3

3. Agenda-setting: pressing problems, goals and gamechangers

Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / 3. Agenda-setting: pressing problems, goals and gamechangers

In this chapter we explore how task forces can scope their work. They may be assigned a specific type of justice problem. They may also be expected to improve access to justice for all civil justice problems, for example, or to improve access to justice in general. Connected to this, they may select a particular type of justice service delivery model that they set out to implement in the country.

Before zooming in on a direction for a solution, a task force may want to take the time to jointly internalise lessons learned. Justice innovation has often failed. We listed a number of common justice innovation traps, detailing the reasons why they should be avoided.

During this process, task force members develop a joint understanding of the level of reform they are going to pursue. Task forces can generally be expected to focus on renewing and eventually replacing current services, rather than upgrading them.

Prioritising justice problems

Surveys of justice needs provide data on the most pressing justice problems. Task force members may want to connect to these needs by sharing personal stories of injustice. In the stakeholder dialogues that HiiL facilitates, lived experiences of people and data complement each other.

In this way, task force members are reminded that the most pressing justice problems are related to the satisfaction of core human needs. One of these core needs is to forge and maintain good family ties, even in times of hardship. Another is positive and empowering work that provides an adequate income. Access to land and housing are core needs as well and quality of life in communities requires good relationships with neighbours. Businesses need certainty on how they can invest and the environmental impact of activities needs to be minimised.

These core human needs are at stake when families separate, workers sent home, tenants evicted, and when neighbours become a source of noise, irritation or trash. People also want access to essential government services: health care, water, electricity and education. Debt relief and social benefits protect against poverty. People want to be safe from crime and violence, and to be protected against accidents.

Task forces can set priorities in a rigorous way. Although quantifying impact is not straightforward, justice problems can be ranked according to frequency and severity.

We recommend that task force members establish the resolution capacity needed based on the number and severity of problems that occur each year. The numbers in the graph found in Chapter 1 give an idea of the capacity needed by a country to prevent and resolve its most pressing justice problems. These estimates can be adjusted based on a country’s size. More precise numbers can be obtained from a legal needs survey or from administrative data (if all relevant problems of that type are recorded by a government agency).

Setting goals, indicators and targets

Task forces typically select either a problem type to work on, or up to five of the most pressing problem types. They may then set goals. One goal may be to prevent domestic violence in a country, or to resolve land conflicts efficiently and effectively. Clear goals, expressed in outcomes for people, enable task forces to assess whether the programme implementation has been successful.

Some programmes have multiple goals and that can be confusing for implementers. Houses of justice in Colombia (see annex of this report) aim to increase the efficiency of existing services, to extend the reach of government in low-income neighbourhoods and rural areas, and to expand access to justice. These goals may need to be aligned and rephrased as outcomes for people, in accordance with emerging best practices. In HiiL programmes, we advise stakeholders to phrase objectives in a SMART way: specific, measurable, assignable, realistic and time-related (Doran 1981).

A goal directly linked to the challenge addressed in this report, for example, would be to develop the capabilities and methods to resolve or prevent the most pressing conflicts in an evidence-based and people-centred way.

Measuring progress towards a goal requires indicators. Indicators for conflict resolution can be defined in several ways. The indicator for SDG 16.3 proposed by the UN is the “number of persons who experienced a dispute during the past two years who accessed a formal or informal dispute resolution mechanism, as a percentage of all those who experienced a dispute in the past two years, by type of mechanism.” This indicator focuses on accessibility to existing institutions. In the people-centred justice approach, outcomes for people are key, so resolution rates for problems can be a good indicator. A task force may also decide to take into account the fairness or effectiveness of solutions. One way to operationalise this is to quantify the problems reported in surveys as fairly resolved and add that to the number of problems that respondents consider on track towards a fair resolution, because some problems will still be in progress at the moment the results are measured.

In a programme developed for the Netherlands, HiiL proposed the following indicator: “the percentage of pressing justice problems resolved by a decision or agreement that is evaluated as fair by the disputants.” This information is available from the legal needs survey data that are collected every four years in the Netherlands. Selecting meaningful indicators is crucial. Mediation programmes are expected to have a high rate of settlement. This indicator is also increasingly used by courts. The rate of settlement needs to be combined, however, with an indicator that captures the quality of the resolution.

Disposition times are another indicator commonly used by courts. The number of months it takes from filing a case to the date judgement is rendered can be easily monitored. In Russia, the justices of the peace must decide cases within two months and are reported to be mostly successful in doing so (Hendley 2017). Here again, another indicator may be needed to reflect whether the court’s intervention was helpful. Moreover, disposition time indicators do not include the time between the emergence of a problem and the filing of a case in court. People-centred surveys therefore tend to ask about the time between the emergence of a problem and its resolution.

Recidivism is an indicator that should be used carefully. It measures whether someone who has committed a crime is again arrested or convicted. Data suggests that a second arrest is more likely to be for a minor offence. On the other hand, domestic violence may occur repeatedly before it is reported to the police. Moreover, recidivism measures seek prevention rather than resolution. They are unrelated to whether a victim has received restorative justice and only weakly related to whether community harmony is restored.

