008 Tunisian adults from all 24 governorates of the country. Around 78% of them (3,906 people) agreed to share their contact details in order to be contacted for a follow-up interview one year later.

Just over one year later we contacted people by phone in order to hear from them how their legal problems had evolved and whether they encountered any new legal problems since the first interview. Out of 3,906 people who shared their contact details, we were able to contact 2,548 for the second interview (around 65%).

There are some small demographic differences between people who were interviewed again and those who dropped out of the study. In particular, men, people aged 25-64, and people who at least completed secondary education have a higher retention rate. On the other hand, there are no differences when it comes to rural and urban areas or people’s financial situation. Reinterviewed people are also slightly more likely to have reported one or more legal problems in the first interview, which is positive for our aim to track the development of legal problems over time. Overall we are confident the sample remains representative of the Tunisian adult population.

As the interviews for the second wave were conducted over the phone rather than in person, we had to adapt our methodology in certain areas. In particular, during the first interview we used a showcard listing over one hundred legal problems that people could use to identify whether they had experienced any of these in the year before. Obviously this approach was not an option for interviews conducted over the phone. Instead, we asked about broader problem categories and then tried to further specify which problem someone exactly experienced. It is possible this methodological choice might have had some effect on the findings of the second wave of the project.

In December 2024 we expect to conduct our third and final wave of interviews for the project.

The experiences captured during the second wave of data collection provide new insights, but ultimately confirm what the original report already concluded: business as usual is not enough to close the justice gap in Tunisia. Instead, a transformation is needed that prioritises the Tunisian people through a people-centred approach to justice.

The JNS Tunisia 2023 showed that around 31% of Tunisian adults experienced one or more legal problems in the past year, with many people facing multiple problems. Approximately 23% of these problems were either partially or completely resolved and about 48% of these solutions were deemed fair or very fair.

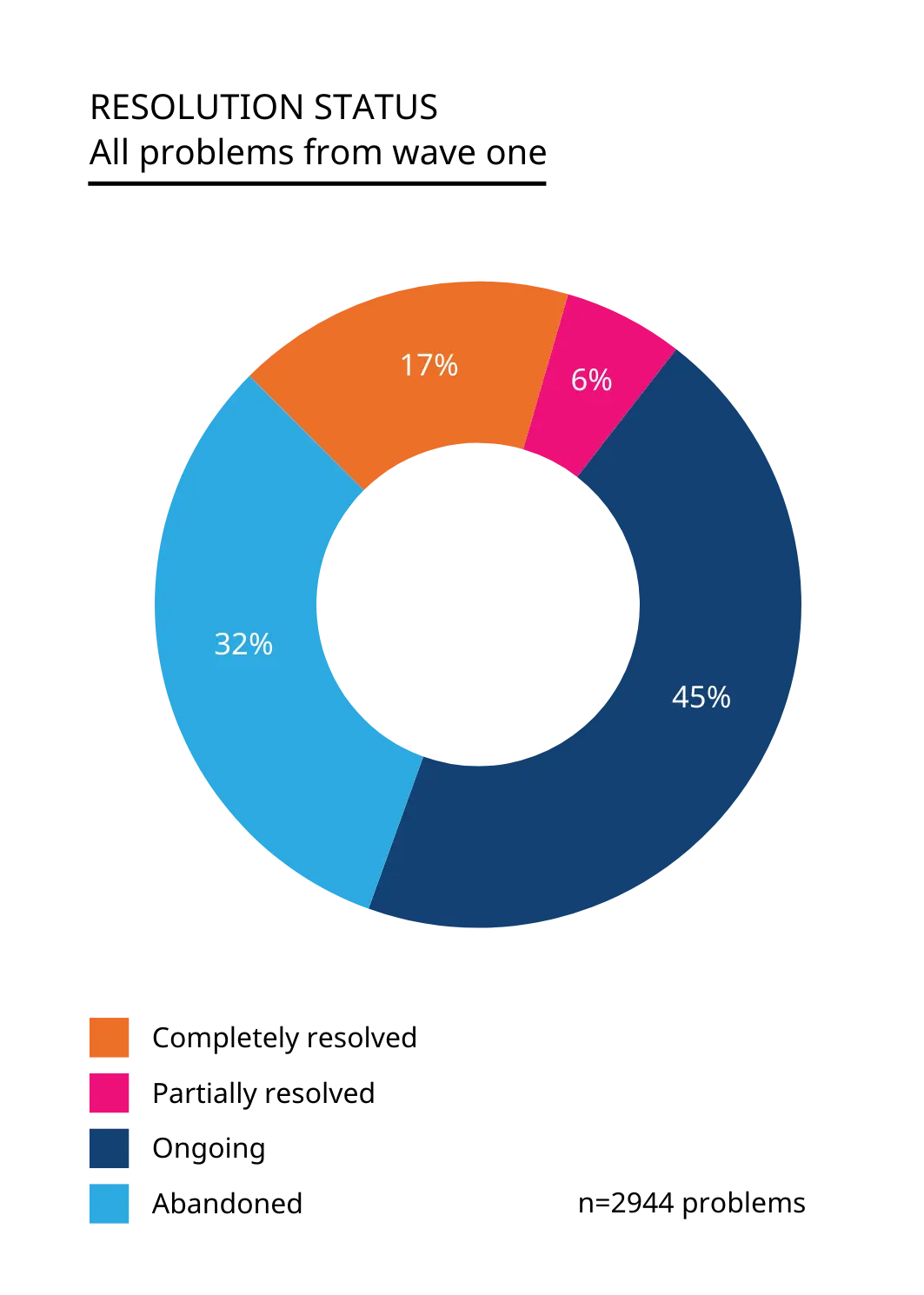

Around 45% of all legal problems were still in the process of being resolved, while 32% had been abandoned, meaning people either ceasing their efforts to find a resolution or never attempting to do so in the first place.

The number of unresolved and unfairly resolved problems together constitute the justice gap: The difference between the demand for justice and the actual justice people get. The number of ongoing problems could be seen as the current demand side of justice: These are the legal problems people for which people are still trying to find a fair resolution.

To understand the evolution of the justice gap and the demand for justice, the second wave of data collection looked at the following types of legal problems:

By measuring the current status of these three types of problems we can assess the justice landscape in Tunisia one year after publication of the JNS report and gain a deeper understanding of the nature and evolution of legal problems.

Almost half of the problems reported during the first wave of data collection were still in the process of being resolved at the time of the interview. During the second interview, we therefore asked people how these problems had evolved since the first time we spoke.

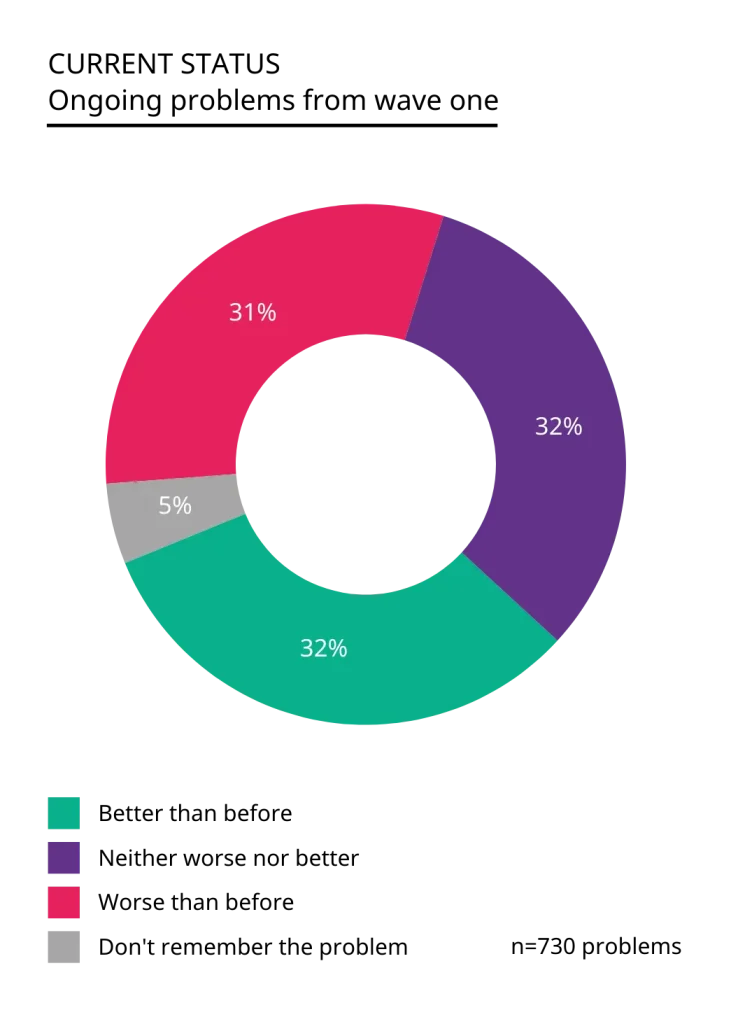

The current status of these ongoing problems is rather neatly divided between three statuses. In 32% of the cases, people felt that the situation had improved. In another 32% of the cases, the problem is considered neither worse nor better, while in 31% of the cases the situation has become worse than before. Only 4% of problems could not be remembered, mostly problems that were considered less serious at the first interview.

