Delivering Justice, Rigorously

This report presents an evidence-based, people-centred approach to the delivery of justice. It aims to inform the work of a growing group of leaders who are responding systematically to the demand for fair, effective procedures that address populations’ dispute resolution needs.

Case Study: The Justice Dialogue

Case study The Justice Dialogue Key takeaways Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / Case Study: The Justice Dialogue Author: Kanan Dhru, Justice Innovation Advisor Introduction The HiiL virtual Justice Dialogue took place on Wednesday, 20th April 2022 from 09:00hrs-13:00hrs CEST. High-level participants from Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, the Netherlands and USA participated in this Dialogue, […]

5. Strategy 2: Scaling gamechanging justice services

5 5. Strategy 2: Scaling gamechanging justice services Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / 5. Strengthening gamechangers: main points Before explaining in Chapter 6 how potential gamechangers can be turned into an investable opportunity, we indicate the main points of attention for each gamechanger. What do they need to scale effective services in a […]

Authors

Authors Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / Authors Authors Prof Dr. Maurits Barendrecht, Director Research & Development Isabella Banks, Justice Sector Advisor Juan Carlos Botero, Justice Sector Advisor Manasi Nikam, Knowledge Management Officer Kanan Dhru, Justice Innovation Researcher About HiiL HiiL (The Hague Institute for Innovation of Law) is a social enterprise devoted to […]

Methodology

Methodology Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / Methodology HiiL specialises in rigorous programming for people-centred justice. Our mission is in line with the magnitude of this challenge: prevent or resolve 150 million pressing justice problems by 2030. We believe that data on what works, combined with innovation, can transform the justice sector. Towards more […]

Case Study: CrimeSync

Case study CrimeSync Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / Case Study: CrimeSync Author: Kanan Dhru, Justice Innovation Researcher CrimeSync exemplifies the individual grit and determination in attempting to change the domain of justice delivery. CrimeSync is the brainchild of Sorieba Daffae, a young lawyer and changemaker navigating the complexities of criminal justice institutions in […]

Case Study: LegalZoom

Case study LegalZoom in the US Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / Case Study: LegalZoom in the US Author: Manasi Nikam, Knowledge Management Officer Introduction The traditional justice system often fails to meet the everyday legal needs of people. To bridge this gap, the people-centred justice movement emphasises on delivering outcomes that people want […]

Case Study: Local Council Courts in Uganda

Case study Local Council Courts in Uganda Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / Case Study: Local Council Courts in Uganda Author: Manasi Nikam, Knowledge Management Officer Introduction During the guerilla war that took place in the National Resistance Movement (NRM) of 1981-86, Resistance Councils were established to mobilise people as well as resolve disputes […]

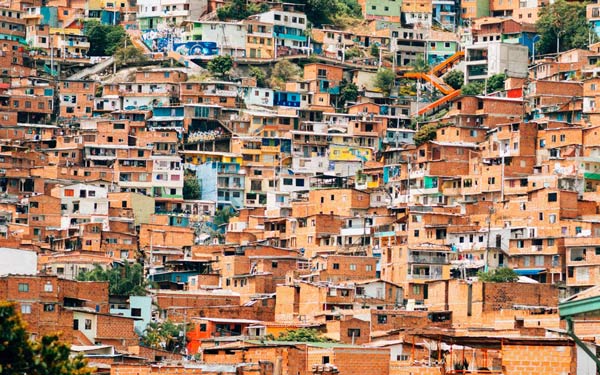

Case Study: Casa De Justicia in Colombia

Case study “Casas de Justicia” in Colombia Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / Case Study: Casas De Justicia Colombia Author: Juan Botero, Justice Sector Advisor Out of every 1000 disputes that arise in Colombia today, how many of them are peacefully resolved through institutional dispute resolution channels and how many lead to a downward […]

Case Study: Problem-Solving Courts in the US

Case study Problem-Solving Courts in the US Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / Case Study: Problem-Solving Courts in the US Author: Isabella Banks, Justice Sector Advisor Introduction Problem-solving courts are specialised courts that aim to treat the problems that underlie and contribute to certain kinds of crime (Wright, no date). “Generally, a problem-solving court […]