Task forces should think twice before selecting indicators related to inputs. Ministries often set targets for the number of policemen in the street or for the number of judges, for example. Sometimes budgets for legal aid or for courts are presented as indicators in policy documents. Research has shown that increases in budgets are not necessarily associated with better outcomes for people.

Once indicators have been established, targets can be set. Fair resolution rates for high-impact problems currently hover around 30%. Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) programmes often report resolution rates of 50% or higher. Task force members can investigate these rates and assess whether increasing the resolution rate to – for instance – 55% in two years and to 70% in four years could be a target. For the Dutch programme, we proposed a target of 80% for resolving pressing conflicts by a decision or agreement considered as fair by the disputant. The indicator in 2019 stood at 32% . The percentage of problems resolved by the decision of an authority or by agreement between the parties is at 39% (5% decision, 34% agreement). In the past, it has been as high as 60%. When a decision or agreement is achieved, Dutch citizens tend to accept them as fair (73% for decisions, 84% for agreements). The 80% indicator is thus ambitious, but seems achievable via rigorous R&D and innovation efforts.

View Additional Information

- The World Justice Project has proposed a number of civil justice indicators.

- The Council of Europe European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) collects data on court disposition times and various other indicators.

- For criminal justice indicators, see International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy (2015), Justice Indicators and Criminal Justice Reform a Reference Tool.

Selecting strategies

When setting targets, task force members will have strategies in mind to achieve them. A strategy is a route to meeting the goal, taking into account existing and foreseeable contexts, and the available capacity and resources. There may be more than one strategy towards a goal. Elements of strategies the task force might consider include improvements in treatment and service delivery through potentially game-changing models, or improvements to the enabling environment.

Stakeholders may start by discussing who will provide new interventions and the treatment of justice problems; they may launch game-changing services, or be responsible for improvements. Early discussions may bring competing interests of agencies and service providers to the fore, which can hinder progress. At this crucial moment, the task force should remain focused on achieving the best possible outcomes for people. What are the best processes for resolving the problem(s) identified by the task force? What is the best model for service delivery? Dialogue and R&D about this should be undertaken independently from “who” delivers the treatments or is best capable of offering a game-changing service. Who will be responsible should be decided when assessing the available and needed capabilities. Ideally, this will be decided on a level playing field by an independent assessor.

Strategies can be tested in relation to the goals and targets. What share of the population will the game-changing service reach? What increase in the resolution rate is expected once a new treatment has been implemented? What are the political push and pull factors that will negatively or positively impact the implementation of a particular improvement?

In projects HiiL has participated in, task forces have often opted for ADR or mediation as an element of the strategy used. This is a high-level vision that needs to be more concrete. Is ADR or mediation a way to resolve justice problems that need to be broadly applied by justice practitioners? If so, how can this be developed in an evidence-based way? Alternatively, are private sector arbitrators and mediators the preferred actors responsible for service delivery? If so, will they be able to reach 80% or more of the target group?

Strengthening community justice services is another popular strategy for task forces. HiiL has worked with task forces focused on holistic approaches to family justice or on the justice needs of rural populations in post-conflict countries. Previous task forces that have addressed land disputes have looked at improving registration of land ownership. Committees tasked with redress for systemic injustices have developed criteria for victim compensation.

The hypotheses embodied in the strategies need to be tested during the programming phase. Before a task force definitively selects a game-changing service, the stakeholders need to assess the feasibility of its implementation. Is the strategy likely to achieve the goal and move the indicator forward? Are there organisations ready to deliver it? Is the financial model sound?

View Additional Information

- HiiL has developed a method on developing pathways to meet specific justice goals that have been agreed upon by a group of committed justice leaders. These pathways are flexible and can be adapted to fit varying contexts and goals.

