Delivering Justice, Rigorously

A guide to people-centred justice programming

September, 2022

Explore Data of Countries

Find out how people in different countries around the world experience justice. What are the most serious problems people face? How are problems being resolved? Find out the answers to these and more.

*GP – general population; *HCs – host communities; IDPs* – internally displaced persons

Explore guidelines for solving and preventing justice problems. They recommend interventions, which can support lawyers, paralegals and other practitioners in their work.

Justice Services

Innovation is needed in the justice sector. What services are solving justice problems of people? Find out more about data on justice innovations.

The Gamechangers

The 7 most promising categories of justice innovations, that have the potential to increase access to justice for millions of people around the world.

Justice Innovation Labs

Explore solutions developed using design thinking methods for the justice needs of people in the Netherlands, Nigeria, Uganda and more.

Creating an enabling regulatory and financial framework where innovations and new justice services develop

Rules of procedure, public-private partnerships, creative sourcing of justice services, and new sources of revenue and investments can help in creating an enabling regulatory and financial framework.

Forming a committed coalition of leaders

A committed group of leaders can drive change and innovation in justice systems and support the creation of an enabling environment.

Problems

Find out how specific justice problems impact people, how their justice journeys look like, and more.

A guide to people-centred justice programming

September, 2022

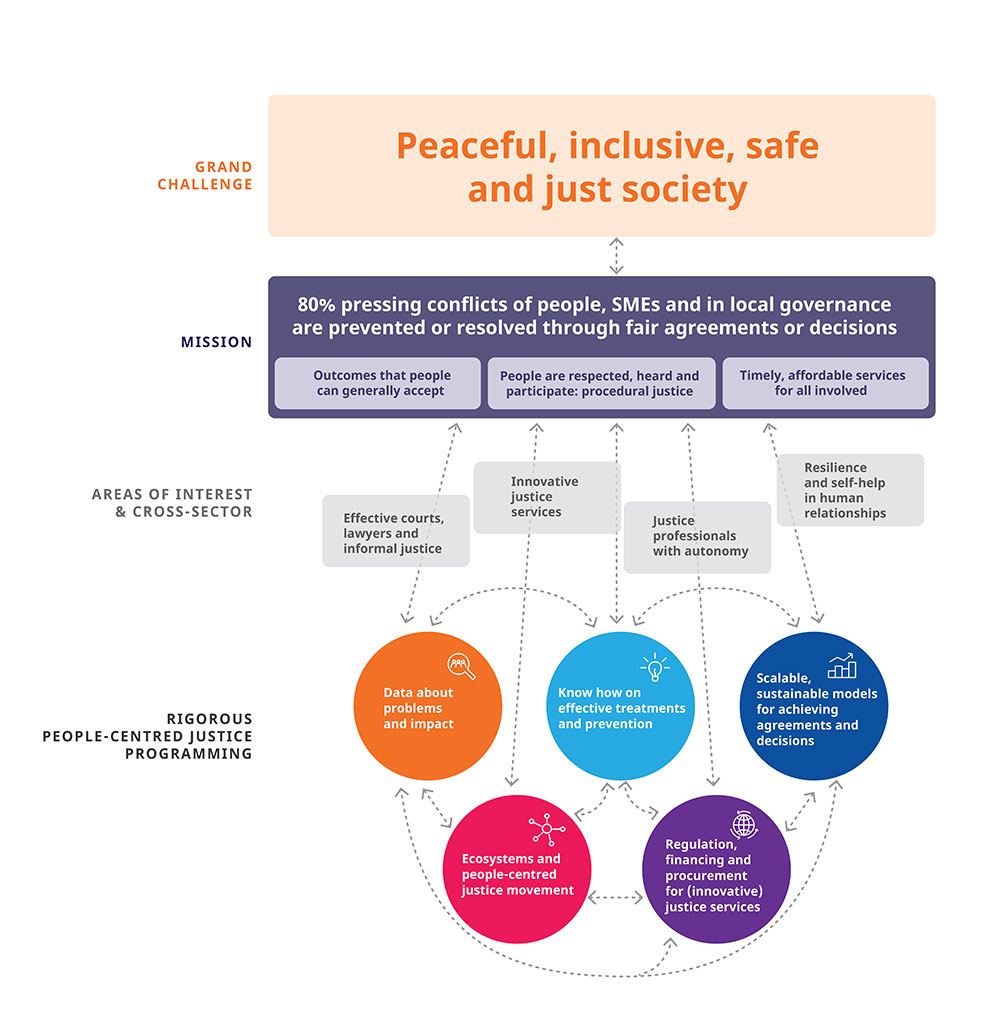

This report presents an evidence-based, people-centred approach to the delivery of justice. It aims to inform the work of a growing group of leaders who are responding systematically to the demand for fair, effective procedures that address populations’ dispute resolution needs. It builds on the work of many scholars, practitioners and committees who laid out the case for a pivot towards people-centred justice, both at the national and international level.

