Community Justice Services Policy Brief

Building on the merits of informal justice and alternative dispute resolution processes, many countries have developed community justice or informal justice programmes. Although informal justice processes come in many different forms, they tend to have a participatory nature, strive for consensus, focus on social harmony and promote restorative (conciliatory) solutions.

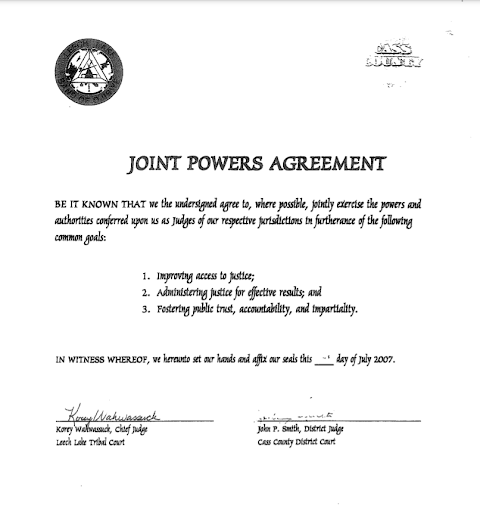

Case: Tribal-State Joint Jurisdiction Wellness Courts

CASE Tribal-State Joint Jurisdiction Wellness Courts Download Photo by WellnesscourtsCommunity Justice Services – Policy Brief / Case: Tribal-State Joint Jurisdiction Wellness Courts The above reproduced Joint Powers Agreement between the Leech Lake Tribal Court and the Cass County District Court is reproduced from Cass County Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe Wellness Court: From Common Goals […]

Case: Houses of Justice

CASE Houses of Justice Download Photo by Casa de JusticiaCommunity Justice Services – Policy Brief / Case: Houses of Justice Key fact and figures Year of establishment 1995 Scope of service/ Type of justice problems addressed Family, neighbour, crime, money, public services Geographical scope Country-wide (Colombia) – partial coverage Legal entity Part of the government […]

Case: Bataka Court Model

CASE Bataka Court Model Download Photo by Bataka Court Community Justice Services – Policy Brief / Case: Bataka Court Model Key fact and figures Year of establishment 2014 Scope of service Civil justice problems and petty crime Geographical scope 2 districts in Uganda Legal entity Privately run foundation Type of justice problems addressed: Civil justice […]

Case: Sierra Leone Legal Aid Board

CASE Sierra Leone Legal Aid Board Download Photo by Legal Aid Board Sierra Leone Community Justice Services – Policy Brief / Case: Sierra Leone Legal Aid Board Key fact and figures Year of establishment 2015 Scope of service Legal representation, advice and education Geographical scope Country wide Legal entity Government created institution Type of justice […]