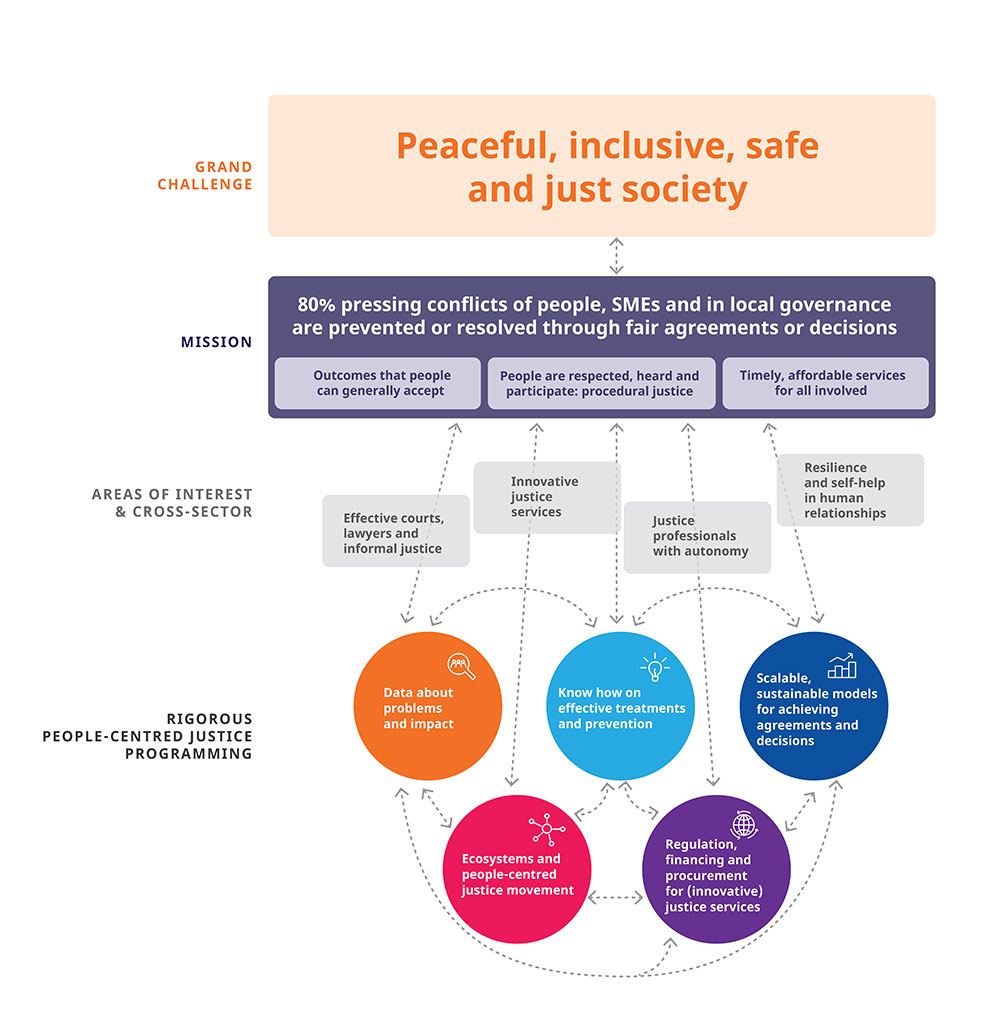

A mission approach example

In the flowchart below, a so-called mission map is sketched. It represents the five strategies outlined in Chapters 4 to 8 of this report. Data collection on problems and outcomes is combined with developing evidence-based treatments for the selected justice problems, which could be work conflicts, land use issues, domestic violence or the most common types of property crime. How to inform people, how to give them voice, how to involve them in designing solutions for the issues, and how to establish fair monetary contributions; at each step, the most effective interventions will be designed and continuously improved during implementation. Treatments will then need to be delivered in all situations by using the most effective service delivery models, which could include community justice services, online-supported one-stop procedures, or user-friendly contracts. An enabling regulatory environment that supports continuous R&D will drive this process, fuelled by practitioners, an ecosystem of innovators, and more vocal users. This open environment, supported by a stronger evidence base on what works and more sustainable delivery models, will rapidly make providers of justice services and justice practitioners more effective. New services can emerge and self-helpers will become more confident. Outcomes that people can generally accept will be clarified and will be more frequently the endpoints of more effective treatments that will also deliver on the most prominent procedural justice needs. The improved service delivery models ensure that solutions will be accessible for everyone against reasonable, foreseeable costs. Instead of being overburdened and under-resourced, justice services become financially sustainable, serving far more people, achieving many more tangible results for their users and safeguarding new revenue streams.

A mission map such as the one above provides a theory of change for a programme. The outputs of the programme provide intermediate and more remote outcomes, ultimately leading to the measurable impact of resolved or prevented problems. Between each of the elements of the results chain, progress can be monitored and measured. Resources can be reallocated towards the nodes that are most promising. Bottlenecks can be targeted.

Justice innovation traps: learning from experience

Learning from failure is crucial. HiiL has worked with a number of task forces over the past ten years. Hundreds of innovators have come to us with their ideas and initiatives. We have taken leaps of faith ourselves and have made every imaginable innovation mistake. The failures in justice innovation and court pilots are as instructive as are the successes. Here we share four points that we suggest future innovators avoid, as they can lead to costly delays and wasted energy.

Piloting without sustainable revenues in sight:

Piloting without sustainable revenues in sight: A recurring mistake is to start pilots but postpone thinking about revenues and rewards. Doing justice equals doing good, so innovators often assume that somebody will pick up the bill. Early on, this may be the case, and the task force may be misled by this. Many NGOs love justice innovation and are happy to spend significant sums on a pilot that protects the rights of women or children, for example. Politicians love free mediation centres. Big law firms love pro bono programmes. Prosecutors love programmes that divert cases from courts and bring multi-disciplinary teams into the room to decide on the best treatments. Judges pilot a lot.

The question a task force should ask about any pilot is: is this financially sustainable as a scaled venture? If the pilot is akin to building a fancy school in Tanzania to fix the national education system, or flying doctors to remote places to improve community health services where local networks of providers already exist, it should be reconsidered.

People love to spend money on something tangible. Some innovators repeatedly secure grants and awards. But grants seldom work in the long-run. Effective justice services need a sustainable stream of revenues that exceed costs. This way, justice practitioners can be rewarded for their efforts, money can be saved, and the service can be scaled and continuously improved. There are no shortcuts. The consequences of this are discussed in Chapter 6.