The report shows how a mission-oriented approach, led by an interdisciplinary task force, can spark overdue progress in how societies organise their justice systems to prevent and resolve conflicts. It explores how people-centred justice can be programmed, based on rigorous R&D and innovation. For each type of dispute, evidence-based prevention and resolution processes can be developed, tested and implemented, building on best practices and a growing body of interdisciplinary research.

Strategies to implement such systems are emerging. Pressing justice problems are being categorised and data on their resolution collected. Innovative justice interventions are being trialled and rolled out. This will improve the service delivery models of courts, law firms and government agencies and help them, as well as new players, to resolve conflicts in game-changing ways. It will also help us tackle the increasingly urgent tasks of strengthening social cohesion, reducing inequality and rebuilding trust in institutions.

The bottom line of this report is that societies need to find a way to take ownership of their systems for conflict resolution and prevention. The economic value of preventing and resolving conflicts is immense. Individual wellbeing and social cohesion are at stake.

We cannot sit back and expect that the current procedures and rule systems will respond to this demand. For reasons set out in this report, we see that the key players in the system itself – politicians, policy-makers, civil servants, judges, attorneys, journalists or village elders – are unable to do what is necessary, at least not at the scale and depth that is needed.

A dedicated, targeted, programming effort is needed to complement the good work of justice practitioners. In order to achieve the goal of peaceful inclusive societies, with equal access to justice for all (SDG 16), we should measure outcomes. Evidence about what works will help to prevent and solve many more conflicts in time. Promising justice services can reach far more people, anchoring public support and accountability. Incentive structures can be improved and better aligned with shared values. If conflict resolution thus becomes more effective, we are more likely to achieve almost everything that really matters.

HiiL’s mission is to ensure that the most pressing justice problems can be prevented or resolved at scale. This report is based on the belief that a task force can lead the efforts of a particular country or tackle a particular type of justice problem. In Chapters 1-3 it explains how such a task force could make the case for people-centred justice, be constituted, and set an agenda. Chapters 4-7 summarise HiiL’s investigation into the R&D and innovation needed to achieve this mission. Chapter 8 explains why a broad movement is needed to make this happen.

The report is based on the insights, methods and tools that have been developed in the sector – including HiiL’s contributions to this body of knowledge – and on experiences acquired during our work with justice leaders, courts of law and legal assistance organisations. A literature review was undertaken for each chapter. Our experience is based on work in Africa and the MENA region, and in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Ukraine, the United States of America, Canada and western Europe. The organisations HiiL works with help people who lack access to justice. Our experience has shown how legal assistance organisations have to cooperate in a structured way with law firms, courts, the police and government bodies to deliver more effective justice.

Our Justice Needs and Satisfaction survey has been undertaken in 19 countries. Unlike other legal needs survey methods, our method emphasises the outcomes people achieve for their problems (HiiL no date.-a). Based on the survey data, literature and trends, we have investigated which types of processes, agreements and decisions are most likely to prevent or resolve justice problems (HiiL 2018). We have developed a series of tools to support evidence-based resolutions and the prevention of justice problems — including 15 building blocks for prevention/resolution and a method for guideline development adapted from the health care sector based in which we developed 45 recommendations for the top five justice problems (HiiL n.d.-b; HiiL n.d.-c; HiiL n.d.-d). At present, we are working with justice practitioners on templates to implement evidence-based practices and standards to monitor outcomes.

The Accelerator unit for justice innovators has allowed HiiL to stay close to the realities and experiences of more than one hundred justice startups over the past six years (HiiL n.d.-e). Why did they succeed or fail? What do they and their funders need? In the Charging for justice trend report, HiiL (2020) summarised the main barriers and enablers to delivering effective resolution for justice problems. Our coaching with startups identified seven service delivery models or ‘gamechangers’ for justice services with potential for scaling (HiiL n.d.-f). At present, we are investigating the critical success factors for these gamechangers and models to finance them sustainably through contributions from parties to conflicts, the community and taxpayers (HiiL 2022d).

