How should a task force evaluate the value added by these services? Most of these services fixate on price. By increasing efficiency, they lower the costs of legal services.

A task force should consider outcomes first. Information or advice is valuable if it increases resolution rates. Finding a lawyer prepared to take on a case does not help, unless that lawyer is more capable than a random lawyer found on the web in negotiating good outcomes for clients. Help with filing a claim at court is as good a value proposition as the solution the court offers. If the service is not capable of delivering good outcomes, price hardly matters. It is like lowering the price of diesel generators to ensure people get power 24/7. Actually, surveys on access to justice indicate that price is only one of many barriers to effective solutions. In our 2020 Trend Report Charging for Justice we explored the option that fixating on price may even decrease access to justice. If customers can only distinguish between services according to price and are not able to assess the value services bring to them, providers will compete on price and quality will decrease in the entire market.

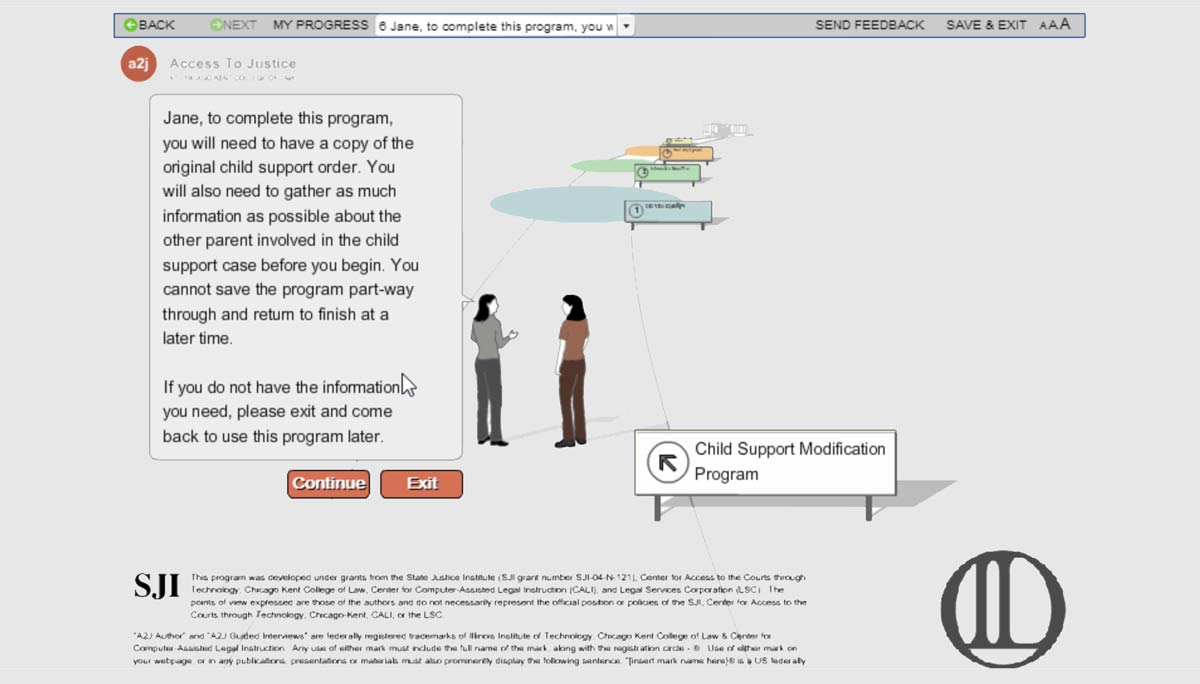

In order to prepare providers of these services for substantial investments, we therefore recommend a taskforce to ask them to first define outcomes. Then stimulate them to ensure these outcomes can be achieved. Evidence for this may be made available by developing a treatment guideline or using an existing one. Next, the service can be standardised to ensure outcomes in a systematic way. Ideally, the service offers the users a step by step process towards resolution, with continuous evaluation of progress against the desirable outcomes.