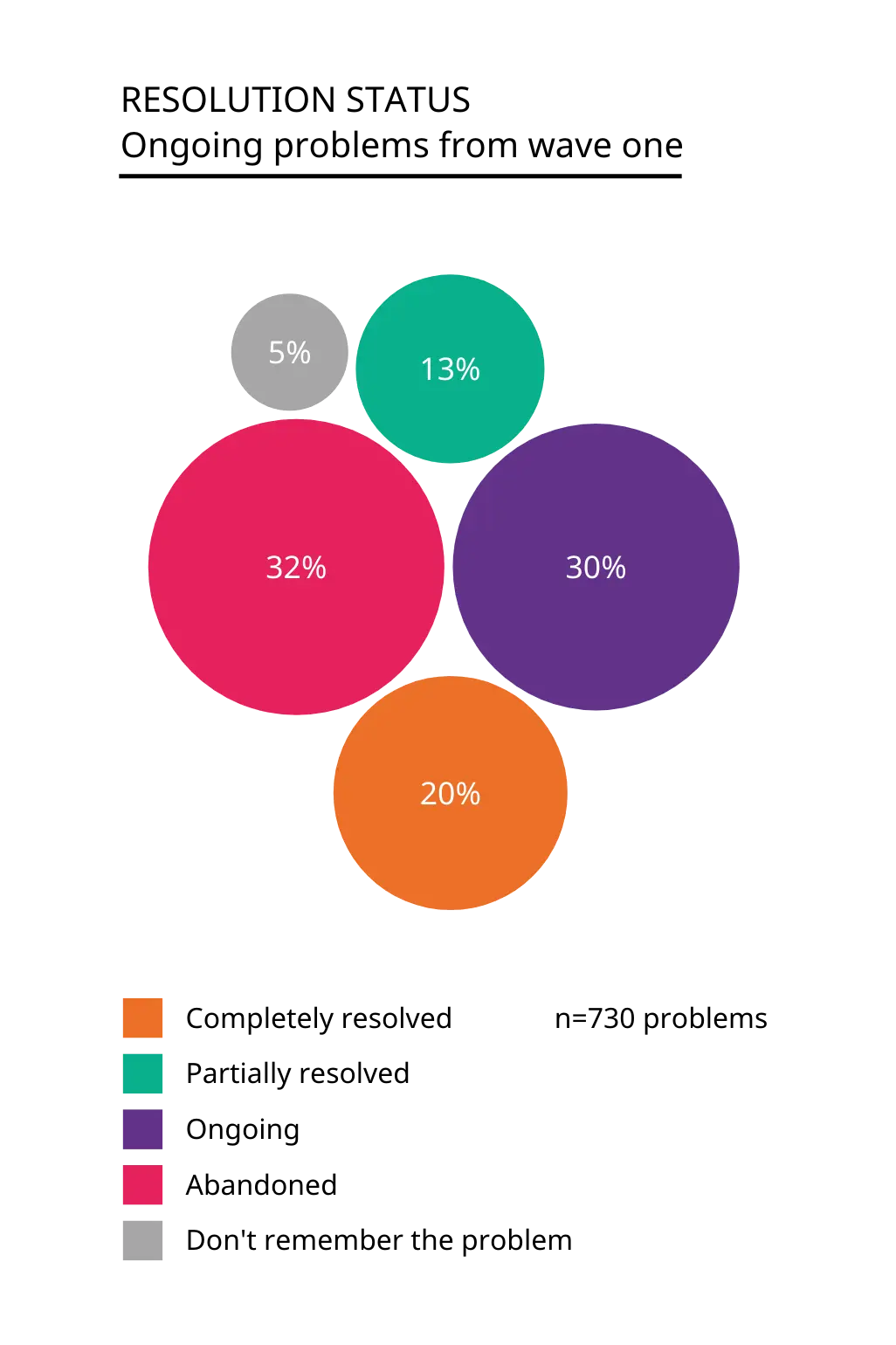

Not surprisingly, the majority of legal problems that are assessed as better than before, have been resolved in the meantime. More than a year after the first interview, around 20% of ongoing problems have been fully resolved and another 13% partially resolved. In other words, more than one out of three problems that were initially ongoing found a solution with time, narrowing the justice gap. It means around 39% of all legal problems from the first wave reached a solution within two years, a positive sign for the justice sector in Tunisia.

Around 30% of the ongoing problems from wave one were still in the process of being resolved at the time of the second interview. Even after more than one to two years, these people still are trying to find justice in order to be able to move on with their lives. These are some of the most serious problems people are dealing with, having long lasting negative effects on various aspects of their lives.

Finally, 32% of ongoing problems from wave one have been abandoned, adding to the 32% of problems that were already abandoned during the first interview. It means that almost half (47%) of all problems reported during wave one are eventually given up on without achieving any kind of resolution.