Fixing services that do not yet deliver fair outcomes:

Innovative lawyers often propose improvements to current processes; for example, tools to increase the number of productive hours at law firms, or referral sites that match lawyers and clients. Courts try hard to decrease their backlogs, refer cases to mediation, or spend millions to digitise their files and procedures.

More of the same: what is the effect on resolution rates of these measures often considered by reformers?

- Better planning of court cases

- Greater integration of courts, police and prosecution

- Programmes to reduce backlogs

- Court appearance reminders

- Diversion of cases to mediators

- Pro bono services provided by major commercial law firms

- Limited time for lawyers to argue their cases

- Anti-corruption measures

- Laws written in user-friendly language

- Improved processes for updating laws

The task force is likely to receive many suggestions to first upgrade current processes and services (UNODC and UNDP 2016; Law Commission of India; Republic of Kenya 2012). More digitisation, better access to court houses, improved scheduling of court hearings, or limits to the number of pages in documents filed – these can seem like effective upgrades. Many countries launch huge projects to update their codes of criminal and civil procedures. Judges and lawyers typically have many ideas on how to improve services provided by the courts. Expanding legal aid by lawyers has broad support. Alternatively, task force members may want to build on trends in investments in legal tech and in the allocation of court resources. In our 2020 trend report, Charging for Justice, we found that most investments go to startups that increase the efficiency of law firms or legal departments of major businesses. We also described the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on upgrading court IT. We estimated that only 2.5% of investments in legal tech go to services that target individual customers with legal needs.

It is tempting to believe that these proposed improvements will ultimately lead to better outcomes for people with justice problems. Task force members should be invited to test their assumptions by sketching how this trickle-down mechanism would work in practice. A task force should investigate whether such a mechanism is realistic, and whether working on these improvements is the best way to spend precious time and money.

Will resolution rates be increased? Will people get substantially better outcomes? What impact will they have in a typical justice journey? The task force can use the criteria in the box below to assess the proposed upgrades.

USING INDICATORS TO ASSESS PROPOSED UPGRADES

Description of upgrade | Example: Improved enforcement of court judgments with monetary sanctions. This happens through (1) investing in a network of debt collectors, (2) improved ways to collect debts from employers and banks and (3) improved ways to sell debtor’s assets |

|---|---|

Assessment criteria: | Example of assessment |

|---|---|

What is the expected increase in resolution rates for the most pressing justice problems?

| Four percent of pressing problems are decided by the courts. In 25% of cases involving a pressing family, land or crime problem, money payment is an essential component of resolution 70% -> 85% compliance = 0.3%

Is thus the expected increase in resolution rates

|

Which people (with high impact justice problems) will benefit from this upgrade?

| Mostly companies collecting debts and governments collecting fines. A small number of individuals who have personal injury cases or who collect child support or unpaid wages via a court procedure will also benefit.

|

How many pressing injustices will be prevented per year?

| Evidence for court sanctions and effective enforcement preventing injustice is inconclusive.

|

What is the investment needed for this upgrade?

|

Programme of several millions of euros

|

What are the yearly costs of sustaining this upgrade?

|

The cost of maintaining the network minus the debt collection fees that can be collected from debtors and creditors.

|

What are possible negative side effects and how can they be avoided?

| Increased debts for indebted persons, which can be avoided by better debt restructuring

|

How likely is the programme to be successful in implementing the proposed interventions?

| Estimated 60%.

|

What are the best alternative ways to invest this amount in people-centred justice and allocate an annual budget for this?

|

Calculate the investment and annual costs. Compare with alternative ways of investing/spending this amount.

|

Another tool to let task force members reflect on upgrades is to conduct studies visualising current justice journeys, such as those conducted by RMIT University (2016). These visuals often reveal that people need to interact with a range of professionals and agencies to address their problem. A victim of an accident may have to deal with the police, medical experts, insurance companies, lawyers, social security agencies, the prosecution, a mediator and a court. Each of these actors has different bureaucratic procedures that come with many formalities.

Mapping current justice journeys will help the task force and providers of future gamechangers strengthen the case for more fundamental renewal. It will also make it easier to identify the crucial elements of treatments. Many task forces indeed consider replacing existing services. Stakeholders they consult want to introduce alternative dispute resolution methods or renew the connection between formal and informal justice in their countries. They want to set up new types of specialised courts. They suggest diverting cases from the criminal justice system to new justice services. They recommend investing in legal information provision as an alternative to letting each person be informed by a lawyer. More often than not, task forces agree to replace existing services with alternatives or cautiously integrate newly-designed services into the existing justice system.

Missing the submission problem:

Many legal innovators look at court procedures and assume they can do better. They design smart arbitration procedures, delivering decisions in two months. Others start offering online mediation services with highly skilled mediators. Many lawyers have mobilised their IT-savvy friends to design algorithms for settling monetary claims in a rational way. Judges, too, often reflect on possible improvements to their work processes – In pilot projects in the Netherlands and Belgium, judges have developed procedures that allow claimants to walk in with a problem and tell their story, upon which the judge will invite the other party for a dialogue. In most countries, some judges have tried to design more sophisticated procedures to deal with construction conflicts or personal injury.