Through our programmes, HiiL has found that the regulatory environment of courts and legal services makes evidence-based work and scalable and sustainable services difficult to operationalise. In its report, Charging for Justice, HiiL (2020) investigated how the financial and regulatory environment can be improved. In parallel, we also started to design step-by-step strategies to overcome such barriers.

These strategies benefit from intensive dialogue and project cooperation with colleagues and experts working on UN SDG 16.3, which promises “equal access to justice for all.” The OECD, Pathfinders for Justice, USAID and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands are leading efforts to develop people-centred justice approaches OECD 2021; Pathfinders 2019; USAID 2022; Government of Netherlands 2022). In countries where HiiL has organised stakeholder dialogues and innovation labs, chief justices, court leaders, NGO directors and ministers have shared their visions. Experts from the World Justice Project, IAALS, the American Bar Foundation, UNHCR, OGP, UNDP and the World Bank are interacting with a growing group of university researchers focusing on responsive, human-centred design and evaluating innovative programmes (World Justice Project n.d.-a; Montague 2022; American Bar Association 2022; UNHCR 2018; UNDP and Australian Development Cooperation 2016; Open Government Partnership 2018).

HiiL is based in The Hague, the international city of peace and justice, where many of these interactions take place and where the city government is supporting R&D and innovation to service the population more effectively.

To support this growing movement, HiiL has developed early prototypes to quantify the contribution of programmes to SDG 16.3, national GDP and people’s wellbeing. In several countries, we are interacting with national planning agencies and with the leaders of the justice sector to develop a national people-centred justice programme.

On 20 April 2022, a dialogue between justice leaders from Kenya, Netherlands, Nigeria, Tunisia, Uganda and the United States of America compared notes on people-centred justice programming. The benefits of and impediments to evidence-based work were discussed. The annex to this report summarises this dialogue.

American Bar Foundation, (2020). ABF access to justice research network members. URL: https://www.americanbarfoundation.org/research/summary/1057. Accessed on July 18, 2022.

Government of Netherlands, (2022). The Hague is setting the stage for global justice.

HiiL, (2018). Understanding justice needs:The elephant in the room.

HiiL, (2020). Charging for justice: SDG 16.3 Trend Report 2020. HiiL.

HiiL, (2022). Game-changing factors that improve innovation in justice delivery.

HiiL, (n.d.-a). Collecting data on justice needs. URL: https://www.hiil.org/what-we-do/measuring-justice/. Accessed on July 7, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-b). Building blocks. Justice Dashboard. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/building-blocks/. Accessed on July 7, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-c). Guideline method. Justice Dashboard. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/treatment-guidelines/guideline-method/. Accessed on July 7, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-d). Guidelines for justice problems. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/treatment-guidelines. Accessed on July 7, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-e). Justice innovators. URL: https://www.hiil.org/what-we-do/the-justice-accelerator/innovators/. Accessed on July 7, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-f). The gamechangers. Justice Dashboard. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/the-gamechangers. Accessed on July 18, 2020.

Montague, K. (2022). IAALS launches allied legal professionals in an effort to increase access to quality legal services and help reduce barriers to representation. IAALS.

Nazifa Alizada, Rowan Cole, Lisa Gastaldi, Sandra Grahn, Sebastian Hellmeier, Palina Kolvani, Jean Lachapelle, Anna Lührmann, Seraphine F. Maerz, Shreeya Pillai, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2021. Autocratization Turns Viral. Democracy Report 2021. University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute.

OECD, (2021), OECD framework and good practice principles for people-centred justice, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Open Government Partnership, (2018). Opening justice: Access to justice, open judiciaries, and legal empowerment through the Open Government Partnership. Publisher: Open Government Partnership.

Pathfinders, (2019). Task Force on Justice, Justice for All – Final Report. (New York: Centre on International Cooperation, 2019).

UNDP and Australian Development Cooperation, (2016).Equal access to justice through enabling environment for vulnerable groups.

UNHCR, (2018). Toward Durable Solutions: Legal aid & legal awareness Factsheet January – December 2021.

USAID, (2022). USAID rule of law policy: A renewed commitment to justice, rights and security for all.

World Justice Project, (2021). Rule of law index. Publisher: World Justice Project.

World Justice Project, (n.d). Rule of law research consortium. URL: https://worldjusticeproject.org/our-work/research-scholarship/rule-law-research-consortium. Access on July 18, 2022.

Table of Contents

The Justice Dashboard is powered by HiiL. We deliver user-friendly justice. For information about our work, please visit www.hiil.org

The Hague Institute for

Innovation of Law

Tel: +31 70 762 0700

E-mail: [email protected]