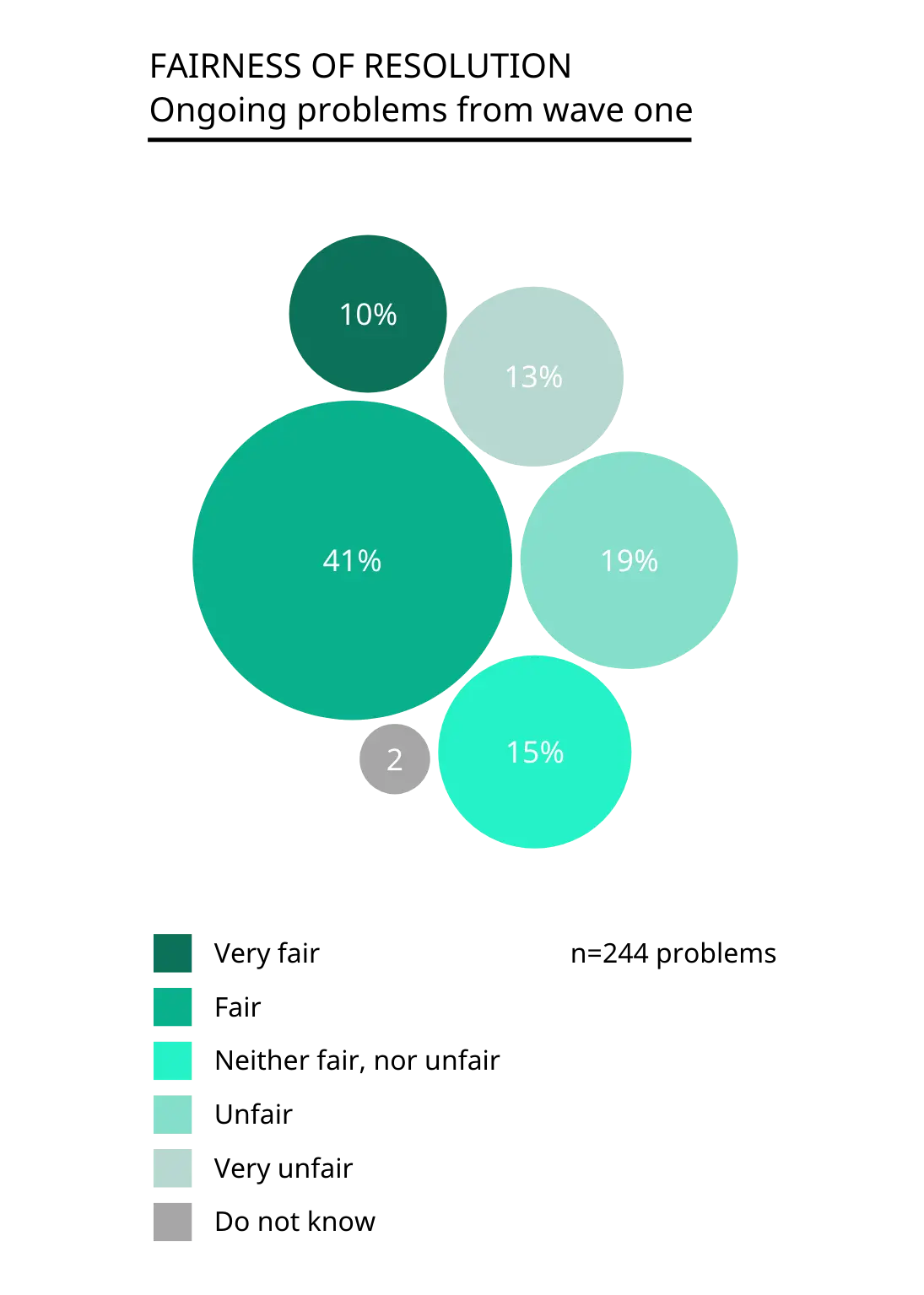

As we already found in the JNS Tunisia 2023, not all resolutions people receive are considered fair. Around 51% of the resolutions for ongoing problems from wave one are considered fair or very fair, a similar percentage to the resolutions discussed during wave one (48%).

Just like in the first interview, in the second interview we asked people what steps they took to try to resolve their most serious problem. For the most serious ongoing problems from wave one, around 75% had taken one or more actions to try to resolve the problem. Since the first interview, around 56% of people have taken one or more (additional) actions.

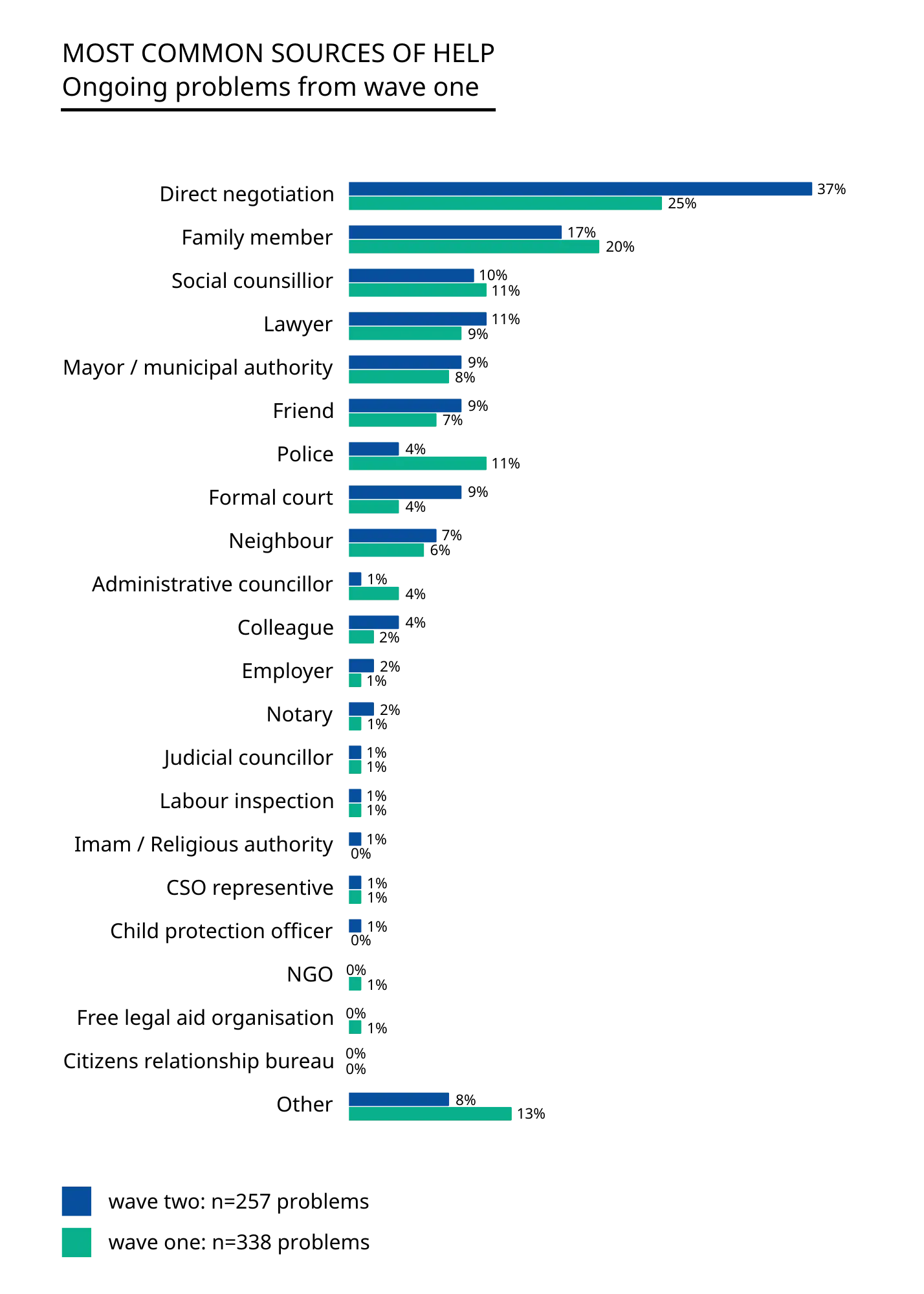

The graph below shows the sources of help people engage over time, looking at the most serious ongoing problems from wave one. Although the most common sources of help do not change much over time, there are still some interesting shifts. In particular, people tend to go to the police early on in the process (11% in wave one compared to only 4% in wave two), whereas people are more likely to go to a formal court as the problem drags on over time (4% in wave one compared to 9% in wave two). Despite this increase in people going to court when problems drag on for longer periods of time, it is still only a fraction of all legal problems.

Remarkably, a lot more people talked directly to the other party later on in the process (25% in wave one compared to 37% in wave two), even though it could be expected this is often the first step in the process.

More generally, and as already highlighted in the JNS Tunisia 2023, social networks play an important role with many people asking help from family members, friends, and neighbours. Beyond family members and social contacts, the most common sources of help are the police, social counsellors, lawyers, and local or municipal authorities.

The JNS Tunisia 2023 highlighted employment problems as not only some of the most common types of problems experienced by Tunisians (especially young people), but also as the problem category with a relatively high impact on people and very low resolution rate. Indeed, only 13% of employment problems were completely or partially considered, while 41% remained ongoing and 46% were abandoned. The latter percentage was among the highest of all problem categories. People also had very little recourse to effective sources of help, relying almost exclusively on family members and friends.

A year later, around 37% of the ongoing employment problems from wave one are still ongoing, meaning people are still trying to find fair resolutions. And while around 31% of problems are completely or partially resolved, 32% are abandoned, thus adding to the already high percentage of employment problems that are never fairly resolved.

Very few people took additional action since the first interview. Only 38% did take some form of action, but this was primarily talking directly to the other party or involving someone from their social network (colleague, family member, friend). It highlights the lack of meaningful justice pathways that exist for the many people dealing with employment disputes in Tunisia.