The first question that these legal innovators should be asked is: how will you ensure that the parties submit to your new process? The usual answer from innovators is that the parties will love the procedure and prefer it to the unpleasant experience of the procedure currently offered.

This is not how things work. The graveyard of justice innovation houses many seemingly smart procedures that have been offered as a voluntary option. The stumbling block is that new ways of resolving disputes have to be sold to all parties to a conflict. A conflict is by definition a situation where people do not agree on the way forward. Most of the time, one party needs a solution more urgently than the other. Solutions that claim to benefit only one of the parties are unreliable because it is difficult to understand the nature of the problem by looking only at it from one side.

Effective dispute systems are likely to be “mandatory.” From a people-centred perspective, this means that they contain incentives for both parties to participate, even if the process is difficult or the outcome may be discomforting. So strategies to develop game-changing services involving a third party start by fixing this submission problem, which may be quite a challenge.

Inability to remove legal hats and take other expertise onboard:

Many reform attempts suffer from an excessively or exclusively legal lens. Solutions are suggested in the form of new laws, additional information about laws or additional legal services. The reality of justice reform is that many other skills and resources are needed. These cannot be gathered from IT experts or managers alone – they need to be integrated into better resolution processes and service delivery models. To generate impact, justice innovators must consider a wide range of perspectives and be prepared to wear many hats: that of a creative designer, a policy maker, a user, and a donor or investor. The prospect of becoming a justice entrepreneur overnight by creating a solution to fix the justice system is exciting to many young lawyers and judges. But to make a real difference, innovators must be prepared to work with other stakeholders who may have conflicting interests. This is challenging but essential work. Working collaboratively rather than in silos can help innovators avoid introducing solutions that are certain to fail.