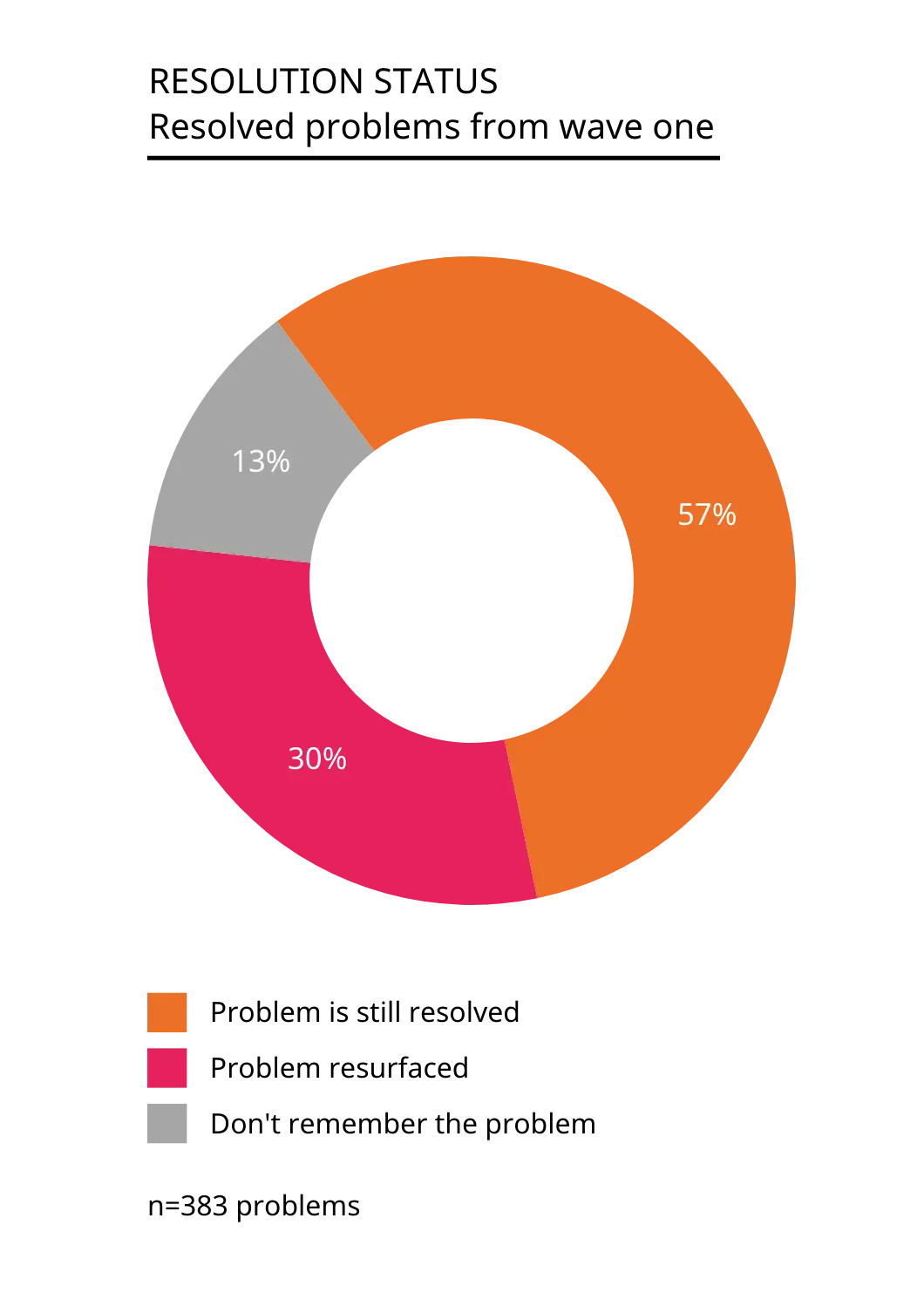

Around 23% of all problems reported in wave one were partially or completely resolved at that time. However, not all resolutions are created equal. Over a year later, around 57% of these problems are still considered resolved. At the same time, 30% of problems that were initially resolved resurfaced again in the following year, thus widening the justice gap. This constitutes around 7% of all legal problems reported in wave one. Around 14% of problems could not be remembered anymore, a much higher percentage than for the ongoing problems from wave one. As explained in the JNS Tunisia 2023, ongoing problems tend to be assessed as more serious than both abandoned and resolved problems, thus making it less likely that people forget about them.

This shows that legal problems are not static and resolutions can be temporary. While the justice gap is dynamic, the overall demand for justice remains relatively stable. The resolution of ongoing legal problems helps to narrow the justice gap with 16%, but resurfacing problems that were considered resolved in turn widen the justice gap with 7%. As we will show below, this is even before considering new problems that appeared since the first wave of the study.

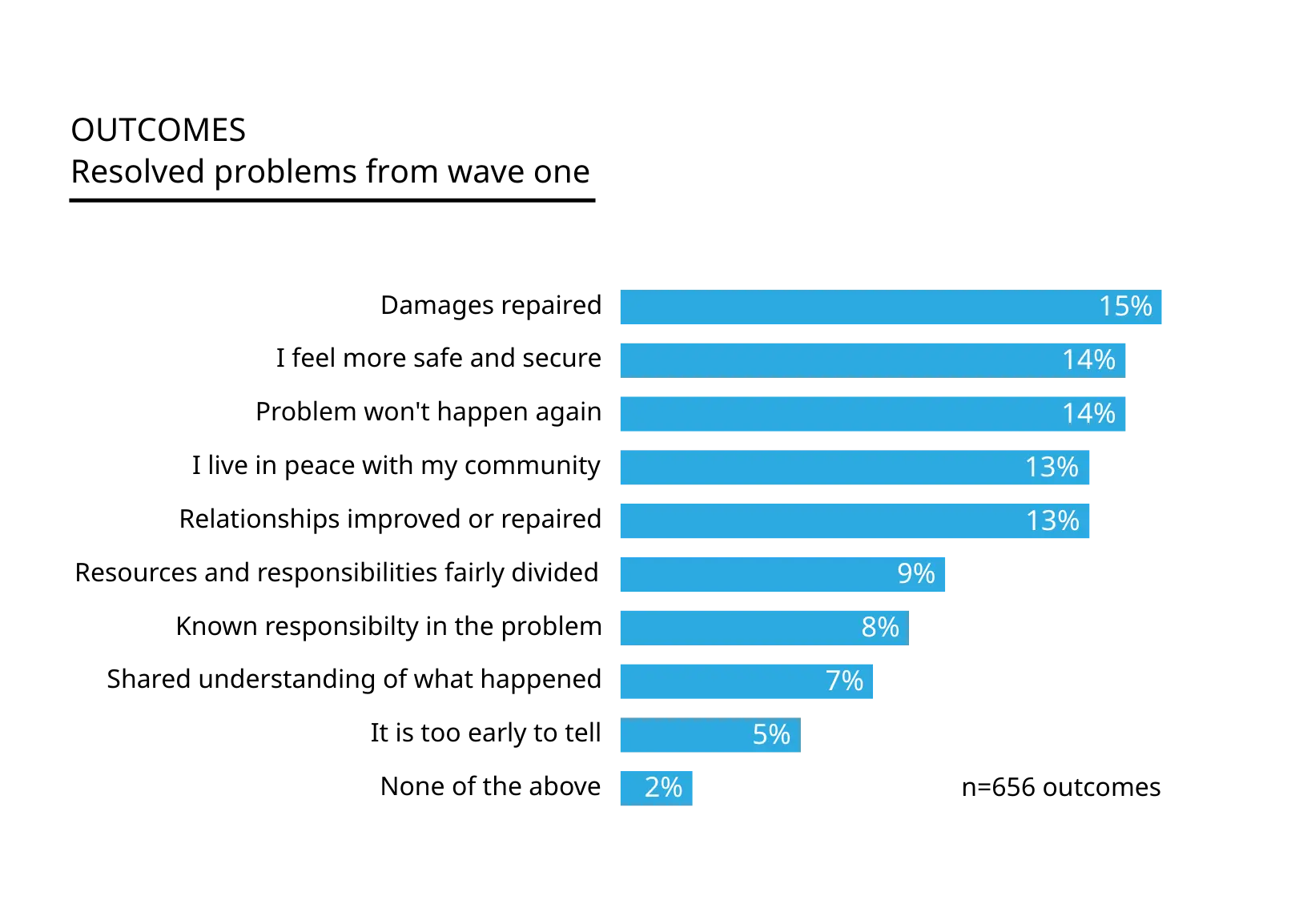

Resolution of legal problems is only one part of justice. Such resolutions ideally lead to positive outcomes in people’s lives. For every resolved problem from wave one that was still resolved during the second interview, we asked people about the outcomes beyond the resolution.

Almost everyone (92%) experiences one or more positive outcomes following the resolution of a legal problem. The outcomes people reported are rather diverse, without any of them really standing out. This is partly because the outcomes people seek and receive depend on the type of problem they experienced. However, the most common outcomes are either related to restoring the situation (damages repaired, relationships improved or repaired), having a sense of safety and peace (I feel more safe and secure, I live in peace with my community), and future prevention of the problem (problem won’t happen again). These provide important pointers for justice practitioners that seek to help people experiencing legal problems.

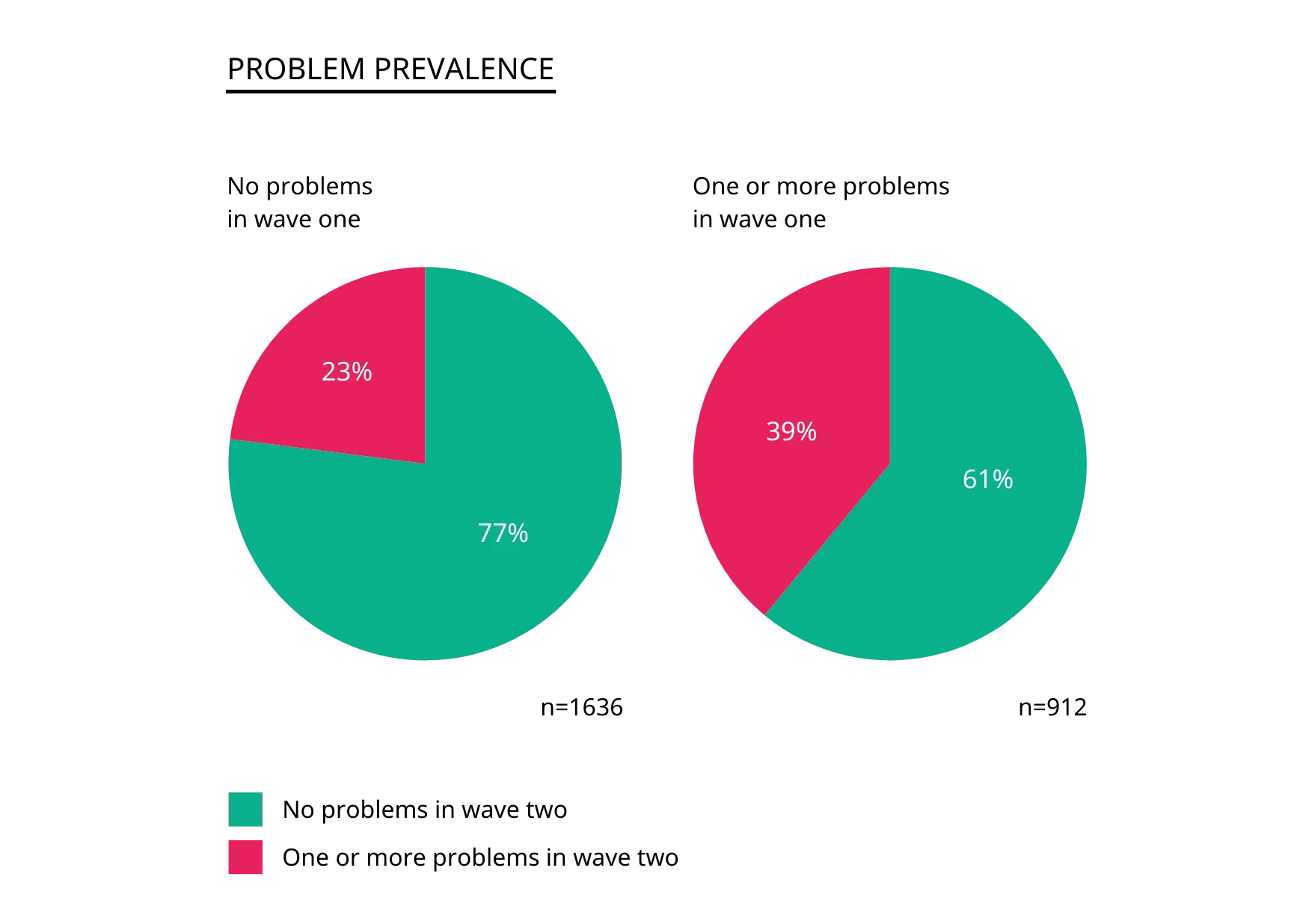

With ongoing problems getting resolved and resolved problems resurfacing, the justice gap in Tunisia is in constant flux. Another complication is the occurrence of new legal problems since wave one of the study. Around 28% of people experienced one or more new legal problems between the first and the second interview. On average they reported 1.8 problems per person. This is very similar to the findings in wave one of the study (31% of people experiencing on average 1.9 problems).

People who reported one or more legal problems during wave one are significantly more likely to report one or more new legal problems in wave two (77% versus 61%). In other words, it seems that experiencing legal problems increases the risk of subsequently experiencing more legal problems. Another explanation could be that certain people are more prone to experience legal problems than others.

The demographic differences are the same in wave two as in wave one. Men, younger people, people with a higher education level, and people with less financial means are significantly more likely to report one or more legal problems.

Around 23% of the people who did not report a legal problem during wave one did experience a legal problem in the subsequent year. This means that over a longer period of time even more people encounter legal problems than the 31% reported in the JNS Tunisia 2023. Over two waves, roughly 47% of people reported one or more legal problems.

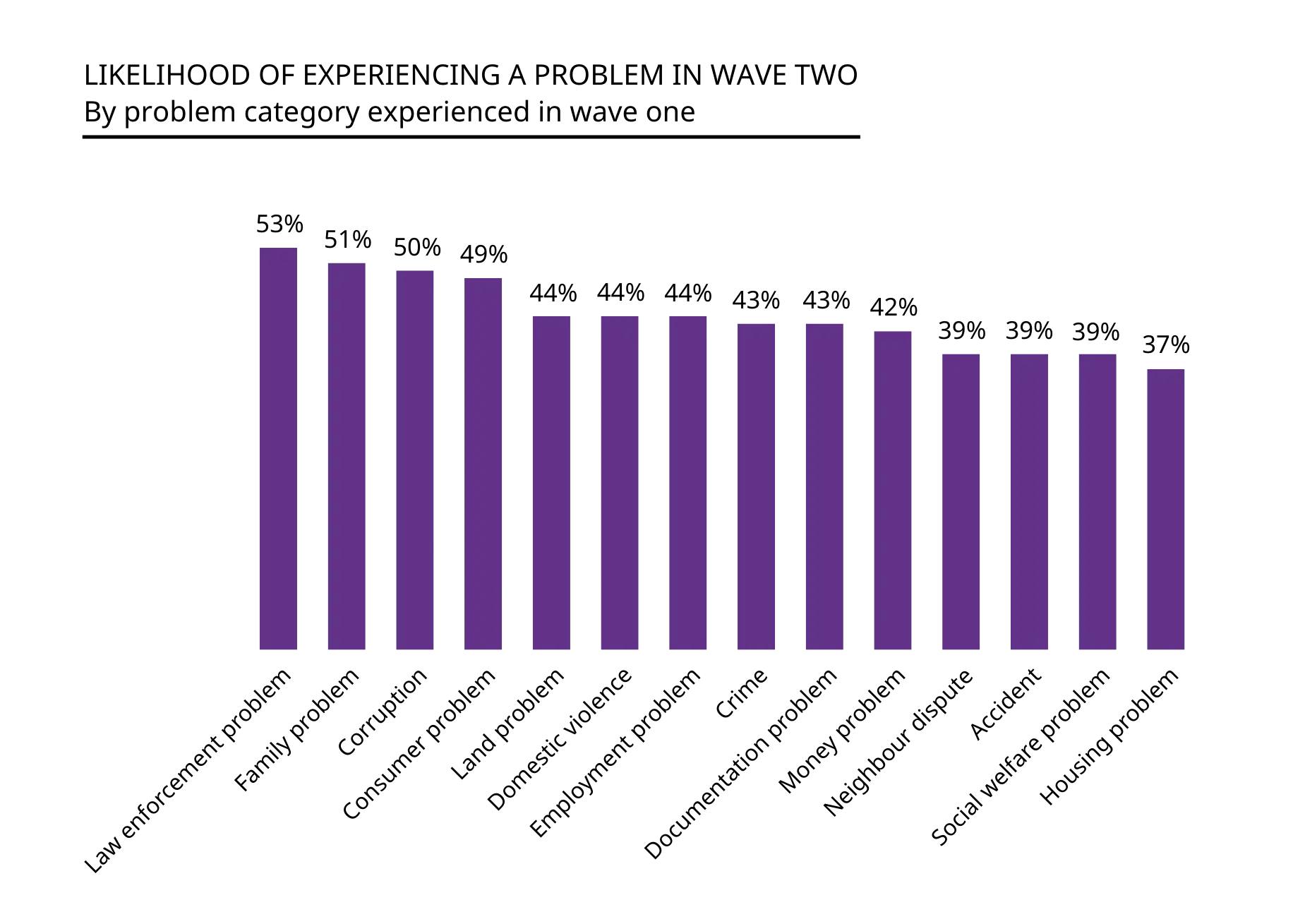

Split out by problem category, it is apparent that people experiencing certain problem categories are more likely to experience a legal problem in the following year. In particular, people experiencing a problem with law enforcement, a family problem, corruption, or a consumer problem in wave one of the study are more likely to also experience (either similar or completely different in nature) in wave two.