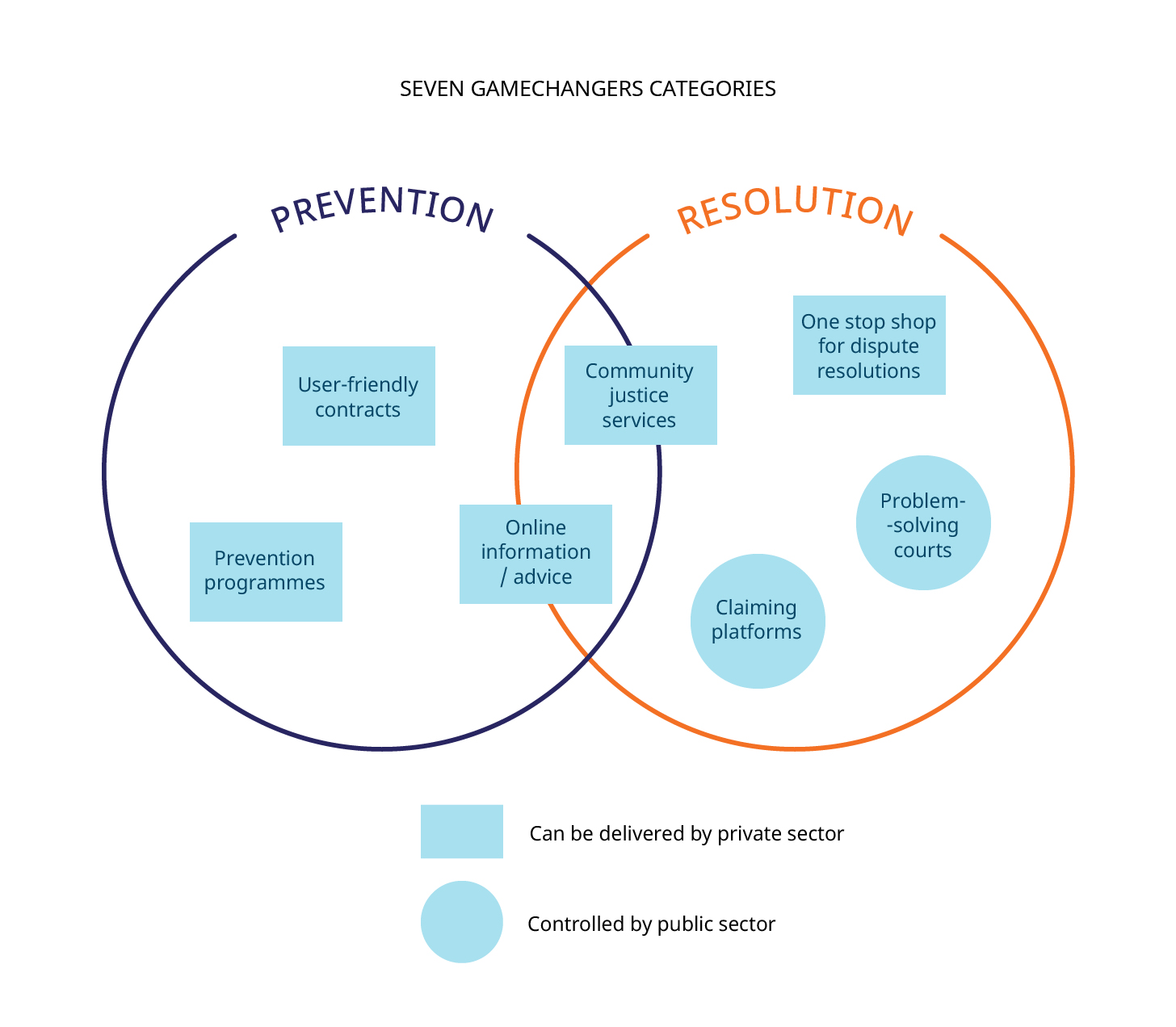

Selecting promising service delivery models: seven potential gamechangers

After deciding which pressing justice problems to select for implementing evidence-based practice, and testing early stage innovation suggestions, the task force will have to explore the possible service delivery models. Even when justice practitioners have the tools and methods to achieve high resolution rates in individual cases, these tools and methods will only improve the overall resolution rates in a country if they are available to every citizen, business and government agency. Currently, service delivery models are not scalable. Courts tend to be involved in around 5% of conflicts, and lawyers in perhaps 10-20% of cases. Government agencies have difficulties managing all conflicting interests regarding land use or delivering social services. Informal justice is irregularly provided in communities. Police and prosecution have limited capacity to deal with all kinds of of crime.

Based on lessons learnt, HiiL has developed three criteria to identify potentially game-changing service delivery models. A game changer must be a service delivery model that is: (1) able to deliver effective treatments consistently; (2) financially sustainable; and (3) scalable as a service (or as a combination of services) to 80, 90 or even 100% of the population experiencing the problem.

Based on these criteria, we suggest that task forces consider seven promising types of service delivery models. Other models are likely to exist and should be explored as well if found to be promising, but the seven models sketched below have a clear potential and are being pursued by many justice entrepreneurs.

Focusing on gamechangers will help innovators to design innovations that have the potential to deliver effective and sustainable justice services. The discussion will help policy makers to channel funds into viable innovations and formulate regulations in which these gamechangers can thrive.

Community justice services deliver solutions according to treatment guidelines effectively and to each person who needs them. Usually these services integrate formal and informal justice, and may take the form of: houses of justice; paralegals; justices of the peace; judicial facilitators; or community tribunals (HiiL n.d.-g).

Early stage examples of this game-changing service delivery model include justices of the peace, facilitadores judiciales and paralegal programmes in many countries, Casas de Justicia in Columbia, Local Council Courts in Uganda, and Abunzis in Rwanda. Case studies on Casas de Justicia and Local Council Courts can be found in the annex of this report. Bataka Court in Uganda shows how a private player can bring standardisation and regular monitoring and evaluation to a method of addressing disputes that is often considered informal and ad-hoc.

The Sierra Leone Legal Aid Board is another example of how community justice services developed at scale - through the participation of the public sector and donor agencies - brought down the unit cost of delivering justice. The tribal-state joint jurisdiction wellness courts in the United States effectively try to bridge the gap between formal and informal justice systems.

Community justice services exist in every type of country (low-, medium-, and high-income). They are more likely to exist in rural settings than in cities. Some are delivered by a panel of ordinary citizens, while others are overseen by individuals with authority in the community. Procedures are more likely to be standardised in high-income countries and more likely to be free-form in low-income countries (HiiL 2022a). Informal community justice has been incorporated by governments into organisations of judicial facilitators or by private initiatives into paralegal networks. Houses of justice and justices of the peace belong to the same family: the former as an interdisciplinary service facilitating resolution and the latter as an adjudication service with a simplified procedure.

The origin of the community justice service may limit its potential to scale. Sometimes community justice services are related to traditional justice within a tribe. In Ethiopia, different informal justice services cover different states, depending on which tribe has the majority. Community justice services may also have roots in a religion or be connected to a local or central government. In Switzerland, each canton has a separate system of local dispute settlement services. In some countries in the Sahel region of Africa, the government’s geographic reach is limited, meaning services initiated by the government may not achieve national scale. If a local tribe has developed a specific way of settling disputes, this may not be acceptable to people from other tribes in the same region. In Colombia, houses of justice are seen as mechanisms for establishing government authority in remote areas.

Community justice services sometimes scale across borders. Facilitadores judiciales programmes exist in several South American countries, and paralegal models can be found in many African countries (HiiL 2022a).

HiiL’s (2022a) policy brief on Community Justice Services outlines the reasons why we expect this gamechanger category to grow and the barriers that community providers will have to overcome in order to achieve long-term sustainable growth. These include the following:

- 1. Standardising effective working methods in a setting of scarce resources

- 2. Monitoring outcomes

- 3. Combining the strengths of informal justice and rights-based dispute resolution

- 4. Making community justice services affordable and financially sustainable

- 5. Building scale from the ground up

Services that provide safe, certified and user-friendly contracts or other legal documents to people, ensuring fairness in families, at work, among neighbours, and between small businesses and their partners, as well as between governments and stakeholders in the use of land.

Creative Contracts in South Africa is a notable example of contract visualisation. While LegalZoom in the United States is an online information platform, it also provides easy to access contracts for everyday legal issues, especially those pertaining to SMEs. Platforms such as DIY Law in Nigeria, VakilSearch in India, and Avodocs in Ukraine are examples of successful document automation platforms that address the needs of small and medium enterprises.

Contracts and legal documents are needed to prevent conflicts or help manage them constructively. If user-friendly and effective, marriage, work and housing contracts can support fair and effective relationships between people. A major mining, energy or housing development project can only be successful if it is based on consent from the community, including groups that benefit from it and those who have to cope with adverse consequences.

User-friendly contracts can be implemented in a variety of settings. Well-balanced marriage contracts are more likely to be successful in settings where it is already customary or legally required to have a formal marital agreement. Laws on taxes may make it more (or less) likely that an employment or rental contract will be set in a formal document (HiiL n.d.-h).

Visual contracts may be needed more in settings where a significant portion of the population is illiterate. That said, many people – regardless of their literacy – prefer visuals over texts. Along with visuals, user-friendly contracts also incorporate plain language and avoid unnecessary clauses when drafting contracts. So far, visual contracts have been used to draft employment contracts, informed consent forms for medical procedures, and non-disclosure agreements. A combination of visual, plain language and simplified contracts have been developed for procurement contracts, sales contracts by General Electric in the United States and not-for-profit organisations like World Commerce and Contracting in the United Kingdom (HiiL 2022b). The potential for innovation in contracting is vast, particularly for long-term relationships, where regular evaluation and updating can be included in the service delivery model (Fenwich, Compagnucci and Haapio 2022).

In the policy brief on user-friendly contracts, we identify the critical success factors for organisations that provide user-friendly contracts involved in scaling and improving the quality of service delivery (HiiL 2022b). These include the following:

- 1. Optimising the user-experience

- 2. Showing and optimising the benefits for client companies

- 3. Changing the mindset of lawyers and companies on contracting

- 4. Developing a sustainable financial model

- 5. A supportive regulatory environment

One-Stop Shop Dispute Resolution

Tribunals or platforms offer one-stop dispute resolution services for employment, family or other justice problems by connecting advice, negotiation, facilitation and adjudication in a seamless way. These services tend to be offered on multi-channels, that include online, telephone, chat-based and complimenting in-person services. They need to be mandatory for the defendant, or have another solution for the submission problem, in order to be effective and scalable (HiiL n.d.-i).

Tribunals and online platforms offering one-stop dispute resolution are part of the next generation of civil justice. They build on a major trend towards supplying ADR and mediation services in connection with adjudication. Examples of One Stop Shop Dispute Resolution include Civil Resolution Tribunal in Canada, Uitelkaar.nl in the Netherlands and SAMA in India. Online dispute resolution modules are now often operated by individual courts in the United States and elsewhere, with functionalities ranging from online filing to online mediation or online negotiation support.

One-stop shop procedures that integrate information, negotiation, mediation and adjudication support are mostly found in high-income countries. Ombudsman procedures also may include facilitation and adjudication in the form of (binding) recommendations (Wikipedia 2022). These are most commonly found in higher-income countries and their task is usually limited to the relationship of citizens with government agencies. In some countries, this ombudsman model is also applied to consumer complaints. England and Australia have numerous ombuds services for a range of consumer products.

If the government in a particular country has already developed a one-stop shop procedure for a different purpose (for example, for licences needed by companies), a one-stop shop procedure in courts is probably more likely to be accepted. In Islamic countries, the Qadi culture – where mediation and adjudication are more integrated and procedures do not assume representation by a lawyer – can be helpful as well.

In a policy brief, we identify the critical success factors for scaling One-Stop Shop Dispute Resolution Mechanisms, focusing on how public-private partnerships, outcome monitoring and specialisation can strengthen the case for this gamechanger category (HiiL 2022c). The success factors also include some of the following:

- 1. User-centred design of the specialised, one stop process

- 2. Solving the ‘Submission Problem’: Getting the other party to the table

- 3. Monitoring outcomes

- 4. Form effective public-private partnerships

- 5. Government stimulating initiatives: opening the regulatory doors

- 6. Sustainable revenue model

Problem-solving practices or courts that bring defendants, victims, lawyers, public defenders, community leaders and prosecutors together to effectively address criminal behaviour. Key features of a problem-solving treatment include rehabilitation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and accountability that have to be delivered to many people (HiiL n.d.-j).

Problem-solving courts are a collaborative criminal justice innovation focused on individualised treatment and accountability. We examples of this gamechanger category in the United States in the form of Mental Health Courts and Drug Courts. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa is another prominent example of bringing rehabilitation and restoration into focus in addressing criminal disputes.

Problem solving criminal justice services operate with the understanding that punishment is a limited, and not always effective, response to harmful behaviour. Victims, perpetrators and the communities in which they live need more than a guilty verdict with a fine or a prison sentence.

Problem-solving courts, dealing with common types of crime, have mostly been established in high-income countries such as the United States and Australia. Therapeutic justice and restorative practices on which problem-solving courts are based are used in different parts of the world, but the extent to which they are used largely depends on the approach of the judicial officers in power. In low-income countries, community justice services may deliver informal justice in a way that resembles the solutions delivered by the problem-solving courts.

Claiming services help people access vital public services quickly and at low cost. This delivery model is appropriate for social security benefits, proof of personal identity, healthcare benefits and similar outcomes. These services are supported online, combined with help desks or local in-person assistance (HiiL n.d.-k).