Some of these (law enforcement, corruption, consumer) are typical problem categories that not everyone easily identifies as legal problems. As such, one explanation for this could be more awareness among these people about the legal nature of certain problems they face.

When looking at the most common problem categories, there are some changes between the first wave and the second wave, although the overall tendencies are mostly similar. In particular, people report more problems related to social welfare and land problems in wave two, whereas they report fewer neighbour disputes and employment problems. These changes cannot be explained by the smaller sample size in the second wave of the study, but it could be the case that the mode of interviewing (over the phone instead of in person with a showcard listing the potential legal problems) has had some effect.

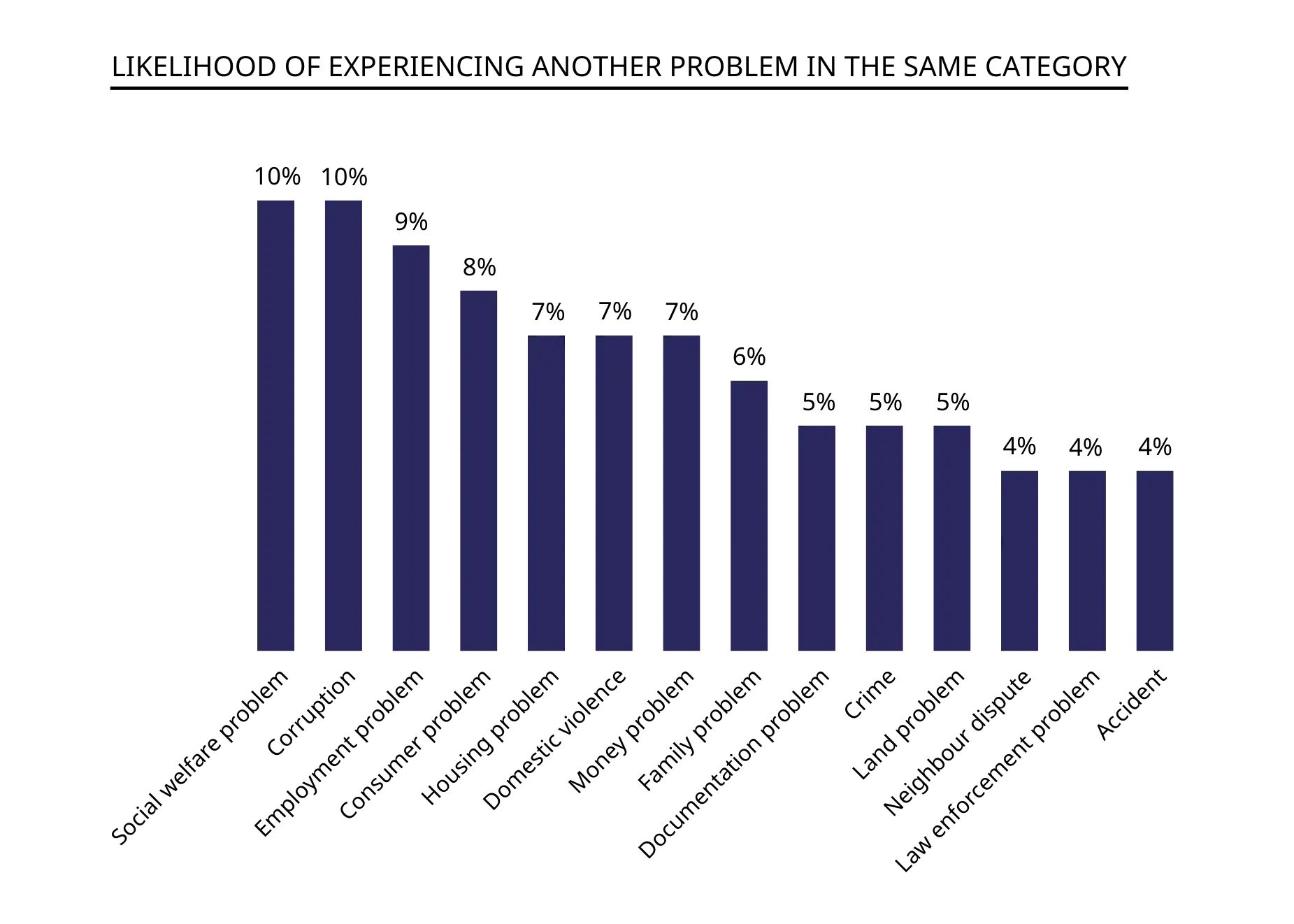

We also looked at how likely it is that people experienced similar legal problems as their most serious problem of the first interview. In other words, how likely is it that people experience land problems or neighbour disputes several times in a row? The data shows that people experiencing a problem in some of the most common categories are also most likely to experience a new problem in the same category.

Around 10% of people experiencing a social welfare problem end up experiencing another land problem within a year. It is the same percentage for people experiencing corruption. Employment problems and consumer problems also have a relatively high likelihood of leading to additional problems in the same category. To what extent these are entirely new problems or a resurfacing of old problems is often hard to distinguish, but it is clear that these problem categories have a high level of ‘stickiness’.

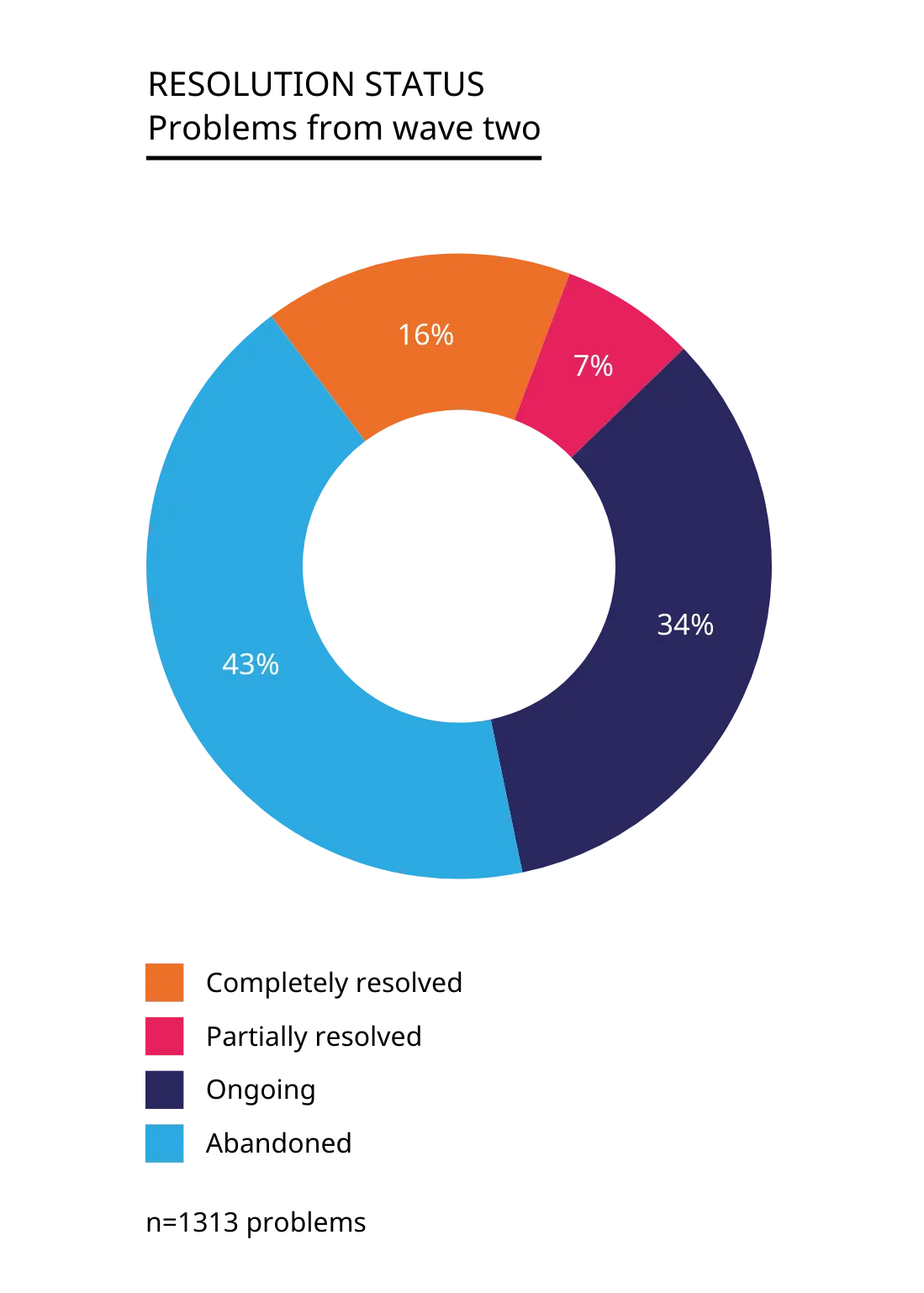

Around 23% of all legal problems reported in wave two are already completely or partially resolved at the time of the interview. This is the exact same percentage we found in wave one of the study. However, compared to problems reported in wave one, the problems reported in wave two are abandoned more often. No less than 43% of all problems have been given up on, compared to 32% in wave one. Around 34% of problems in wave two are ongoing, compared to 45% in wave one. This high level of abandoned problems is a significant challenge for the Tunisian justice system.

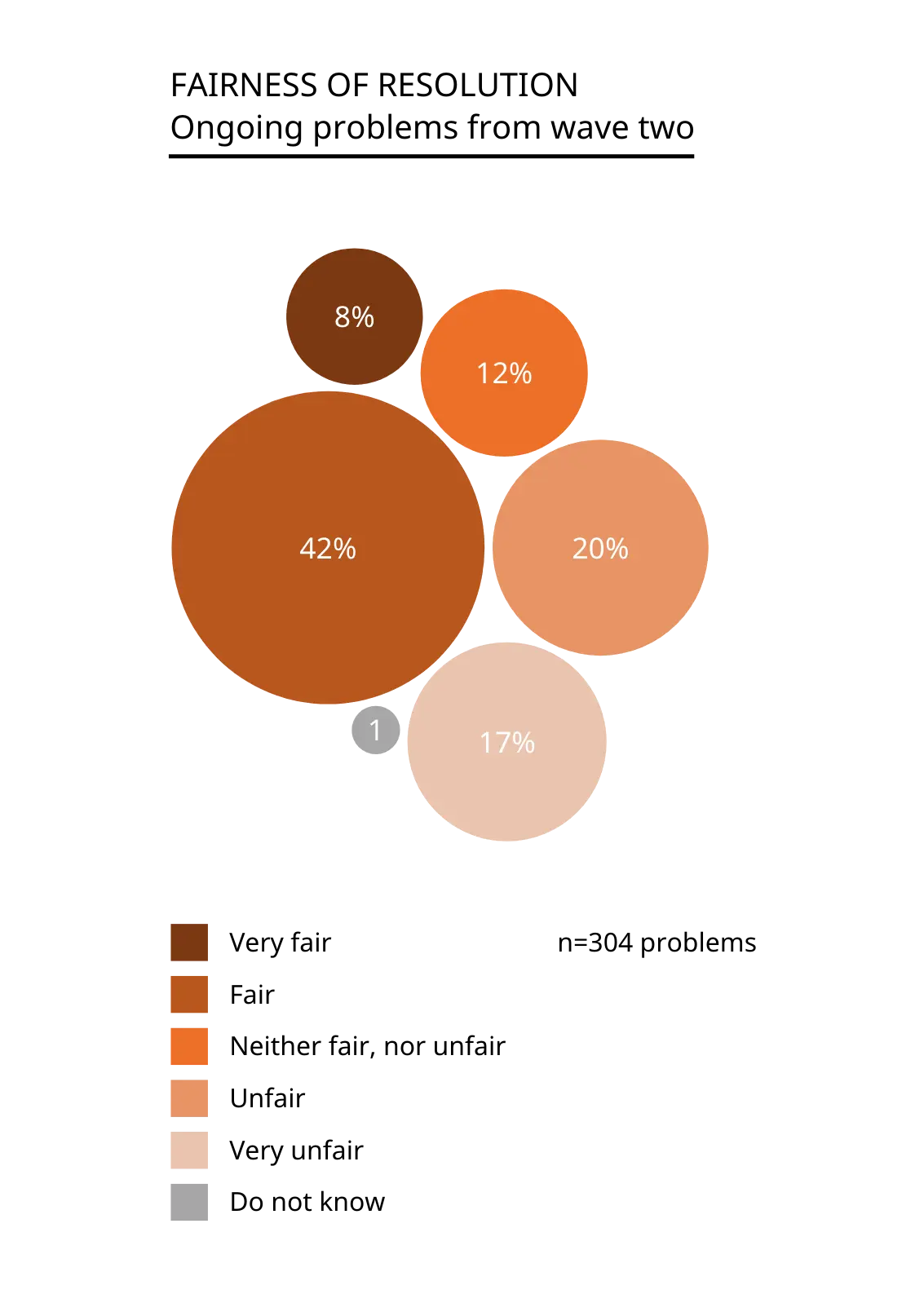

Similar to what we already found in wave one and ongoing problems that were resolved by wave two, around 50% of all resolutions are considered fair or very fair. This suggests that even if people manage to resolve their problem, many people are not satisfied with the outcomes they receive, even though they manage to resolve their problem.

Once again, the vast majority of these resolutions are assessed as fair or even very fair. It shows that people are generally satisfied with the resolutions they get, even though the majority of these are achieved outside the formal justice system.