Online supported claiming has been finding traction in many countries. While many platforms focus on minor issues such as seeking compensation for defective consumer goods or compensation for flight delays, others focus on more serious issues. Examples include Haqdarshak in India, which provides access to government benefits to people living in rural areas through a combination of an online platform and local assistance, and JustFix.nyc in the United States which works on tenant rights.

Such claiming platforms empower citizens who need vital (government) services. Claiming platforms help people to navigate bureaucratic procedures and thus make services more equally accessible. Their effectiveness depends on the maturity of the public administration and judiciary in a given country. Services that provide access to digital identity such as iVerify in Nigeria and Peleza in Kenya have proven to be particularly useful in lower-income countries. In the United States, Turbotax is a private service that helps people file their tax returns. In other countries, the government has set up user-friendly tax filing portals. The more public services are effectively delivered by the state, the less claiming platforms are needed.

Claiming in high-income countries is now mostly supported online, matching high levels of access to the internet. In India, a sophisticated virtual platform — Haqdarshaq — is being taken door-to-door by local agents at the village level. Hybrid services are sometimes also needed for vulnerable groups in high-income countries (including migrants and illiterate or differently abled people). As part of these hybrid services, social workers and legal aid lawyers can deliver help offline.

Prevention programmes or services that are supported by apps to ensure safety and security from violence, theft and fraud (HiiL n.d.-l).

Prevention programmes can take many different forms, from awareness campaigns, to programmes geared to legal empowerment, or to tools that can aid prevention or escalation of a legal issue. Yunga in Uganda and Ushahidi in Kenya are examples of programmes that help prevent legal disputes through the use of different technologies.

Prevention of theft and violence is becoming more widespread with the introduction of low-tech devices. WhatsApp groups and more sophisticated neighbourhood watch apps exist in different parts of the world. These programmes rely on neighbours coming together. Prevention programmes also rely on co-creating protection with the law enforcement agencies that will be alarmed or informed so they can take further action.

Online information and advice and follow-up services

People-centred online information and advice and follow-up services that help people solve justice problems in a step-by-step, fair and effective way that is consistent with their legal entitlements (HiiL n.d.-m).

Examples of this gamechanger category are many and are found in many countries. However, those that provide a clear value proposition to users beyond the provision of information are few. A2J Author in the United States and Mero Adhikar in Nepal can be considered good illustrations of step-by-step and clear follow-up services that can be integrated into online information platforms, aiding progress towards scale and sustainability.

Online information and advice services tend to be run by law firms, individuals, startups, non-profit organisations, or sometimes even the government as in the case of the website of Citizens Advice in the United Kingdom. These services are a helpful starting point in an individual’s justice journey. As we will see in later sections, however, web portals and mobile apps need substantial investment to become effective self-help guides that lead to higher rates of resolution. Successful examples of these are still rare, even in high-income countries.

If evidence-based treatments and game-changing services are indeed needed, rigorous programming demands that the task force goes beyond incremental change. The following chapters show how a task force can lead strategically.

View References

Fenwick, M., Corrales Compagnucci, M., & Haapio, H. (2022). Research Handbook on Contract Design. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Hendley, K. (2017). The Unsung Heroes of the Russian Judicial System: The-Justice-of-the- Peace Courts. The Journal of Eurasian Law, Duke University.

HiiL, (2020). Charging for justice: SDG 16.3 Trend Report 2020.

HiiL, (2022a). Policy brief: Community justice services. HiiL.

HiiL, (2022b). Policy brief: User-friendly Contracts. HiiL.

HiiL, (2022c). Policy brief: One-stop shop dispute resolution. HiiL.

HiiL, (n.d.-g). Community justice services. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/the-gamechangers/community-justice-services/. Accessed on July 31, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-h). User-friendly contracts. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/the-gamechangers/user-friendly-contracts-and-other-legal-documents/. Accessed on July 31, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-i). Online information, advice and representation. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/the-gamechangers/online-information-advice-and-representation/. Accessed on July 31, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-j). Problem-solving courts. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/problem-solving-courts-for-criminal-cases/. Accessed on July 31, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-k). Claiming services helping people to access vital public services. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/claiming-services-helping-people-to-access-vital-public-services/. Accessed on July 31, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-l). Prevention programmes or services. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/claiming-services-helping-people-to-access-vital-public-services/. Accessed on July 31, 2022.

HiiL, (n.d.-m). Online information, advice and representation. URL: https://dashboard.hiil.org/the-gamechangers/online-information-advice-and-representation/. Accessed on July 21, 2022.

Huge Domains, (n.d.). Legalfacile.com. URL: https://www.hugedomains.com/domain_profile.cfm?d=legalfacile.com. Accessed on July 27, 2022.

Law Commission of India, (2017). Assessment of statutory frameworks of tribunals of India: Report number 272. Government of India.

Ombudsman, (2022). Wikipedia. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ombudsman. Accessed on August 1, 2022.

Republic of Kenya, (2012). Judiciary transformation framework.

RMIT University, (2016). Pathways towards accountability: Mapping the journey of perpetrators of family violence- Phase 1.

UNODC and UNDP, (2016). Global study on legal aid: Global report

Table of Contents