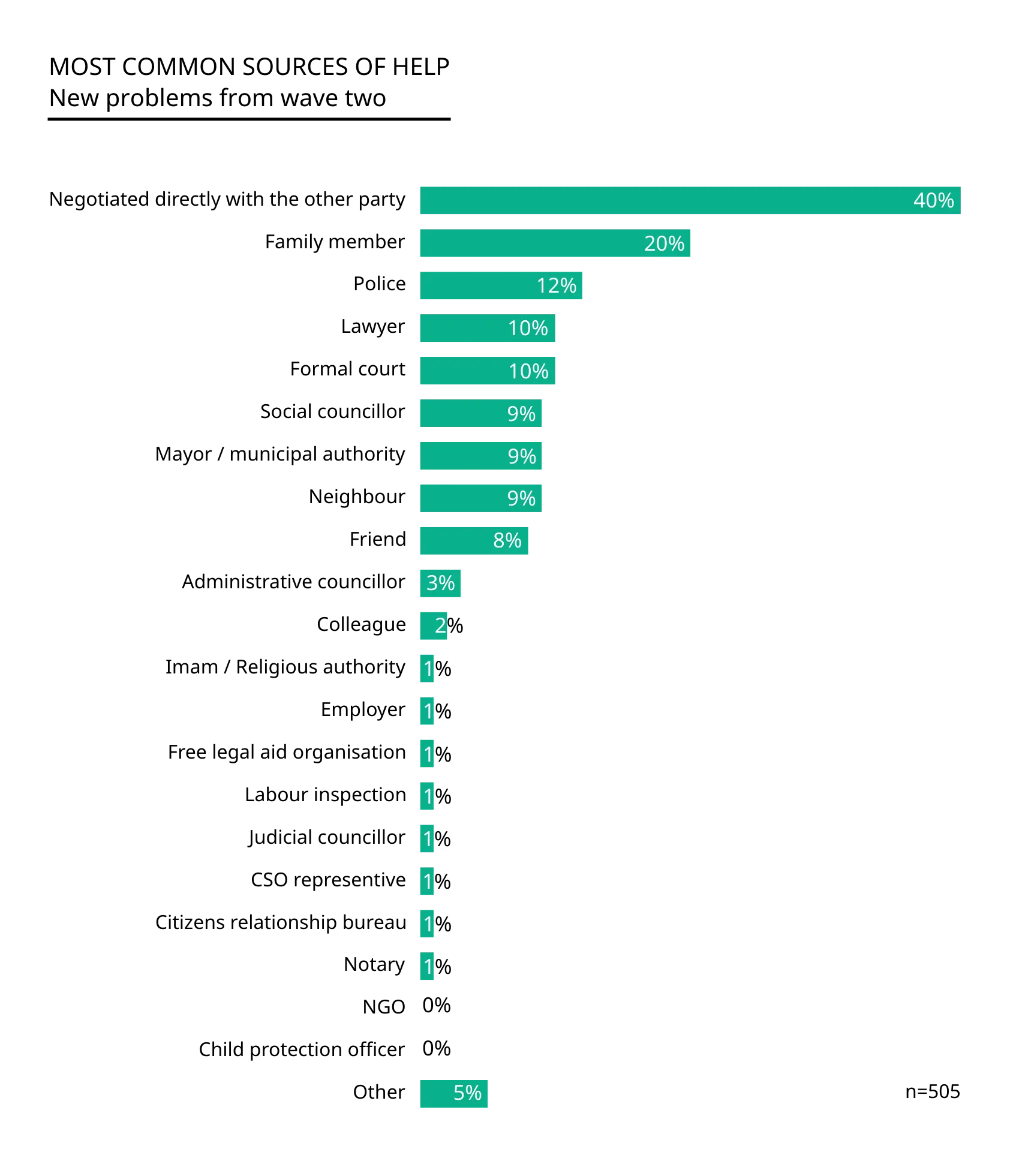

As usual, we asked people what they did to try to resolve the most serious problems they reported in wave two. Around 70% of people took one or more actions, the exact same percentage we found in wave one. The most common sources of help they engaged are also mostly very similar to our findings from the JNS Tunisia 2023.

The most common approach remains to talk directly to the other party in the dispute; compared to wave one, this percentage is even much higher. Social networks play an important role, especially family members and to a lesser extent friends and neighbours. Outside the personal network, the most important actors are the police, lawyers, and formal courts. Interestingly, the engagement of formal courts has significantly increased compared to wave one (from 4% to 10%). Social councillors and local or municipal authorities also remain relatively common sources of help.

The justice gap in Tunisia is large and dynamic. Many problems get resolved, although this sometimes takes a long time. But these solutions are not always permanent, as legal problems resurface again or people experience similar problems after a while. In the end, as legal problems keep accumulating, the demand for justice in Tunisia is relatively constant and remains high.

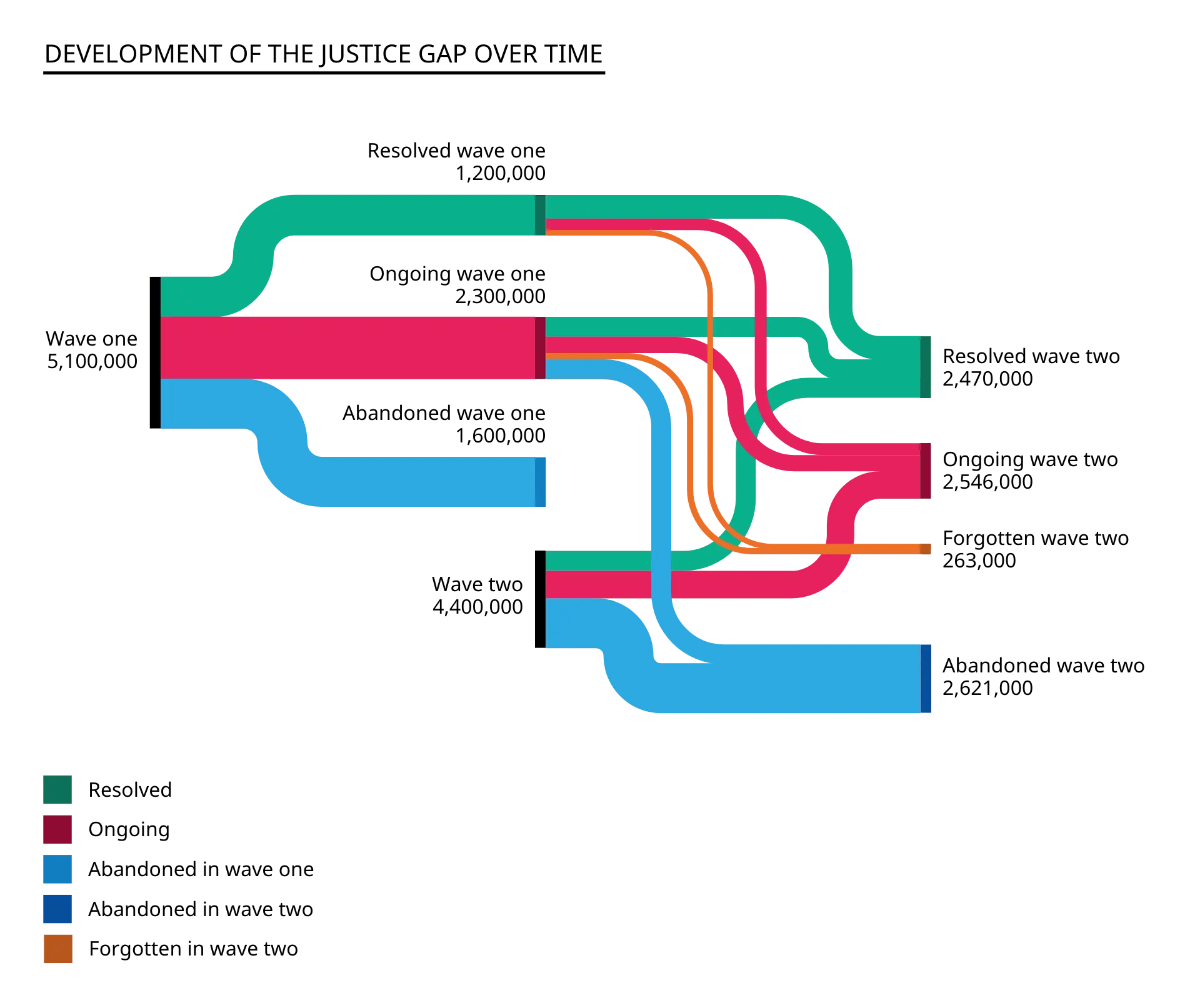

In the JNS Tunisia 2023 we estimated that around 2,3 million legal problems were ongoing (out of just over 5 million problems in total), with people still trying to find solutions. One year later, around 30% of these problems remain ongoing. This means almost 700,000 legal problems from wave one are still in need of a solution.

Besides these ongoing problems from wave one, around 30% of the 1,2 million legal problems that were considered resolved (or roughly 350,000 million legal problems) resurfaced again. Combining these two categories suggests over one million legal problems from wave one are still (or again) in need of a resolution one year later.

In the second wave of data collection, around 28% of people experienced on average 1.8 new legal problems. This means an estimated 4,4 million new problems happened in the last year. Whereas roughly 23% of these problems were quickly resolved, around 34% remained ongoing at the time of the interview. This means 1,5 million new legal problems from wave two are still in the process of being resolved.

Combining the ongoing problems from wave one and wave two results in an estimated 2,5 million legal legal problems that are in need of a solution. In other words, the demand for justice in Tunisia is relatively stable over time, remaining consistently very high. At the same time, a total of 4,3 million legal problems from wave one and wave two have been abandoned, while only 2,5 million problems have been resolved.

The graph below visualises the development of the justice gap over time. As older problems remain ongoing or resurface again, new legal problems also emerge in the meantime. The result is an accumulation of ongoing legal problems and a consistently high demand for justice, but an even higher level of abandoned problems. The justice system in Tunisia faces a big challenge ensuring that people are able to get their legal problems resolved and move on with their lives.

As we already highlighted in the JNS Tunisia 2023, there appears to be a gap of available justice services that address people’s legal problems. Besides the formal justice system and local authorities and social counsellors (for specific problem categories), there are relatively few affordable and accessible justice providers for Tunisians.

To address the large number of abandoned legal problems, support for innovative justice providers would be a crucial first step. Such innovations do not need to compete with the formal justice system, but would rather complement them, with strong potential for collaboration between private actors and the public sector.

The current justice system is failing too many Tunisians. In order to provide people with meaningful access to justice, it is key to invest in people-centred alternatives.

Table of Contents